Why urban decline could be good — even for cities

How decentralization of wealth and status could make America more stable and resilient

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

These are hard times for America's big cities. Murder is up. Workers are staying at home rather than commuting. Fear that COVID-19 would be more virulent in urban environments proved unfounded, but the pandemic has cast a pall over dense conditions and communal leisure that are part of cities' appeal.

For skeptics of the urban revival that remade political economy in the 21st century, it's a moment of vindication. Writing in The American Mind, Joel Kotkin argues that the overlap between Americans' longstanding preference for a suburban lifestyle, the possibility of effective online collaboration, and "residual fear of proximity" spell the end of big cities' demographic, economic, and cultural dominance.

There's a certain perverse charm in Escape from New York fantasies of urban collapse, but we shouldn't celebrate urban problems. For one thing, cities produce a great deal of the country's wealth — at least partly because they offer opportunities that can't be found elsewhere. More importantly, over 10 percent of our population lives in big cities, and a much larger portion lives in extended metro areas. Their circumstances can't be neatly severed from those of an idyllic "real America."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

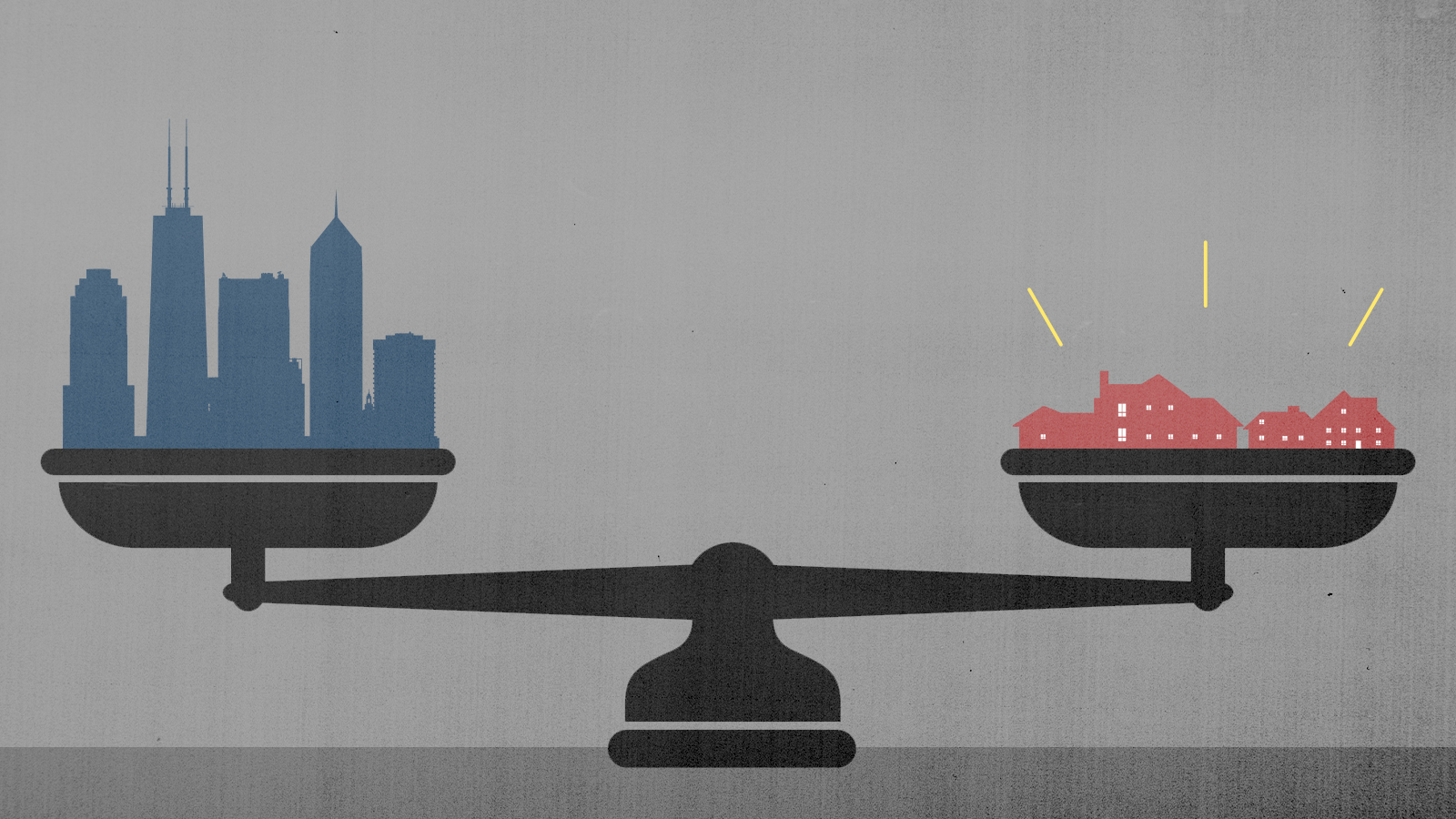

In the long term, though, the relative decline of big cities is a good thing. That's not because city life is inherently corrupting, an idea that extends back to Thomas Jefferson, or even because cities tend to be more progressive than suburban and rural areas. Rather, it's because the current close concentration of money, jobs, and social status is culturally stutifying and politically polarizing. Dispersal of those goods could make America more stable and resilient — and it could even make cities more interesting.

