Breaking Bad series finale recap: 'Felina'

The AMC drama let a triumphant Walter White end the story on his own terms. But is that a good thing?

I had imagined a darker ending for Breaking Bad — a version of this story in which Walt's money remained, Ozymandias-like, in a hole in the desert, serving as a reminder of how meaningless all his terrible crimes really were. A version in which Skyler, the woman who has been forced to carry the weight of Walt's crimes around like a ball-and-chain, would end up serving time in prison for her reluctant role in them. A version in which Breaking Bad dutifully followed the arc of the classical tragedy it seemed to be for so much of its five-season run: The story of a desperate man attempting to save his family, who ends up destroying it instead.

Instead, we got tonight's "Felina," a series finale in which everyone we care about got exactly what they wanted — or, at the very least, the best they could hope for at this very late stage of the game. Skyler now has enough leverage to cut a deal with the DEA and make a clean break. Marie will get to recover Hank's body and give it a proper burial. Jesse got to kill Todd and escape to whatever kind of life he can piece together now. Walt managed to ensure that his own children would actually benefit from the fruits of his labor and — perhaps most pivotally, for a man who's been dying of terminal cancer since the series began — got to end his life on his own terms.

At this point in Breaking Bad, Walt's life has long been divided between two personas: Walter White, a "sweet, kind, brilliant man" who Gretchen Schwartz declared dead at the end of last week's episode, and Heisenberg, an elusive chemical genius who delivered high-grade methamphetamine to Europe long after the actual "Heisenberg" had retreated to a remote cabin in New Hampshire.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In theory, Heisenberg could have lived long after Walter White was dead — but "Felina" gave us the definitive ending of both. By the end of "Felina," Walter White is dead. But more unexpectedly, so is the international meth empire Walt unwittingly set in motion when Breaking Bad first began. By dispatching both his distributor Lydia and Todd — the imperfect Frankenstein monster he created — Walt has also ensured that Heisenberg's greatest legacy will die with him; no one is left to cook and sell any more of his now-legendary blue meth (unless Jesse has a serious change of heart at some point in the future).

Meanwhile, all Breaking Bad's "bad guys" are dead, from Uncle Jack (who took a bullet to the head) to Todd (who took a chain to the throat) to Lydia (who was undone by her inability to distinguish Stevia from ricin). "Guess I got what I deserved," is the first lyric of Badfinger's "Baby Blue," which serves as the final song in a long line of pitch-perfect song choices for Breaking Bad — and it’s tough to argue that any of the show's clear-cut villains didn't deserve their grisly fates.

But did Walter White get what he deserved? Series creator Vince Gilligan originally pitched Breaking Bad as a show that would take Mr. Chips and turn him into Scarface, and he was true to his word: The end of "Felina" sees Walter White unleash his own little friend on all of the Nazis, defeating the last in a chain of enemies that began with low-level dealers like Krazy-8 and reached the heights of major players like Gus Fring. After a brief period of exile, Walter White successfully returned to Albuquerque and proved that he's the king again; he may be dead, but he's dying with a smile on his face in a meth lab.

I've always believed that Breaking Bad takes place in a rigidly moral universe — a place in which Walter White's sins manifest themselves as a plane crash over Albuquerque, and where an attempt to destroy a potentially incriminating laptop with a magnet ends up giving the police the definitive evidence that was hidden behind a picture frame. "Just get me home. I'll do the rest," says Walter, in a kind of desperate prayer, as he sits in a stolen car at the beginning of "Felina" — and suddenly, like manna from heaven, the car's keys fall into his lap from the vanity mirror. What kind of divine intervention can be interpreted from that?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Don't get me wrong. It's been a long time since I've actively rooted for Walter White, but I didn't want to see a finale that spent an hour rubbing his nose in the dirt for all the terrible things he's done over the course of the series. Breaking Bad's previous two episodes, "Ozymandias" and "Granite State," have taken Walter White to harrowing lows that carry the full weight of his crimes, and "Felina" rightly gives him the chance to atone for some of them.

