Should dogs have the same rights as humans?

The case for making man's best friend his equal

Everyone knows that dog is man's best friend — but is he his equal? As odd as it may be to imagine Lassie, Old Yeller, or Comet as part of the human family, a new case is being made that canines deserve at least some of the rights and protections of humans.

Professor Gregory Berns at the New York Times argues that "dogs are people, too," based on evidence from unprecedented brain scans he and his colleagues at Emory University are conducting.

While conventional veterinary practice says dogs must be anesthetized before they are placed in an M.R.I., Berns and his team have been training dogs to remain in the M.R.I. of their own accord. With the dogs full cognizant during these scans, their early research has led them to discover "a striking similarity between dogs and humans in both the structure and function of a key brain region."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That region is the caudate nucleus, a part of the brain that is activated when we sense things we enjoy, such as food, love, and money. It turns out, dogs also have increased caudate activation when exposed to hand signals indicating food or even when an owner walks back into a room after stepping out.

This brain activity suggests dogs feel emotions similarly to humans. And that has some very serious implications, says Berns:

The ability to experience positive emotions, like love and attachment, would mean that dogs have a level of sentience comparable to that of a human child. And this ability suggests a rethinking of how we treat dogs. By using the M.R.I. we can no longer hide from the evidence. Dogs...seem to have emotions just like us. And we must reconsider their treatment as property. [The New York Times]

As with children, the adults that take care of dogs should be considered not "owners" but "guardians," Bernas argues. And as with children, if they don't take proper care of them, the dogs should be removed and placed in safer homes. In an ideal world, writes Berns, dogs would be granted personhood, thus banning "puppy mills, laboratory dogs, and dog racing for violating the basic right of self-determinations."

But not everyone is buying the argument. Wesley J. Smith at National Review worries that if dogs are granted the same rights as a human, or a human child, it will severely limit their potential for improving the world. He writes, "If advocates like Berns get their way, we will no longer be able to make beneficial use of dogs — from pets, to guards, to research subjects, to cancer detectors, to assistance dogs that help people with disabilities."

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Moreover, Smith is unconvinced by Berns' evidence. Dogs' intelligence and positive emotions "do not make them morally equivalent to a human child," he writes. "Human exceptionalism is about far more than that!"

However, while we may not be granting dogs the same rights as humans any time in the near future, Berns' research provides substantial evidence for reevaluating our relationship not only with dogs but all living creatures. Michael Byrne at Vice writes:

If we are dealing with a planet full of other thinking, feeling machines like us rather than mere survival machines, it puts our whole strategy of manic exploitation in question. Or it should, anyhow. [Vice]

Indeed, simply reconsidering our relationships with dogs — and all animals — has its own positive potential without formalizing these rights into laws. "Terrible people will always do terrible things, but there are beliefs that enable them," writes Byrne. "And one of those is the notion that other living things are not quite as living as human beings."

Emily Shire is chief researcher for The Week magazine. She has written about pop culture, religion, and women and gender issues at publications including Slate, The Forward, and Jewcy.

