Pros and cons of jury trials

Juries are a long-standing but much-debated element of the UK criminal justice system

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fewer jury trials could take place in the UK in an effort to try and ease the strain on an overburdened justice system that is near collapse.

The Crown Court caseload has reached "almost pre-pandemic levels", with the backlog so big that some cases could have to wait until 2029 to be heard, said Sky News.

The proposal to conduct fewer jury trials comes from an independent review of the criminal courts conducted by Brian Leveson, a retired senior judge, who said the current system was near "total collapse". Leveson has proposed the idea of judge-only trials for certain crimes, like fraud and bribery, as well as more out-of-court settlements to stop cases reaching court at all.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ministers will now consider the recommendations; however, critics will likely point to a dilution of the right to a trial by jury, while supporters will view pushing more cases to the Magistrates Court as a necessary easing of the burden on the Crown Court.

Here are some key arguments for and against trials by jury.

Pro: ensures representation

Having juries means that the "community is represented", with members of any "race, religion, gender and socio-economic group" brought together to "decide the fate of a fellow citizen", wrote Thomas Leonard Ross KC for The Sun.

Felicity Gerry KC, a professor of legal practice at Australia's Deakin University, agreed that in cases where the "public has a vested interest" and the verdict could result in a "life-changing punishment", it is "vital" that members of the community, rather than a lone "privileged professional", decides on the innocence or guilt of a fellow citizen.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jury service is "an exercise in democracy", Gerry added in article on The Conversation.

Con: jurors can be biased

Jury members are "subject to all kinds of societal biases that may prejudice their interpretation of the evidence", said Morgan in Glamour.

Finding out what goes on "inside the jury room" and "the biases that might influence jurors" is of vital importance, said psychologists Dr Itiel Dror of University College London and the Open University's Dr Lee John Curley and Dr James Munro.

Like all humans, jurors are "fallible beings" who may have biases that can lead to confirmation bias – when jury members distort the evidence "against their preferred verdict", or give "more weight to the evidence that favours their preference".

Bias in the criminal justice system is a "significant issue", the trio added, and can cause "miscarriages of justice", but establishing "procedures" can help to "avoid the potential for bias to influence the process".

Pro: boosts public confidence

Ditching the "anonymous balance" offered by a jury, said Scottish Criminal Bar Assocation president Tony Lenehan KC, in favour of the verdict of a "single middle-aged, university-educated person, most likely white and male", risks "attacks in the press for every decision the vocal minority dislikes".

The lone judges "will feel those eyes upon them", Lenehan wrote for The Times, and it would be a "strong character indeed who pays no heed". Allowing this "one interested party" to potentially have any sway in a case "robs" the justice system of "public confidence" and "essential transparency".

Responding to the Leveson proposals for judge-only trials, Matt Foot, the co-director of the charity Appeal, said trials without a jury would "increase the number of miscarriages of justice". Juries ensure "safeguarding" of the right to be "free from discrimination" and "confidence in our criminal courts".

Con: hung verdicts

Most juries are able to "reach their verdict unanimously", said Jacqui Horan, an associate professor of law at Australia's Monash University, on The Conversation. But in some cases, they "unable to agree" after deliberating "for several hours or days". This usually results in a retrial with a new jury.

The defence is "usually at an advantage" in retrials, according to The Sun, because the prosecution faces the "hard task of trying to surprise the defence team" with new evidence. By contrast, the defence can use their knowledge of the evidence presented at the first trial to "block all loopholes" and "amend what needs to be changed to build a stronger case".

Pro: checks on power

Scrapping juries would put "unprecedented power in the hands of judges", said Spiked's Luke Gittos, particularly in "complicated crimes" such as rape. Trials by jury are "inherently fairer" and are "an essential safeguard against injustice".

Juries can also be crucial in preventing "excessive state power", said lawyer Samantha Love in an article for the Oxford Royale Academy. They can help to prevent "laws being enforced with which the population do not agree", as well as ensuring that "society is involved in the administration of justice" and "protected from the state".

Con: expensive and time consuming

Although many argue that monetary cost should not be a "relevant factor" in determining the value of juries, "practicalities can be as important as principles", wrote Love for the Oxford Royale Academy. And the jury system does "have costs for the economy and the state".

Not only are jurors able to claim expenses for their travel and food during their jury service, they may also be absent from work "for sustained periods", potentially costing them and their employer. To have to "sit in court for two weeks without ever being called to sit on a case" is not "uncommon", Love added.

