How livestock grazing is preventing the return of rainforests to the UK and Ireland

Most of the UK and Ireland’s grass-fed cows and sheep are on land that might otherwise be temperate rainforest

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

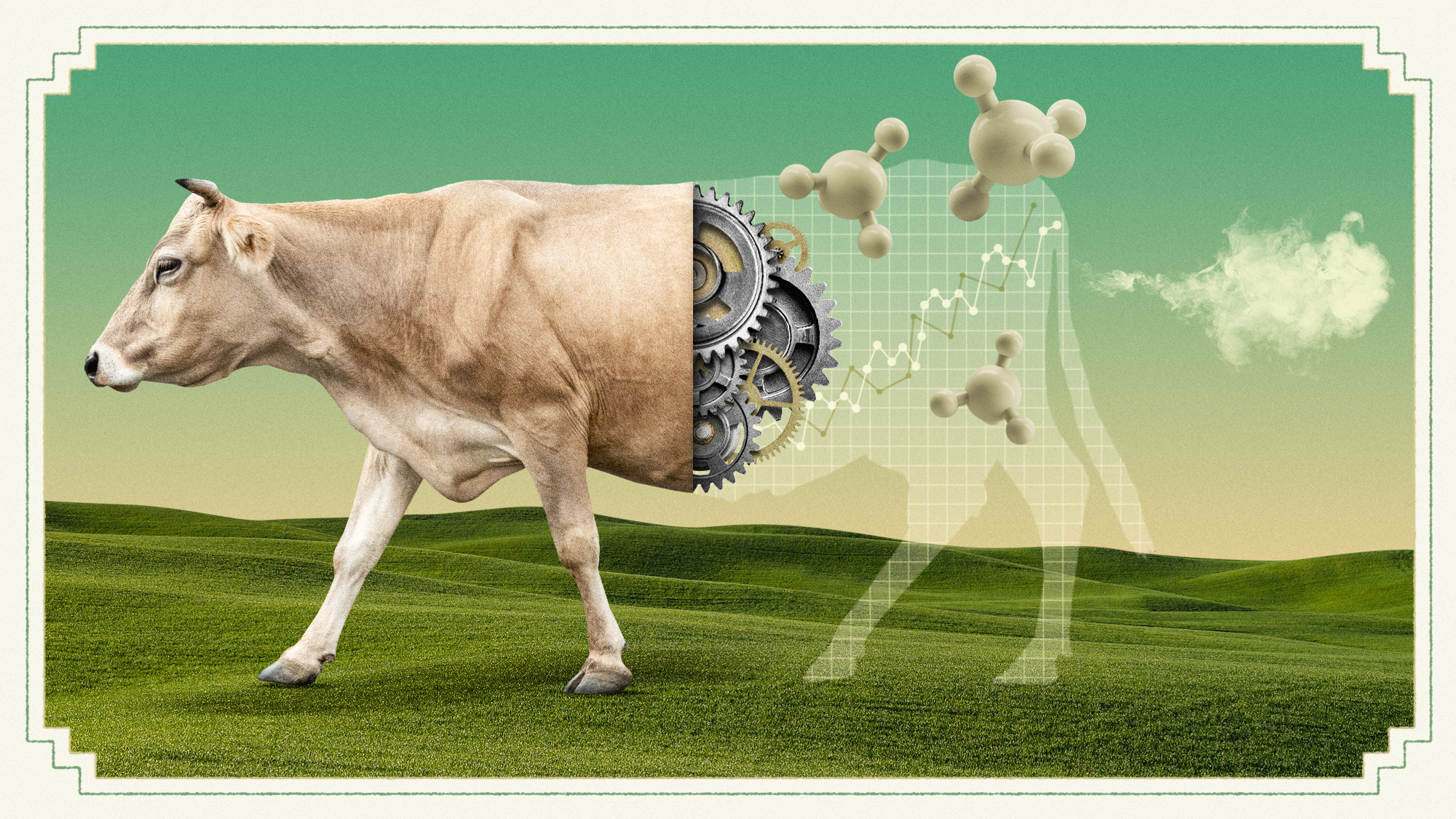

Emma Garnett, a researcher in the health behaviours team at the University of Oxford explains how while people are increasingly aware of the climate impact of meat, there is still less discussion about its large land footprint and how that harms nature and biodiversity.

A few years back, the president of the National Farmers’ Union of England and Wales wrote a defence of the meat industry after a BBC documentary criticised its environmental impact. “British farmers do not clear rainforest to make way for beef and lamb production,” she wrote. “British meat does not come from the ashes of the Amazon.”