Kotkin has for decades been contending that big cities are overhyped and overrated, so there's a stopped-clock quality to his argument, and this type of prediction has been wrong before. The imminent decline of New York and its counterparts was widely forecast after the 9/11 attacks, for example, but that never happened. The situation likewise looks grim now, but a similar reversal of fortune is possible.

We also may be too sweeping in speaking of cities as an undifferentiated category. Postindustrial cities, like Baltimore, where the gains of the 2000s and 2010s were partial and tenuous, are in the worst shape. Yet despite the rise of work from home, some centers of the tech economy — like Seattle — continue to thrive. And the much-discussed decline of California shouldn't be confused with a shift away from cities per se. Last week, Tesla announced that it was moving its headquarters from the Bay Area to Austin, the country's fastest-growing major metro.

Population statistics can be misleading, too. Even if we distinguish between sunbelt boomtowns and the coasts, some of the recent losses in New York, San Francisco, and Boston were absorbed by their own metro areas. Identifying the city with just downtown, or even the formal jurisdisction, makes these shifts look bigger than they really are.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even movement between regions, finally, isn't necessarily a turn away from urban living. Some of the biggest winners in the past decade have been smaller cities that offer walkable neighborhoods and sophisticated amenities without the expense and hassle of Manhattan. That may be a rebuke to the idea of superdensity, which delights techno-futurists and horrifies populists. But it's perfectly compatible with an "inclusive urbanism" that recognizes traditional architecture and layout as genuine urban forms that lie in the vast middle ground between Hong Kong and a cul-de-sac.

Despite all these caveats, though, it's clear that something important is happening. The most striking change is the shift in the kind of high-wage, high-profile jobs that big cities once monopolized — along with their valuable spillover effects. Palm Beach probably won't replace Wall Street (neither did Stamford or other suburban outposts of the finance industry). But it seems likely to become a much closer adjunct.

That's bad for owners of downtown office blocks, but good for the country as a whole. The so-called "density divide" is a source of partisan polarization and embitterment. Suburban and rural Republicans feel imposed upon by the moral values and policy preferences of big cities, which shape the conversation even when they can't muster electoral majorities. Democrats, for their part, are frustrated that their huge advantage in the most populous cities and states doesn't translate directly into legislative or presidential victories.

As Kotkin points out, dispersion of population could help manage those tendencies. Ex-city dwellers will bring some of their liberal disposition with them, moderating former bastions of the right while growing the rural and suburban share of the electorate. A version of that effect is evident in states like Arizona and Georgia, which helped decide the 2020 presidential election.

Some conservatives worry that these and other places receiving urban refugees are being "colonized" by the left. It might feel that way in the short term, but in the long run there's reason to be optimistic. For one thing, there's a selection effect: People who truly disdain non-urban areas aren't likely to move there. Even if they don't necessarily lead to theoretical conservatism, moreover, homeownership and childbearing are both associated with Republican voting. Those options are more accessible outside urban centers, where ex-urbanites will be changed by their new surroundings just as they are themselves a source of change. Such shifts in life circumstances are more likely to move political preferences toward the center than will ideological hectoring.

The overall result, in other words, could be to reverse some of the geographic sorting that's made our politics so fraught. The positive results may not be evident by 2024, but urban recession reduces the threat of "national divorce."

Potential benefits aren't limited to politics, either. The concentration of cultural interest in just a few of the biggest or richest cities is intensely boring. This is a vast, bountiful, and maddening country. Our national variety of experience once generated an array of local and regional microcultures. Some of the most important movements, like Seattle grunge, Cleveland punk, and New Orleans rhythm and blues, were possible only because they were so distant from the centers of the entertainment industry.

The instant availability and universal circulation provided by the internet can flatten those differences. But the same technologies make it more possible for artists to live and work outside the few locations where they can hope to be discovered. At minimum, physical relocation might inspire new ideas and themes. The last thing we need is another novel about Brooklyn.

It would be tragic but perhaps justified if such gains came at the expense of cities. Yet these changes can be an opportunity for cities, too. The social model exemplified by New York City — in which a small number of high earners ensconced in carefully burnished neighborhoods effectively subsidized a vast underclass — brought cities a needed measure of stability and glamor after the long decline of the 1960s through the 1990s. But it became a gilded cage that cultivated finance, tech, and tourism at the expense of middle-class opportunities.

If their leaders are smart, cities will respond to the erosion of that model by recalling its origins. The revival of New York City can be traced back to the development of bohemian colony in Soho, where artists took over spaces built for 19th-century industrial enterprises rendered obsolete by the economic and technological shifts of the period. Initially illegal, these loft conversions were eventually recognized and encouraged by authorities who saw them as a vehicle of economic development.

Today, the once-derelict neighborhood is home to some of the most expensive real estate in the world. Over in central business districts, meanwhile, commercial space is sitting unused as the white-collar employees whom it was intended to house work from home in their pajamas. There are legal and engineering challenges, but converting former offices could provide needed housing supply while bringing some life to neighborhoods that represent the worst of American cities.

Like its predecessor, the next urban revival may happen where it's least expected.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’