How an Alabama brawl became a watershed moment for race in America

"No people are obligated to endure violence without defending themselves or being defended"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Montgomery, Alabama, police have arrested three white men for their alleged roles in the attack on a Black riverboat co-captain who tried to get them to move a pontoon boat improperly parked in the spot reserved for the riverboat, the Harriott II. The co-captain, Damien Pickett, had been ferried ashore from the riverboat, which was stranded for a half-hour waiting for its spot with 227 passengers on board, and was jumped as he talked to several white men who piled on, punching him.

Black bystanders rushed to Pickett's defense. A Black deckhand swam to the dock from the boat to help. Video of another man smacking a white man and woman over the head with a folding chair inspired a stream of memes showing folding chairs in the hands of civil rights icons, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Harriet Tubman. "No one is condoning violence," a Montgomery native said. "But I'm proud of the way we responded because if we don't, then what? We'll see it again."

Video of the melee went viral. Supporters of the bystanders said the violence was unfortunate but those who rushed to Pickett's defense did the right thing. An unidentified 67-year-old man who was with a high school reunion group taking a two-hour riverboat cruise said on Chris Coleman's "Think Tank," a radio show on V 99.5 in Birmingham, that the incident "made me proud of Black people." Montgomery police said they were charging the white suspects — Richard Roberts, 48; Allen Todd, 23; and Zachary "Chase" Shipman, 25 — with third-degree assault, but not with racist hate crimes pending further investigation. So how did this dockside brawl become what some are calling a watershed moment for race?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"White privilege got its ass whupped"

"White privilege met Black pride down by the Alabama River," said Elie Mystal in The Nation, "and on this particular occasion, white privilege got its ass whupped." To understand why so many people are taking joy in such an ugly spectacle, you have to know more "about the history of white violence against Black people in this country than a person currently being educated in Florida." White people who attack Black people "in broad daylight always think they'll get away with it. Usually, they're right." Not this time. "And privileged white racists learning they are wrong in real time is a joy to behold."

The viral video was cathartic, said Touré in The Grio, because after seeing "so many viral videos of Black people getting beaten up or killed," we finally saw one where the bad guys got what they deserved. Black people "are celebrating this beatdown like we all just got reparations" because this shows the power of "collective responsibility in action." These videos, taken by people on the riverboat, show "Black people having one another's backs." It is "heartwarming" and empowering "to know that maybe one day if some white boys jump you, the cavalry will come running to save you, too. Because whatever power we have in this country comes from us standing together."

Where it happened mattered

The location, a riverfront where enslaved people were once sold in a city that briefly served as the capital of the Confederacy, gave the event symbolic meaning, said Curtis Bunn in NBC News. There is "history woven into Montgomery's fibers." It was the scene of a 1955 bus boycott at the start of the civil rights era. That history, "fueled by oppression and then Black resistance of the 1950s and '60s, likely emboldened the Black people who came to Pickett's aid," locals noted.

The "Alabama Sweet Tea Party" was unfortunate but "practically unavoidable," said Charles M. Blow in The New York Times. Black people have been brutalized since the days of American slavery, "with others, generally, unable to defend them." The civil rights movement met "violence with nonviolence," highlighting the cruelty of Southern racists but generating "another volume of imagery of Black victimization — beatings, fire hoses, lunch counter mobs." Seeing "Black people coming to the defense of that Black man" marked "a departure," giving people around the nation "a sense of historical correction" making it plain that "no people are obligated to endure violence without defending themselves or being defended."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Can unbuilding highways undo the legacy of racism?

Can unbuilding highways undo the legacy of racism?Speed Read Roads were built through Black and Latino neighborhoods. A new federal program may reverse those efforts.

