Who benefits most as NFTs become more 'real'?

Blockchain is playing a growing role in Hollywood

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since they emerged into the public consciousness last year, the joke about NFTs — unique or non-fungible tokens, mostly in the form of digital art — has been that buying one gets you nothing but an easily right-clickable jpg. Spending money on an NFT seems like paying to "adopt" a panda or name a star in the sky: more the feeling of ownership than anything real. But that is changing fast.

Creators have begun to attach benefits to their NFTs, like access to real-world events or exclusive Discords, building a high-tech fan club with NFTs as tiered membership dues. And once that paying audience exists, NFTs are proving to be a shiny new form of creative intellectual property (IP), giving creators the opportunity to license characters and sell movie rights to major media companies for real-world money.

It's a story that's new and tired at once: Because NFT rights management is still the Wild West, there is no standard practice for how rights are sold or what constitutes a good deal. While this opens the door to new talent that can leverage the technology without traditional media gatekeepers, some creators are going into contracts that give away rights to their IP without the protections of managers or agents, leaving them open to exploitation from Hollywood's age-old hunt for fresh meat.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Huge NFT players Bored Ape Yacht Collective (BAYC) and World of Women (WoW) have even introduced an entirely new rights model where IP fully transfers from the creator to the buyer at purchase — allowing NFT owners to make money directly from licensing and any derivative works — further blurring the lines between fan, creator, and investor in a way that is uniquely Web3.

In Hollywood, IP may be king but an audience is the key to any content's survival, according to Denise Hewett, a long-time television and digital producer turned startup founder. "That's why they auction best-selling articles and best-read books, because of a built-in audience base." And NFT communities have grown exponentially recently — in crypto market value not actual numbers, since most NFT collections cap their NFTs and therefore primary-market community members at 10,000 (usually, owners retain rights to resell their NFTs on a secondary market).

The most visible communities, like BAYC and Flower Girls, include celebrities like Justin Bieber, Madonna, Gwenyth Paltrow, and Snoop Dogg, who each have bought NFTs for hundreds of thousands to over a million dollars. These celebrities may be genuine fans of the artwork, but by buying NFTs, they are also investing in the community's future endeavors — an incentive structure that's very different from a literary fan who may have shelled out $24.99 for a hardcover novel but whose connection to the art and artist ends there. For BAYC NFT buyers (who each paid a minimum of $288,000), their significant investments may have paid off when the company released an ApeCoin to its community members first, giving owners like Justin Bieber first run at millions of dollars worth of cryptocurrency.

