Why Boris Johnson doesn’t have the political capital to give his father a knighthood

According to a political corruption expert the latest honours list controversy is ‘cronyism and nepotism at its finest’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sam Power, a senior lecturer and expert in political corruption at the University of Sussex explains how the former prime minister’s attempt to knight his own father is an example of his fading allure and the potential end of his political career.

As an academic specialising in part in why political corruption happens, the tenure of Boris Johnson (and its aftermath) has provided me with much to consider. Indeed, over the past 18 months, it has felt like I’m getting asked the same question over and over again. After the Owen Paterson affair: is this corruption? After the cash for curtains episode: is this corruption? Partygate: is this corruption?

We’ve had a pretty workable and simple definition of what corruption is for about 30 years. It is the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We can use this definition to answer the question in relation to the latest revelations about the Johnson family. The proposal to give Stanley Johnson, Boris Johnson’s father a knighthood: is it corruption?

We need to work from our above definition. Do we have entrusted power? Do we have an abuse? Do we have private gain? In two out of three instances here, we have an open and shut case.

Boris Johnson was prime minister and his father is reportedly being recommended in his resignation honours. Power doesn’t get much more entrusted than that. Is there private gain? Well, in the British system, there’s much to be gained from having a knighted businessman in the family.

The abuse issue is ever so slightly cloudier. We would have to wait to see the justification given for putting Stanley Johnson forward for a knighthood, but it comes down to: what would his knighthood be in service of?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even if one can make a pretty good case he is deserving of a knighthood, it will be incredibly hard to shake the not unreasonable perception that he’s only getting one because of who his son is – that it is cronyism and nepotism at its finest.

‘McNulty’ syndrome

One thing that became quite clear during Johnson’s time as prime minister is that he holds a different view to many on what constitutes acceptable and appropriate standards in public life. He has what I call, “McNulty syndrome”.

Like the famous character from The Wire, Johnson thinks of himself as a maverick. He may not play by the rules – but that gets results. He Gets Brexit Done. Just don’t question his methods.

Johnson has, in many ways, based his whole appeal on this approach. Those who like him do, in part, because he’s not like other politicians. He plays fast and loose with the rules. Those who hate him, do so precisely because they think he debases (and debased) the offices which he holds.

He has a unique appeal to a unique subset of voters – and that, some believe, makes him electoral gold dust.

Viewed in this light, Stanley’s reported knighthood is entirely unsurprising. It is a pattern of behaviour established throughout his son’s time in office. It is born, in part, of a basic electoral calculation.

When push comes to shove, the electorate cares far more about outcomes than process. Johnson believes that to voters, economy, health and (back in 2019, getting Brexit done) are far more important than honours lists.

Long-time frenemy Michael Gove was quite up front about this when reflecting on the 2019 campaign. You may remember Johnson took a few hits for refusing to be interviewed by the BBC’s Andrew Neil. When asked if this was a mistake, Gove’s answer was: “No. We won.”

The problem with this win-at-all costs approach is that it is based on a fundamental misreading of the terrain. There is good evidence outlined by the political scientist Will Jennings, that his unique political talents and appeal, while not to be dismissed, are often overstated.

And the public, in fact, do care about standards, ethics and honour. UCL’s Constitution Unit, for example, showed a high degree of support for reforming the current standards system.

They found the importance of politicians holding high moral standards to be of a similar importance to climate change. As the unit’s director, Meg Russell, argued: “There could be electoral rewards for politicians who respond” to public concerns about good behaviour.

Running out of road

The maverick schtick can get tired. Jimmy McNulty was interesting and effective in season one of The Wire but by season five he was (spoiler alert), staging murders with the bodies of dead homeless people. And (spoiler alert) that was pretty much that for Jimmy McNulty’s policing career.

Johnson should therefore beware. With more partygate revelations coming out over a year since the first, his behaviour in office continues to be a fly in the ointment for Rishi Sunak’s political project.

On the surface this might seem like misfortune for the current prime minister, who risks being tarred with the same brush. But a tactical advantage is also within his grasp.

The more Boris Johnson neglects widely agreed standards of appropriate behaviour, the more Sunak can put clear blue water between himself and his predecessor. We know that the public do care about ethics, and they do value these traits in leaders. What they don’t have, is unlimited patience with Johnson.

Ultimately, giving Stanley Johnson a knighthood shows that Johnson has learned nothing from his removal as PM. Aside from among a rump of Conservative MPs and party members, he is not as popular as he thinks.

People care much more about ethical behaviour and perceptions of competence than his calculations tell him. All this suggests that the knighthood looks a lot more like a plot line from a political show in its final season rather than its premiere.

Sam Power, Senior Lecturer in Politics, University of Sussex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’the week recommends The pasta you know and love. But ever so much better.