-

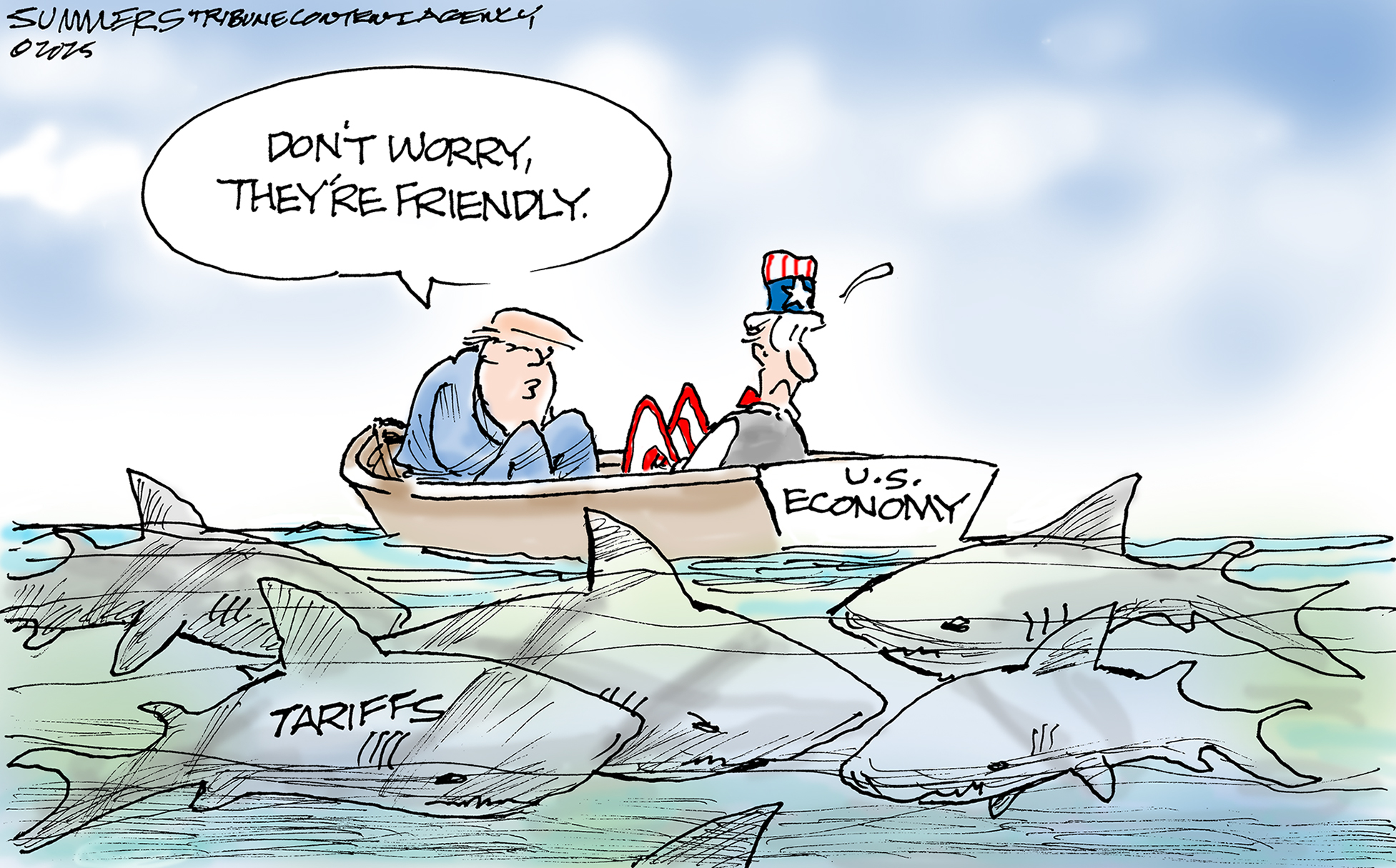

Today's political cartoons - May 11, 2025

Today's political cartoons - May 11, 2025Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - shark-infested waters, Mother's Day, and more

-

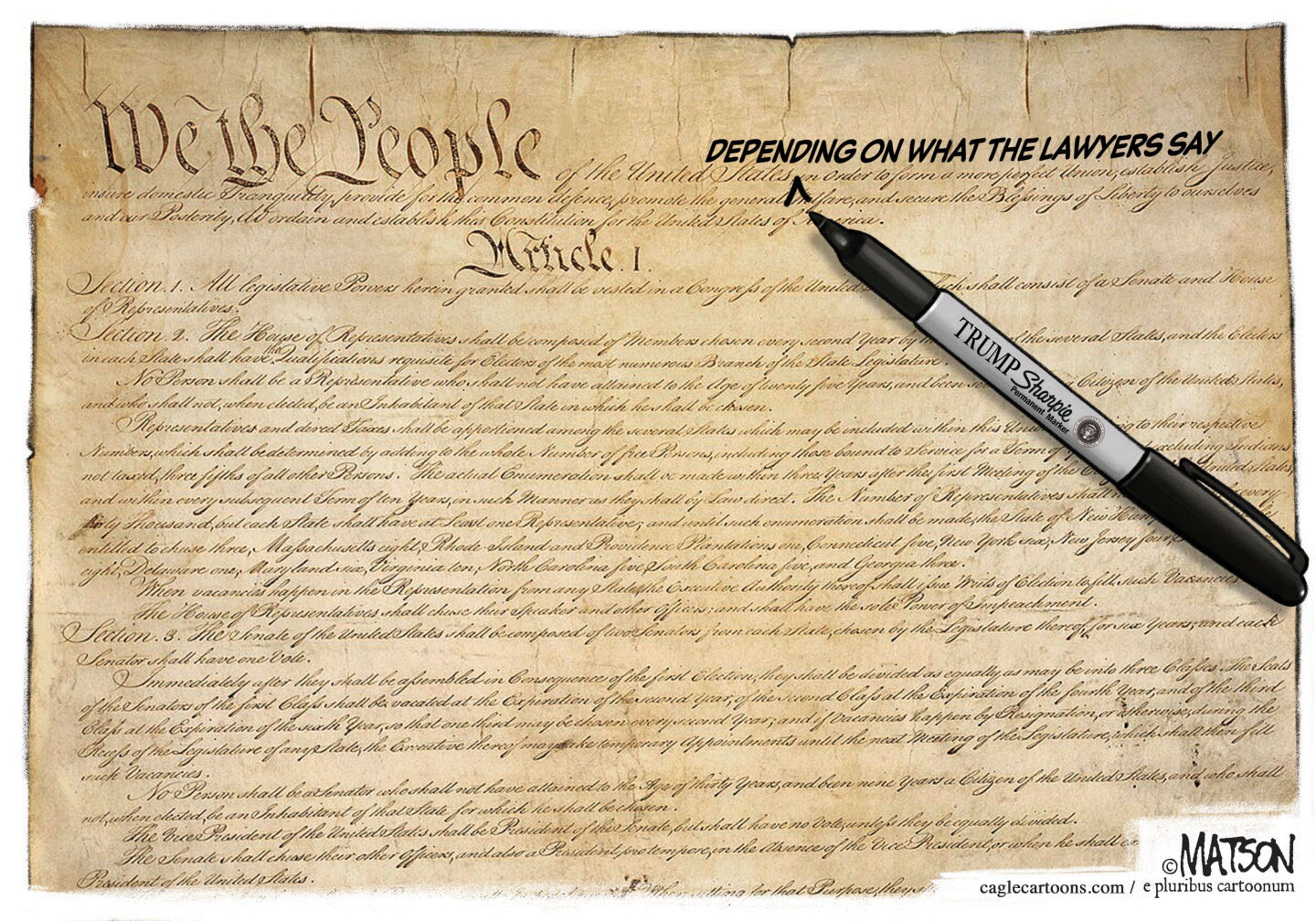

5 fundamentally funny cartoons about the US Constitution

5 fundamentally funny cartoons about the US ConstitutionCartoons Artists take on Sharpie edits, wear and tear, and more

-

In search of paradise in Thailand's western isles

In search of paradise in Thailand's western islesThe Week Recommends 'Unspoiled spots' remain, providing a fascinating insight into the past