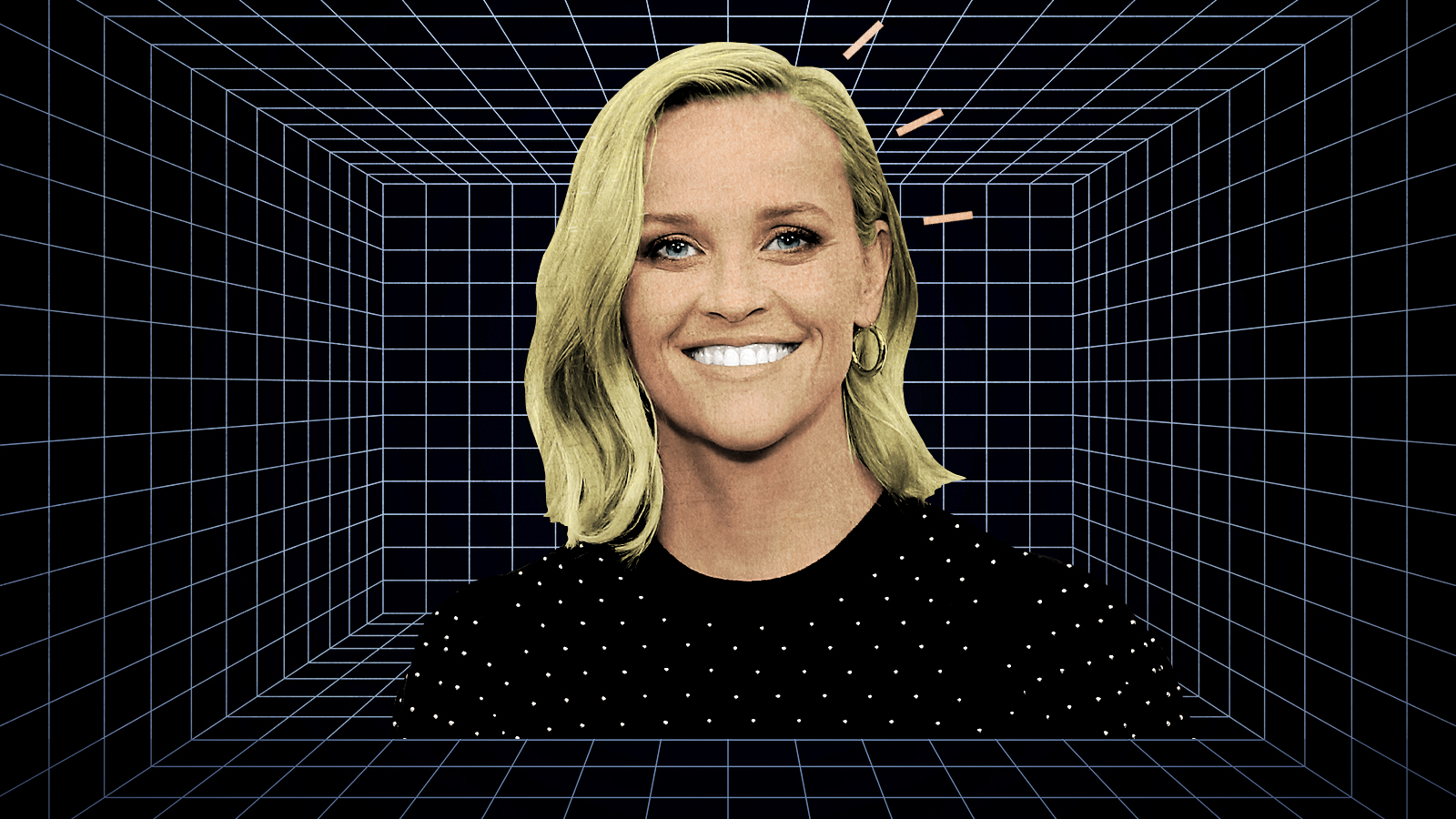

BAYC has even just released merch that can only be bought with ApeCoin, adding new layers (and price tags) to the BoredApe universe. And in some cases, that blurry line between fan and investor can even appear more cynical. For instance, Reese Witherspoon bought multiple World of Women (WoW) NFTs — the same collection her production company Hello Sunshine later announced a media partnership with. As an NFT owner and therefore investor, Witherspoon likely stood to benefit from both sides of the deal — which would be legally suspect in other industries.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But like many in the Web3 space, Brinton Bryan, a film producer and the founder of blockchain fintech startup Cinebloc, sees huge positive potential for these communities to serve as a new kind of ready-made marketing team. "These people form their own little armies, and they go out and shill these projects. They want other people to get into them because it raises the investment of the digital assets that they own."

That relationship may be beneficial for smaller creators who may not have been able to afford marketing otherwise — like Micah Johnson, whose NFT Aku was the first to be optioned for film and TV last year. And unlike traditional media artists who must split any revenue with agents, managers and creative partners, NFT creators may stand to gain more from ensuing media deals. But there is danger in that kind of pioneering mindset — especially when these deals have little to do with anything unique to NFTs.

"The nice thing about blockchain is there is transparency," said Hewett about the public record aspects of the technology. "But if I option rights to an NFT, that's a separate deal that's not happening on the blockchain. That's probably a traditional Hollywood deal, and it's very easy for creators to get left behind." Unlike NFT ownership history inscribed in the blockchain, the terms of those media deals are kept private.

Both World of Women and Bored Ape Yacht Club have pushed the rights envelope even further this year and introduced a new model where NFT buyers get full IP of their purchase, transferring the right to license and create derivative works from the creator to the owners. "Publishing and a lot of other media companies work in the exact opposite way," said Kate McKean, VP at Howard Morhaim Literary Agency and creator of the popular Agents+Books newsletter. "And that makes me even more disinterested in [NFTs], because we're not talking about the same thing at all." And for Web3 die-hards that may be the point.

The Web3 creator mindset is closer to internet fan culture than traditional media structures. The bigger the NFT character universe gets, the better for the creator and the Web3 world more broadly.

"One reason why creators are willing to forego IP rights is that they can benefit from it through successful derivative works of their IP — any future sales of the NFTs bring in secondary market royalties," said Simon de la Rouviere, founder of Untitled Frontier, a creative studio experimenting with storytelling in Web3 models.

"It's all good for everyone involved because both the creator and derivative creator can earn from it. The equivalent is to a Star Wars fan-fic writer earning from selling this fan-fic AND also earning from owning Disney shares at the same time. There's a counter-intuitive value loop here," he added. For Web3 entrepreneurs like de la Rouviere and Bryan, audience is the goal, and IP is the fair price of scaling.

But even those deep in Web3 culture acknowledge there's still a lot to be worked out in the space, despite the recent spotlight. While de la Rouviere believes new models to support creative work are critical to allow space for smaller or weirder works, he admits that "the tenuous link between the NFT and the actual work will also likely be tested in courts in the next few years."

And the premise that individual NFTs are even uniquely copyrightable may get legal pushback as well. San Francisco-based lawyer Andrew Gass who specializes in emerging forms of IP points out that "the work that is linked to NFTs is attracting a ton of attention. That makes the IP in that work potentially valuable, even though the linkage to the NFT isn't generally what's going to yield the IP." Rather, the combination of images and words — including any website copy with an accompanying narrative as is common for NFT collections — could yield copyrightable characters, just as they would for a comic book character. The fact that the NFT is a digital token is mostly beside the point.

But like so much in Web3 and crypto, while the future is still working itself out, huge amounts of money are going into high-profile NFT projects ($10 million dollars in World of Women transactions took place in one week alone), and investors are making money right now off the potential of the space while questions of access still remain.

Many NFT collectives — particularly women-led ones — offer charity donations and NFT giveaways, which give a sheen of accessibility. However, the NFT ownership system — like an art market — is designed to raise prices to the level of demand, restricting entry to these "communities" to those who can afford thousands of dollars (if not millions) in NFTs.

If we keep barreling down this path without thinking through the legal questions of ownership — and which if any are related to NFTs as a unique form of creative work — the smaller artists who may be hoping to benefit from the technology's democratizing sales pitch, are going to be at serious risk of exploitation by the same old power players of new media formats that have come before.

Rebecca Ackermann is a writer, designer, and artist living in San Francisco. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Wigleaf, and elsewhere. As a designer, she has worked on AI for healthcare, VR for education, and consumer transparency tools with Google, NerdWallet, and others. In a previous life, she staffed at NYC independent magazines Heeb and Index.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day