But there's a difference between redemption and triumph. On the "redemption" front, "Felina" offered several scenes that were an unqualified success. Let's flash back all the way to Breaking Bad's pilot episode, which featured Walter's first near-death confession, as he stood in the desert after his disastrous early attempt at cooking. Walter ended that self-shot video confession by speaking directly to his family, promising them that "no matter how it may look, I only had you in my heart."

Since that first episode we've heard Walt proclaim, ad infinitum, that all of his crimes were for the good of his family. It wasn't until "Felina," in his last-ever conversation with Skyler, that we heard him finally confess the true motive that's been clear ever since he turned down Gretchen and Elliott's money in Breaking Bad's first season. "I did it for me. I liked it," said Walt, in the episode's best scene. "I was good at it. I was really… I was alive."

It was, finally, a true confession from a man who'd spent so much of Breaking Bad spinning an endless web of lies. Just as importantly, it was a moment that felt honest — the truth from a man who'd run out of reasons to lie, and who spent much of "Felina" wandering around, purposefully but emotionlessly, executing his own final will and testament as he prepared for the death he knew was coming.

But the unqualified victory that Walt achieved in this final hour is a harder pill to swallow. From the moment the car keys fall into his hands, Walt's hastily conceived master plan goes off without a hitch. His drug money won't be for nothing; while Walter Jr. will never know it wasn't from Gretchen and Elliott, Walt can die knowing he truly did leave something for his family. Walt gets his final moments with Skyler and Holly because he manages to evade DEA surveillance, though it's not entirely clear how. Walt's victory over the Nazis relies on a series of lucky breaks: Kenny doesn't object when Walt parks his car away from the space he's been told, and Jack inexplicably feels the need to prove he wouldn't team up with a "rat" before killing Walt anyway.

Even Walt's last-minute improvisations end in success: Though it's clear he doesn't decide to spare Jesse until he realizes Jesse is being kept prisoner, Walt manages to save his former partner from the gunplay as the rest of the room is busy being shot to death. Jesse rightly refuses to shoot Walt, telling him to do it himself. But even in that key moral decision, Walt is given an out: He's already gut-shot from the machine gun stowed in the trunk of his car, which ensures that he won't serve time for his crimes while sparing him the weight of a deliberate suicide.

After so many crimes, "Felina" was surprisingly easy on Walt, and I suspect the show's ultimate moral message will be a source of debate and controversy as critics and fan continue to hash out Breaking Bad's legacy in the years to come. ("The whole thing felt kind of shady, like, morality-wise," said Skinny Pete, in a quote that could easily serve as an epigram for "Felina.") It was undeniably rousing to see Walt achieve that last victory, but it lacked the bravery of an episode like "Granite State," which might have offered a more fitting end for our antihero: Dying alone, next to a pile of useless money, thousands of miles away from anyone and anything he ever loved.

Instead, Walt got what I suspect many Breaking Bad fans were looking for: A chance to say goodbye. Over the course of "Felina," we see Walt visit a number of the people he's loved and relied on at different stages of his life: Gretchen and Elliott, Skyler and his children, Jesse Pinkman — even Hank makes an appearance, in a flashback to the moment that drove Walt to break bad in the first place.

But to its credit, Breaking Bad ends the story exactly where it should: In the lab, as Walt spends his final moments alone in the one place he's always truly belonged. The last time Breaking Bad offered a shot like the one that ends the series, it was at the end of season four's penultimate "Crawl Space," as Walt cackled maniacally at the desperation of his plight. Here, the same remarkable shot is deliberate and peaceful; after saying goodbye to the lab one last time, he sprawls on the floor and waits to die. For better or worse, this is where Breaking Bad's stunning, five-season story draws to a close. After so much struggle, Walter White managed to end on his own terms — and Breaking Bad, which defied expectations to the very end, managed to do the same.

Read more Breaking Bad recaps:

- Breaking Bad recap: 'Granite State'

- Breaking Bad recap: 'Ozymandias'

- Breaking Bad recap: The ticking time bomb

- Breaking Bad recap: 'Rabid Dog'

- Breaking Bad recap: The bogus, manipulative 'confessions' of Walter White

- Breaking Bad recap: Buried money, buried secrets, and buried motivations

- Breaking Bad premiere recap: "Blood Money"

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.

