The unexpectedly dark underside of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel

Has the show always been this grim?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The fourth season of Amazon's The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel arrives Friday as a kind of postcard from our recent past. The last time we saw Midge was in December 2019, when the show's third season dropped in its entirety; Maisel's return in 2022 raises the inevitable question of whether its joke-a-second, madcap reverie can still be a welcome diversion, or if it'll be a difficult reminder of the gone world.

But while Amy Sherman-Palladino's critically-acclaimed confection had long walked the fine line between being either an irresistible fable about the unlikely rise of a Joan Rivers-like comic in 1950s New York, or a saccharine homage to an imagined past, both sides of the debate may have it slightly wrong. As the fourth season begins to suss out, it's possible Maisel has always been just a little bit darker than its enthusiasts and detractors imagined.

When we last saw Miriam "Midge" Maisel (Rachel Brosnahan), she'd just been left on the tarmac by a Harry Belafonte-like musician named Shy Baldwin (LeRoy McClain) — for whom she had been serving as the opening act on a USO tour all season — over a particularly tactless set. Season four picks up right where it left off, with an outraged Midge tossing her clothes out the window of an airport cab she's sharing back to the city with her manager, Susie Myerson (Alex Borstein). It's not just losing the opportunity she's spent three seasons doggedly pursuing that has her worked up — she now has to go tell the father of her ex, Joel, that the collateral she put up to borrow money from him for her lavish apartment has vaporized, setting off a chain reaction of IOUs.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Interestingly, the first episode leans into one of the show's biggest puzzles: Who is watching Ethan and Esther, Midge and Joel's nearly-always-offscreen children? While Sherman-Palladino has previously batted away disapproval of Midge being a "terrible mom" — "I have no patience for that s--t whatsoever," she told The Hollywood Reporter of such criticisms — season four almost seems to lean into the condemnations. For example, when Midge slinks home, she calls her parents and pretends to be in Prague but finds out that they are in the midst of throwing a birthday party for Ethan. She later meets them at the Coney Island amusement park, where she finally confesses that she's been fired by Baldwin. As far as I can tell, she doesn't greet her son in the scene.

A few years ago, Vox's E.J. Dickinson asked openly, "Where are The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel's children?" The answer seems to be that they are more or less constantly in the care of their grandparents. Sherman-Palladino has confirmed as much: "These kids have two sets of grandparents who dote on them, and they have a father that's there all the time," she went on to the Reporter. But Joel opened a nightclub atop an illicit Chinese gambling hall in season three, and while he's at the Coney Island romp for Ethan, he also does not appear to play a meaningful role in his kids' lives. Of course, in a material sense, these wealthy Manhattan cherubs will be fine, but the sense that no one — including their exasperated grandparents — particularly cares about them is an emotional weight that harshes the show's vibe, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

While Midge's absent parenting has been a source of amusement (or scorn) in the past, it now falls cleanly into a trend of recent "women who leave their kids" films and shows, including The Lost Daughter and HBO's remix of Scenes From a Marriage. As Amanda Hess wrote for The New York Times, "When a man leaves in this way, he is unexceptional. When a woman does it, she becomes a monster, or perhaps an antiheroine riding out a dark maternal fantasy." Midge's children, of course, are not literally abandoned (as Sherman-Palladino is more than happy to point out), but she also can't pursue her dream of becoming the Queen of Comedy without offloading the 24/7 childcare expected of women in the 1950s onto someone else. And it's a testament to Brosnahan's magnetism that most audiences don't even register her absentee parenting as anything but plucky.

Maybe it's because nearly two years into a seemingly interminable pandemic, comfort TV just isn't hitting like it used to, but in the two episodes made available for critics, Maisel now feels claustrophobic, confined, and unexpectedly dark and sad, adding a texture to the show that it didn't have before. Historically, Maisel has taken flak for being too sweet; The New Yorker's Emily Nussbaum memorably called it "treacly and exhausting" in 2018. "The show is downright Sorkinian in its emphasis on Midge's superiority," Nussbaum added.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is it though? Because in season four, it seems obvious that Midge is unapologetically self-involved, burning through relationships and friendships and her family's financial capital, and she consistently dives headlong into professional ruin — all without seeming to understand that she's taking the nearly-destitute Susie down with her. Just because she's challenging rigid gender hierarchies that have been at least somewhat upended from the vantage point of the present doesn't mean that her choices don't have real consequences for the people in her life.

Midge has enough charisma to light up the Empire State Building, but she's equal parts heroine and antiheroine when you start to look closer. To be clear, it doesn't bother me that Midge pays no attention to her kids — it's not like we were all sitting around talking about Don Draper's half-assed parenting on Mad Men — but as a parent, it troubles me that no one in this supposedly rose-tinted universe really is. One of the show's subtle commentaries seems to be that Midge's parents and in-laws couldn't care less that she isn't fulfilling the era's expectations of perfect motherhood; what bothers them is that by becoming a public figure, she's advertising it for the world and inviting shame.