Many believe this but unfortunately it isn’t quite true. For one thing, livestock production in the UK and Ireland is still linked to rainforests abroad since chickens, pigs and cows are often fed imported soybeans. Brazil is the world’s largest soybean exporter, and much of its crop is grown on deforested land.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Many people might also be surprised to learn that Ireland and western regions of Great Britain are home to rainforests: temperate forests sometimes called Celtic or Atlantic rainforests. And, like their tropical counterparts, UK and Irish rainforests are threatened by grazing livestock, particularly deer and sheep.

Fragmented forests

Only a tiny and fragmented area of UK and Irish rainforest remains. As the Woodland Trust reports, it “has suffered long-term declines through clearances, chronic overgrazing, and conversion to other uses”.

I’ve found in Twitter discussions that people will argue the treeless state of much of Britain’s National Parks is “natural”, but that’s not the case. When fences are put up and grazing is excluded, trees and vegetation quickly recover.

To protect nature we do need to minimise further deforestation. However, we also need to restore what we have lost. We’re used to viewing present-day tree clearing as deforestation, and we now need to view activities that prevent forests naturally regenerating as deforestation too.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Grazing livestock have huge land footprints

Most of the UK and Ireland’s grass-fed cows and sheep are on land that might otherwise be temperate rainforest – arable crops tend to prefer drier conditions. However, even if there were no livestock grazing in the rainforest zone – and these areas were threatened by other crops instead – livestock would still pose an indirect threat due to their huge land footprint. You need around 35 times more land to get 100g of protein from lamb than you do from peas, beans and other pulses.

Rainforest and livestock grazing are therefore competing for space. The UK and Ireland have some of the lowest forest cover in Europe at 13% and 11% respectively, and only one-tenth of this is natural rather than planted. Eating less meat and more plants means your diet has a smaller land footprint, which means more space for woods and rainforests to return.

Yes, grasslands in the British Isles with low levels of grazing can be important ecosystems for wildflowers and insects, but this is not what most grazing land is like. Grassland nature reserves managed for nature and not farming, such as Martin Down in Hampshire, have trees and shrubs – in the spring and summer the air is filled with birdsong and the ground with butterflies and orchids. They are a far cry from the intensively grazed fields and hillsides which resemble billiard tables and make up too much of the UK and Ireland’s grasslands.

Eating meat off well-managed nature reserves is arguably fine for nature and climate – but such tiny amounts are produced from these systems that meat consumption would have to plummet far beyond current reduction targets.

Furthermore, most British grass-fed cows are still fed crops on top of their staple grass. They typically have a larger arable land footprint per 100g than British legumes, and a massively larger footprint once you factor in their grazing land.

There is important on-farm biodiversity which needs to be supported, but this mustn’t be at the expense of conserving and restoring unfarmed ecosystems – which most (but not all) species prefer.

The UK and Ireland are some of the most nature-depleted countries in the world. And grazing is the most common land use – the vast majority of grass-fed livestock are harming not benefitting nature.

British and Irish rainforests are moving up the public consciousness thanks to campaigners such as Guy Shrubsole and Eoghan Daltun. People are increasingly aware of the climate impact of meat, but there is still less discussion about its large land footprint and how that harms nature and biodiversity. This will need to change if the world is to achieve recent commitments made at the biodiversity-focused COP15 summit to protect and restore nature.

Emma Garnett, Researcher in the Health Behaviours Team, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

Starmer vs the farmers: who will win?

Starmer vs the farmers: who will win?Today's Big Question As farmers and rural groups descend on Westminster to protest at tax changes, parallels have been drawn with the miners' strike 40 years ago

-

How 'corn sweat' has made summer in the Midwest worse

How 'corn sweat' has made summer in the Midwest worseUnder The Radar Lend an ear to this kernel of agricultural science.

-

Greece's deadly 'goat plague' threatens its trademark feta cheese

Greece's deadly 'goat plague' threatens its trademark feta cheeseUnder the Radar About 9,000 animals have already been culled amid outbreak of 'highly contagious' PPR virus

-

Why beaches are closing across the country

Why beaches are closing across the countryThe Explainer Step away from the water!

-

The growing thirst for camel milk

The growing thirst for camel milkUnder the radar Climate change and health-conscious consumers are pushing demand for nutrient-rich product – and the growth of industrialised farming

-

Why curbing methane emissions is tricky in fight against climate change

Why curbing methane emissions is tricky in fight against climate changeThe Explainer Tackling the second most significant contributor to global warming could have an immediate impact

-

How the EU undermines its climate goals with animal farming subsidies

How the EU undermines its climate goals with animal farming subsidiesUnder the radar Bloc's agricultural policy incentivises carbon-intensive animal farming over growing crops, despite aims to be carbon-neutral