How TikTok conquered the world

The Chinese-owned video app is expected to have 1.8 billion users by the end of the year

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the five years since TikTok launched, the mobile phone app once regarded as a teen dance fad has ballooned into one of the most dominant – and politically controversial – media platforms in the world.

It has grown past one billion active users faster than any other social network: it has about 17 million users in the UK, more than 130 million in the US, 99 million in Indonesia and 74 million in Brazil; users are expected to top 1.8 billion by the end of the year.

It sucks people into an infinite stream of content, for hours on end – so much so that the company has had to implement warnings about screen time and reminders for people to “take a break” or, failing that, just to “get some water”. It is a platform that is helping to shape how a generation perceives the world – and as it does so, it gathers vast amounts of information about its users for its Chinese owner, ByteDance.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Who owns TikTok?

TikTok evolved out of Musical.ly, a Shanghai-based app founded in 2014 on which users shared short lipsyncing videos. In 2016, a tech firm, ByteDance – set up in 2012 by two young Beijing-based software engineers, Zhang Yiming and Liang Rubo – launched a similar service, Douyin, which acquired Musical.ly and merged the two in 2018. Douyin is still the Chinese version of TikTok. The two share an interface, but have no access to each other’s content.

TikTok has long faced scrutiny from US lawmakers, who have questioned its exploitation of user data. In 2020, a US national security panel ordered ByteDance to sell the US TikTok service because of fears that US user data could be passed on to the Chinese government. US lawmakers and TikTok are now negotiating a plan, under which it would change its data security and governance without requiring a sale.

ByteDance, which bills itself as primarily an AI company, recorded $18.3bn in revenue during the first three months of 2022. According to Forbes, Zhang Yiming is worth $49bn and is China’s second-richest person. TikTok faces competition, though: YouTube has launched a successful copycat version, YouTube Shorts.

How does it work?

TikTok is an app for sharing short video clips made by other users, varying from 15 seconds to a maximum of ten minutes, though the average is under a minute. The videos play on a loop; users navigate their feed in the app by scrolling up and down. The key difference between it and, say, Twitter, Facebook or Instagram is that you don’t have to search for the subjects or celebrities you’re interested in, or link up with friends.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The “For You” page simply starts showing you a never-ending stream of TikToks. The more it learns about you, the more the feed becomes streamlined towards not what you say you would like to watch, but what you actually watch (though you can still search for your interests, or follow people whose content you enjoy).

Its machine-learning algorithm gathers data about your tastes every second you watch, pause or scroll, tailoring your feed accordingly. In this sense, says The New York Times, “TikTok is more machine than man”.

What are TikTok videos like?

TikTok started with dancing and lip-syncing – music has always been central – but its content has ballooned to cover just about any subject you can imagine. Videos of beauty and styling tutorials are popular, as are cooking videos and, of course, videos of cute animals and babies. A video of “Mia the cat” successfully navigating a path laid over upturned paper cups, set to the Mission: Impossible theme tune, has been viewed almost 200 million times.

However, the hashtags used to mark and filter content range from #fishtok (content about fishing, 16 billion views), to #cleantok (57 billion), #farmtok (8 billion) and #medievaltiktok (4 billion). #booktok (92 billion) – videos of people enjoying or talking about books – supposedly boosted the publishing industry to one of its best years ever in 2021.

How do people make videos?

TikTok makes it very easy to create them, with a toolkit of camera effects, editing tools, augmented-reality filters and, crucially, a massive library of audio clips. These range from snippets of popular songs that have sparked dance trends to audio from TV and films. Users also use the “green screen” feature to, for instance, commentate on another video as a “response”, or create a “duet” by adding themselves alongside another video.

The app provides extensive prompts and ideas for your content. You can participate in dare-like challenges, copy a dance, or make fun of anybody else doing the same. Popular content creators make money through advertising deals, creator payouts from TikTok, and by receiving TikTok “coins” – the network’s virtual currency – from fans. In the three months to October, “TikTokers” spent $900m inside the app.

Who is watching TikTok?

Two-thirds of US teens use the app, and one in six say they are on it “almost constantly”. The average American TikTok viewer spends 80 minutes a day on it; that’s more than users spend on Facebook and Instagram combined. In the UK, Ofcom says that TikTok reaches 66% of 15-24-year-olds, and that adult users, on average, spend almost an hour on TikTok each day. It is also, along with Instagram and YouTube, one of the UK’s most popular news sources for teens.

But it’s not just teenagers who use it: half of US users are over 25. In short, it is vastly important for advertising, and is capable of creating viral hits and stars overnight.

Why is it so addictive?

Obviously the content is entertaining. But the design of the app helps to make it addictive, too. Engagement with TikTok is predominantly passive. Few decisions are required: watching the next TikTok involves only a simple flick of the finger. As investment analysts at Bernstein Research pointed out, TikTok has replaced “the friction of deciding what to watch” with a “sensory rush of bite-sized videos… delivering endorphin hit after hit”.