-

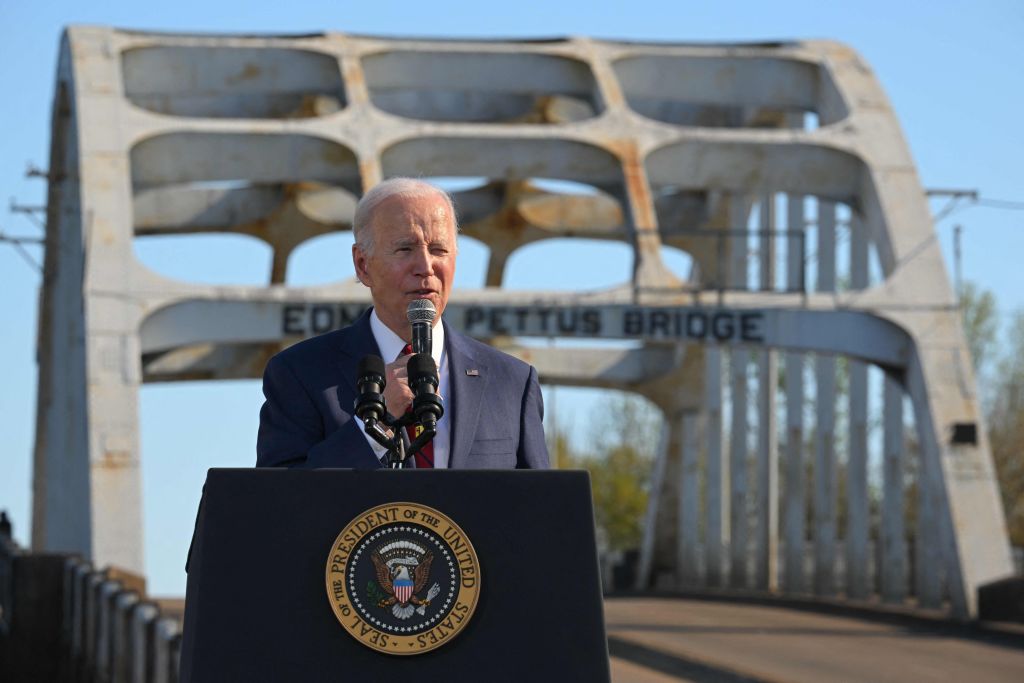

Biden commemorates Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama

Biden commemorates Bloody Sunday in Selma, AlabamaSpeed Read

-

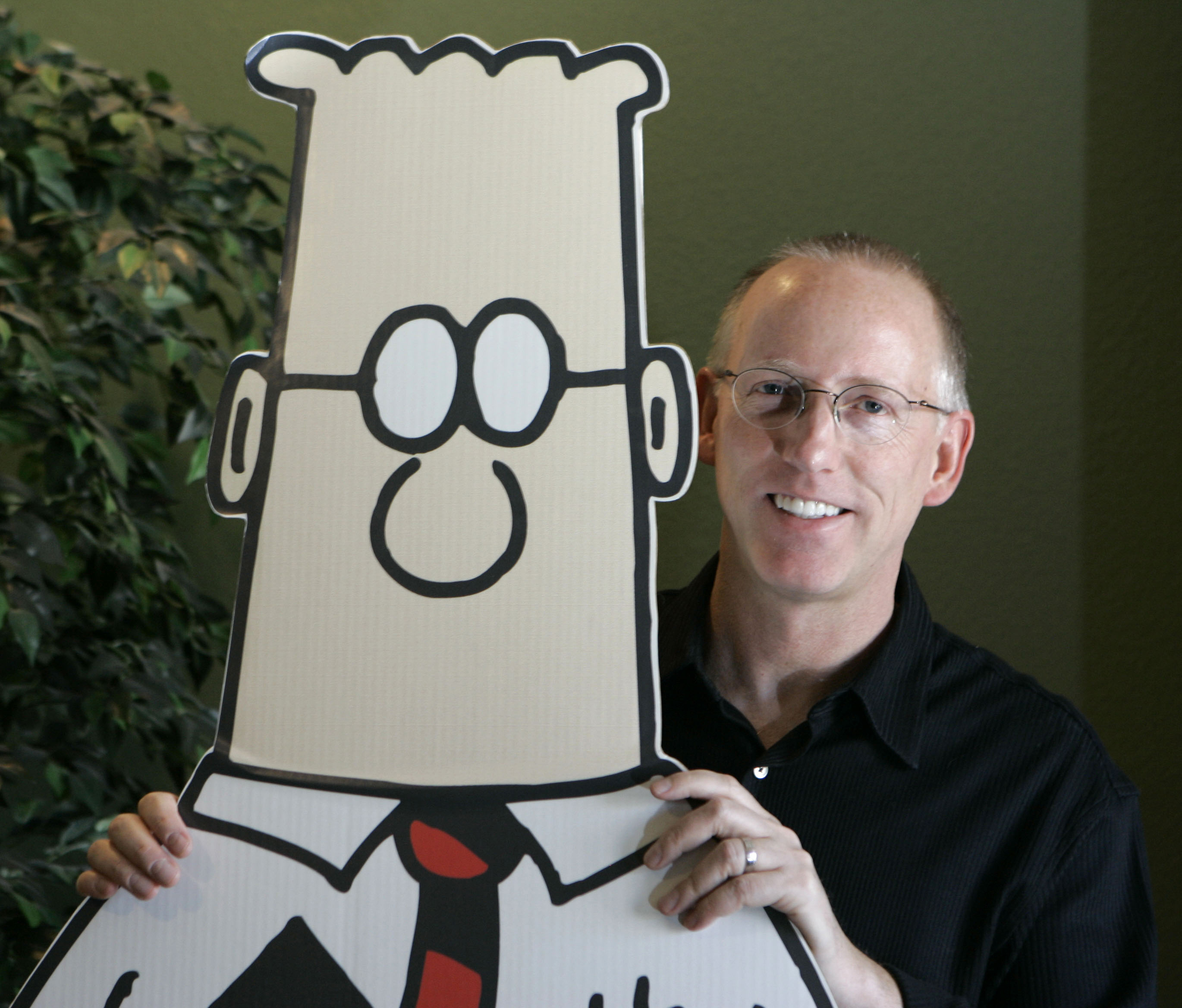

The Dilbert debate: Were newspapers right to 'cancel' the cartoon?

The Dilbert debate: Were newspapers right to 'cancel' the cartoon?Instant Opinion The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

Newspapers drop Dilbert comic strip over creator's racist remarks