-

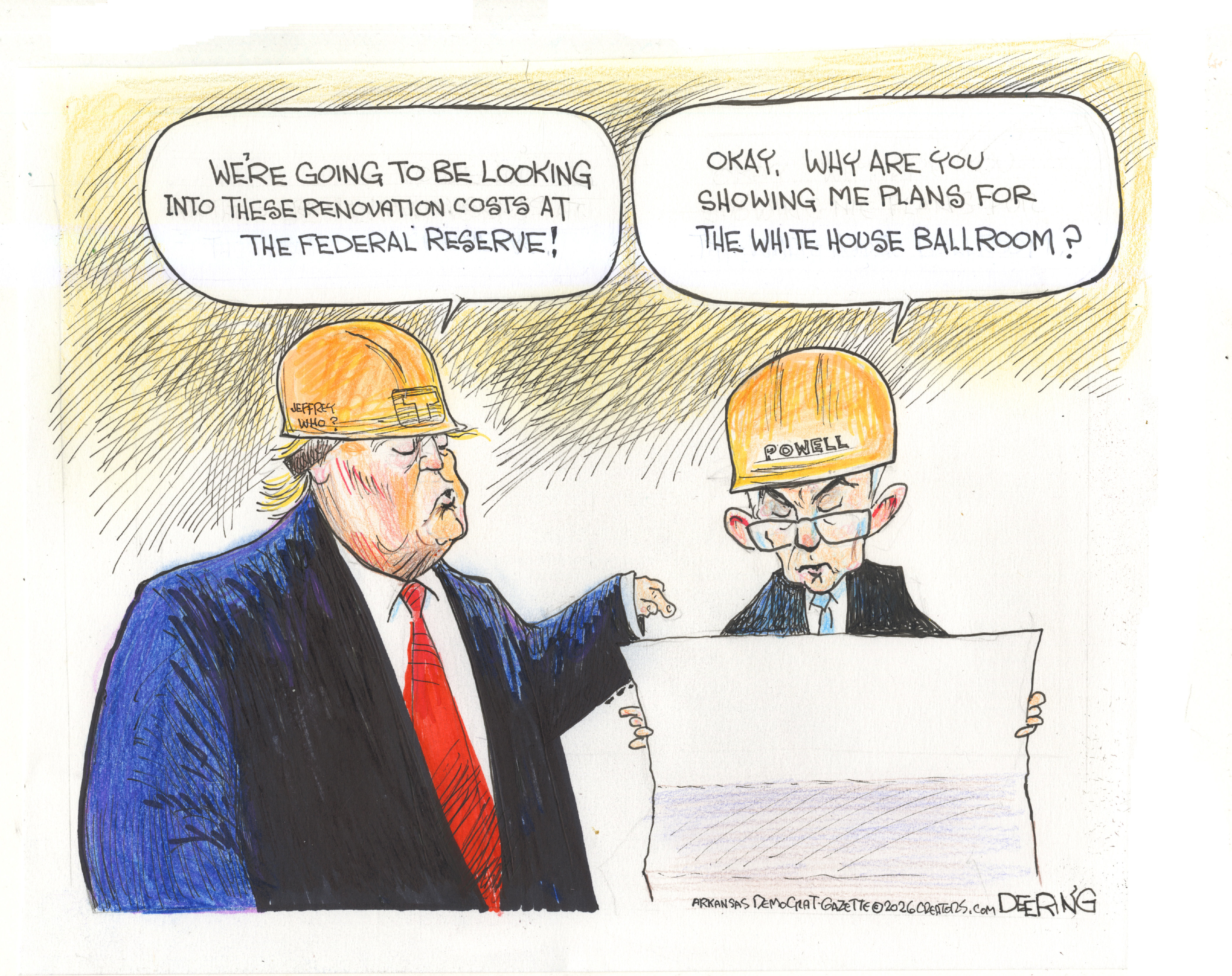

Political cartoons for January 17

Political cartoons for January 17Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include hard hats, compliance, and more

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’