Hess describes the way that the maternal antiheroines of the moment "may leave, but they don't quite get away with it." They are haunted by their choices, ostracized, judged, cast out of polite society. And though doubt that's where Maisel is headed, it would certainly make it a more interesting show.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

February TV brings the debut of an adult animated series, the latest batch of ‘Bridgerton’ and the return of an aughts sitcom

February TV brings the debut of an adult animated series, the latest batch of ‘Bridgerton’ and the return of an aughts sitcomthe week recommends An animated lawyers show, a post-apocalyptic family reunion and a revival of a hospital comedy classic

-

The 8 best hospital dramas of all time

The 8 best hospital dramas of all timethe week recommends From wartime period pieces to of-the-moment procedurals, audiences never tire of watching doctors and nurses do their lifesaving thing

-

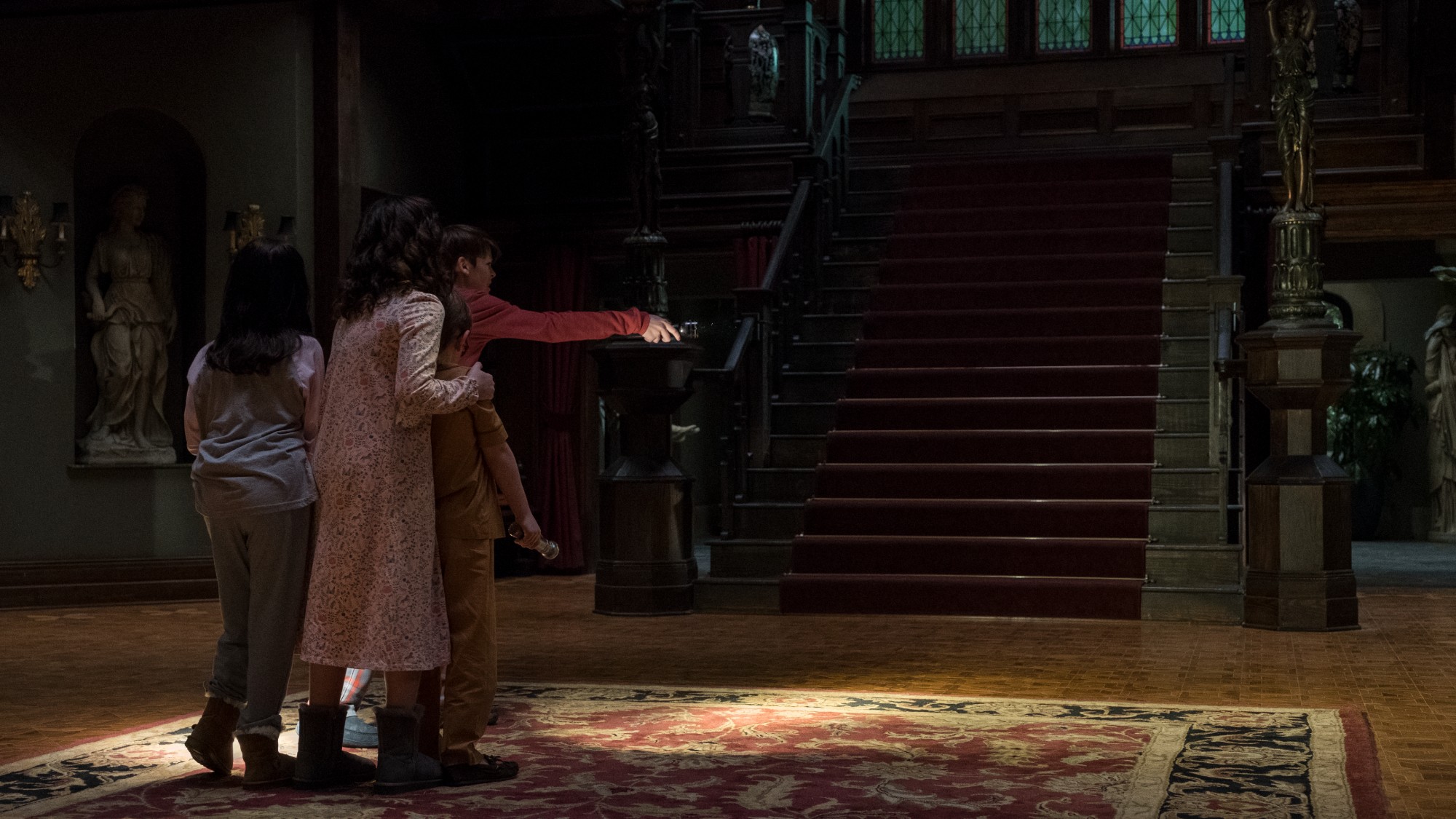

The 8 best horror series of all time

The 8 best horror series of all timethe week recommends Lost voyages, haunted houses and the best scares in television history

-

Scoundrels, spies and squires in January TV

Scoundrels, spies and squires in January TVthe week recommends This month’s new releases include ‘The Pitt,’ ‘Industry,’ ‘Ponies’ and ‘A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms’

-

The best drama TV series of 2025

The best drama TV series of 2025the week recommends From the horrors of death to the hive-mind apocalypse, TV is far from out of great ideas

-

The 8 best comedy series of 2025

The 8 best comedy series of 2025the week recommends From quarterlife crises to Hollywood satires, these were the funniest shows of 2025

-

A postapocalyptic trip to Sin City, a peek inside Taylor Swift’s ‘Eras’ tour, and an explicit hockey romance in December TV

A postapocalyptic trip to Sin City, a peek inside Taylor Swift’s ‘Eras’ tour, and an explicit hockey romance in December TVthe week recommends This month’s new television releases include ‘Fallout,’ ‘Taylor Swift: The End Of An Era’ and ‘Heated Rivalry’

-

Daddy Pig: an unlikely flashpoint in the gender wars

Daddy Pig: an unlikely flashpoint in the gender warsTalking Point David Gandy calls out Peppa Pig’s dad as an example of how TV portrays men as ‘useless’ fools