Newspapers drop Dilbert comic strip over creator's racist remarksSpeed Read

-

Food vendor apologizes for serving culturally insensitive school lunch on 1st day of Black History Month

Food vendor apologizes for serving culturally insensitive school lunch on 1st day of Black History MonthSpeed Read

-

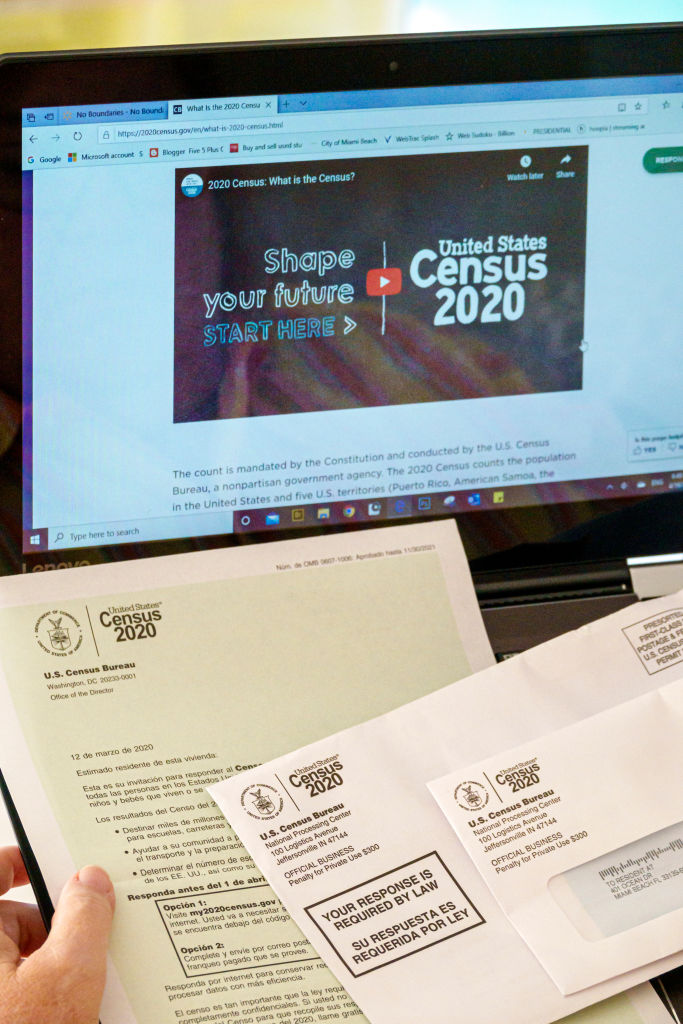

Federal working group proposes new 'Middle Eastern or North African' category for next census