“Every swipe could bring something better,” says The Washington Post, “but viewers don’t know when they’ll get it, so they keep swiping in anticipation of something they might never find.”

“Once immersed in the flow-like state, users may experience a distorted sense of time in which they do not realise how much time has passed,” noted a researcher from Brown University.

Should we be worried about TikTok?

As with other social media, TikTok has raised many concerns. Its use has been associated with adverse health impacts such as anxiety, depression or poor sleeping habits; it has also been accused of shrinking users’ attention span.

The sheer size of TikTok’s audience and influence means that there has been concern about its content, from misinformation to obscenity to censorship: the system by which content is suppressed or promoted is opaque.

ByteDance has tried to allay such fears by being increasingly transparent about how its algorithms work – an unusual move in an industry where code is often top secret. But it does not help that it is run from a totalitarian state that leads the world in digital surveillance.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 years

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 yearsfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?Talking Point Goverment under pressure to prohibit breed blamed for series of fatal attacks

-

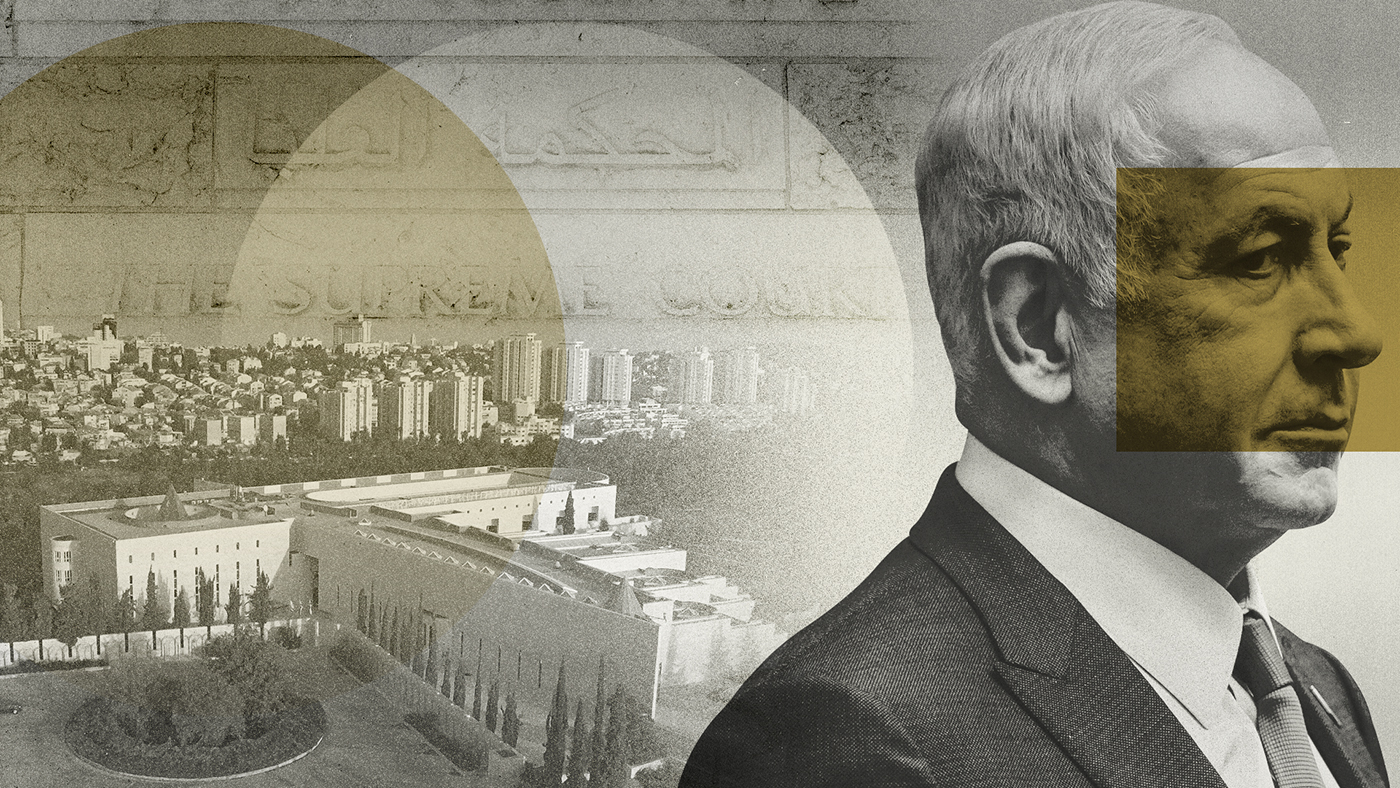

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?feature The nation is divided over controversial move depriving Israel’s supreme court of the right to override government decisions

-

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wife

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wifefeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?feature Brussels has pledged to give €100m to Tunisia to crack down on people smuggling and strengthen its borders

-

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled haven

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled havenfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classes

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classesfeature Reports of the death of the Chinese economy may be greatly exaggerated say analysts

-

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Nato

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Natofeature While Swedes believe it will make them safer Turkey’s grip over the alliance worries some