Richard Windsor is a freelance writer for The Week Digital. He began his journalism career writing about politics and sport while studying at the University of Southampton. He then worked across various football publications before specialising in cycling for almost nine years, covering major races including the Tour de France and interviewing some of the sport’s top riders. He led Cycling Weekly’s digital platforms as editor for seven of those years, helping to transform the publication into the UK’s largest cycling website. He now works as a freelance writer, editor and consultant.

-

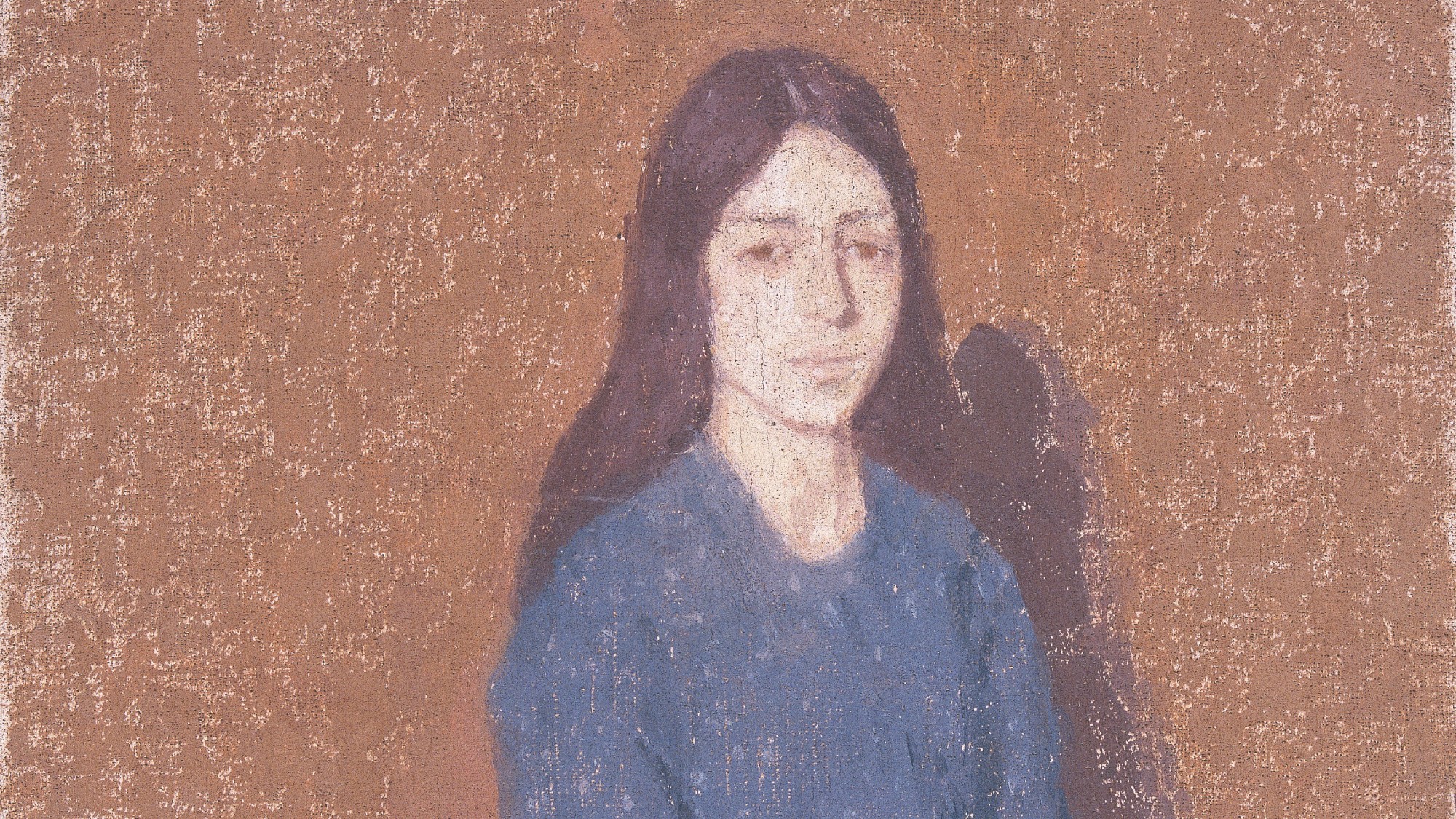

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10