Federal working group proposes new 'Middle Eastern or North African' category for next censusSpeed Read

-

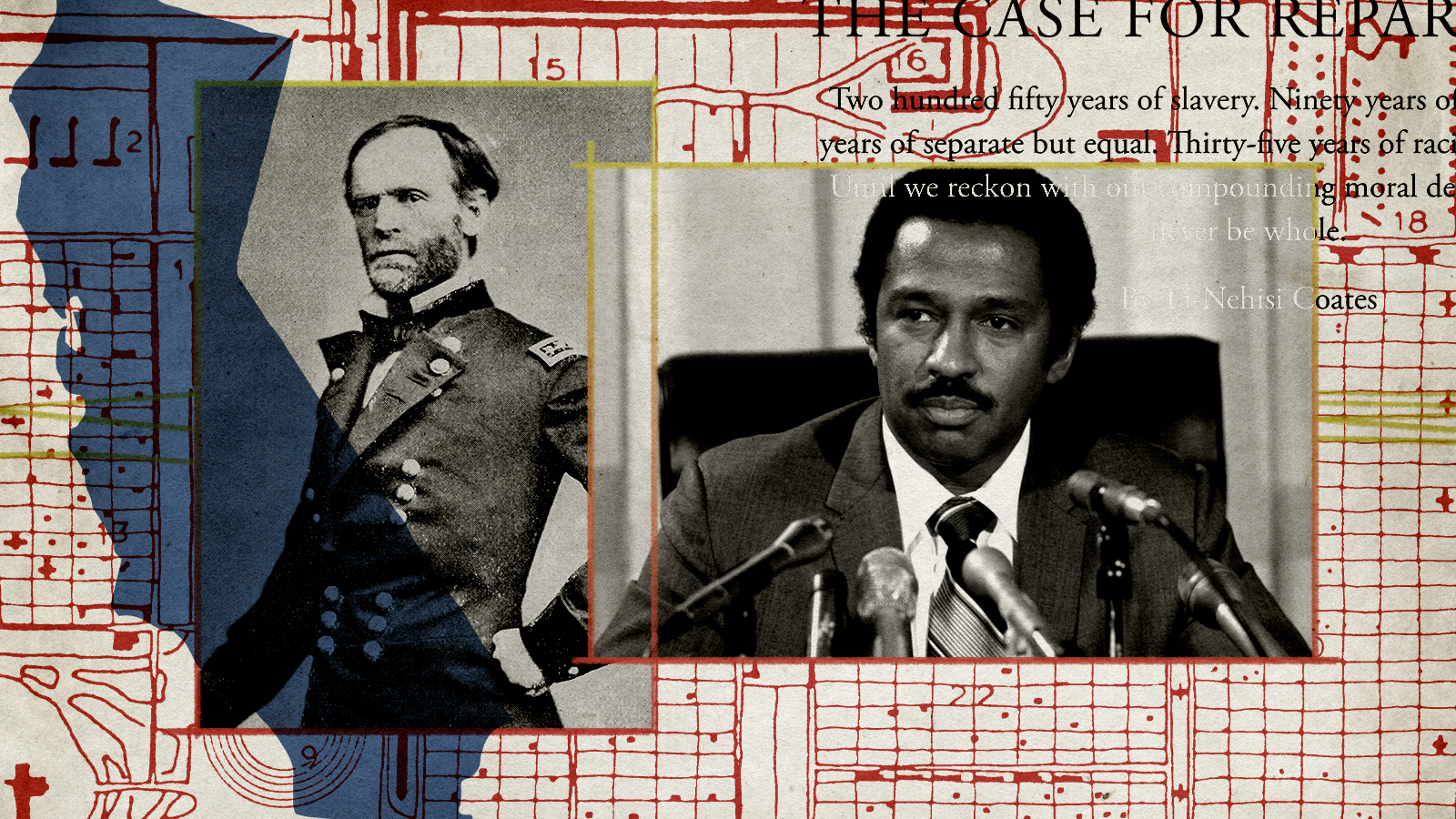

Why California is considering reparations for racism

Why California is considering reparations for racismSpeed Read And why the idea is spreading

-

Escaped Alabama inmate and corrections officer found in Indiana after 10-day manhunt

Escaped Alabama inmate and corrections officer found in Indiana after 10-day manhuntSpeed Read