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Three consequences from the Jenrick defection

Three consequences from the Jenrick defectionThe Explainer Both Kemi Badenoch and Nigel Farage may claim victory, but Jenrick’s move has ‘all-but ended the chances of any deal to unite the British right’

-

The MAGA civil war takes center stage at the Turning Point USA conference

The MAGA civil war takes center stage at the Turning Point USA conferenceIN THE SPOTLIGHT ‘Americafest 2025’ was a who’s who of right-wing heavyweights eager to settle scores and lay claim to the future of MAGA

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

What does the fall in net migration mean for the UK?

What does the fall in net migration mean for the UK?Today’s Big Question With Labour and the Tories trying to ‘claim credit’ for lower figures, the ‘underlying picture is far less clear-cut’

-

Asylum hotels: everything you need to know

Asylum hotels: everything you need to knowThe Explainer Using hotels to house asylum seekers has proved extremely unpopular. Why, and what can the government do about it?

-

Five takeaways from Plaid Cymru’s historic Caerphilly by-election win

Five takeaways from Plaid Cymru’s historic Caerphilly by-election winThe Explainer The ‘big beasts’ were ‘humbled’ but there was disappointment for second-placed Reform too

-

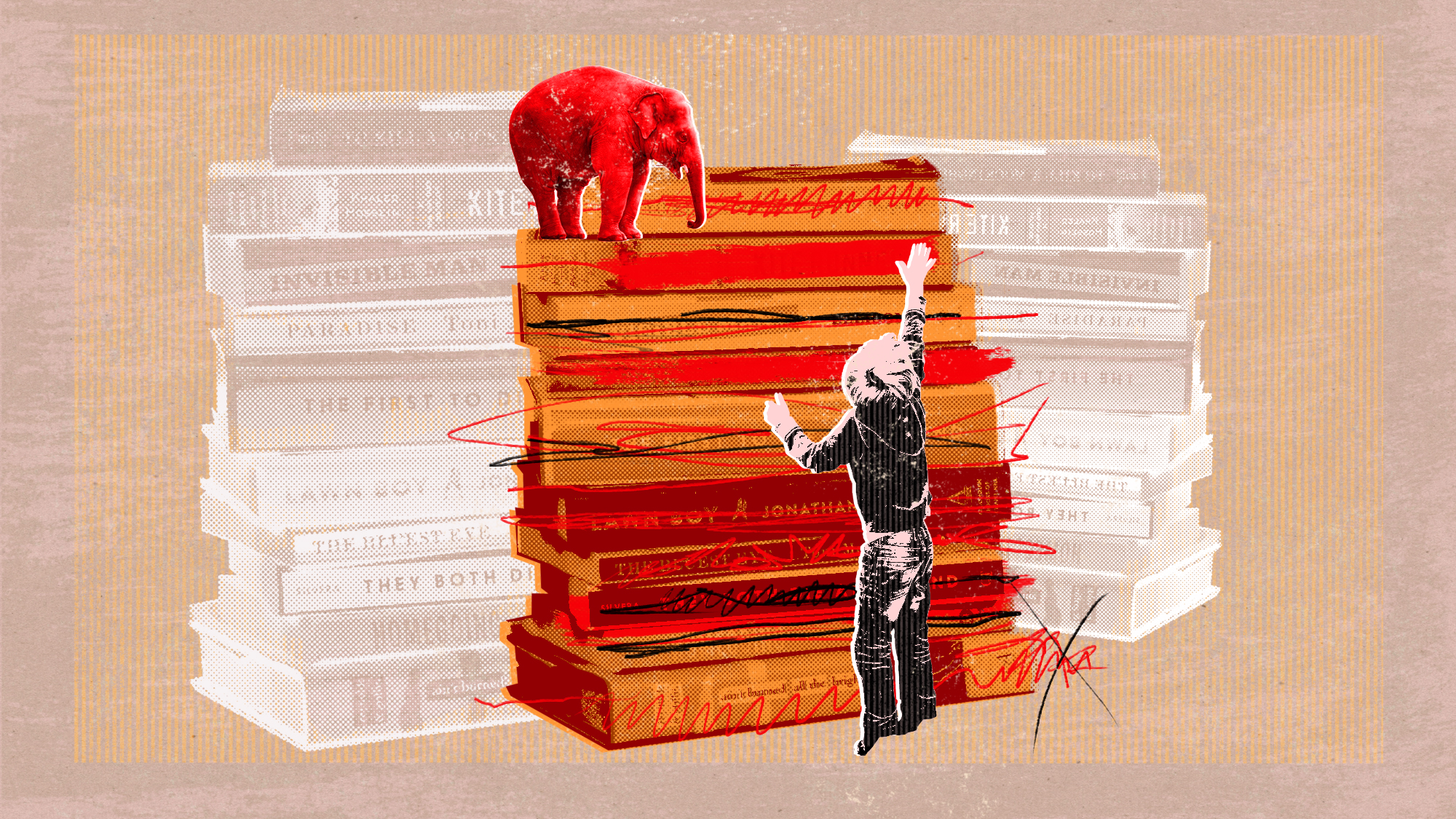

The new age of book banning

The new age of book banningThe Explainer How America’s culture wars collided with parents and legislators who want to keep their kids away from ‘dangerous’ ideas