Girls on Film: How the new Carrie fails to tell the story it should be telling

Bullying among teenage girls has never been more relevant — but Kimberly Peirce's Carrie misses the chance to tell the real story

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

To copy or not to copy — that is the undying question at the heart of Hollywood. On one level, it determines which beloved classics will get remade at all. On another, it applies to how they'll be remade: Will a film break new ground, or will it stay loyal to the original?

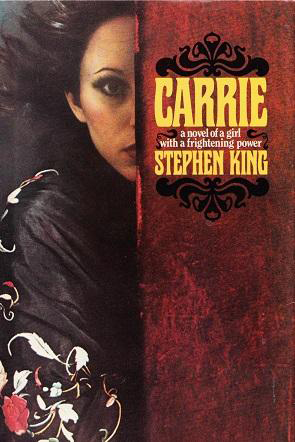

Unfortunately, Kimberly Peirce's Carrie, which hits theaters today, is the latter — a film so loyal to Brian De Palma's 1976 adaptation that it misses the social relevancy of Stephen King's original novel.

When it begins, Peirce's Carrie appears to go out of its way to distinguish itself from De Palma's Carrie. Peirce drops the original film's montage of young skin, with naked and semi-naked girls frolicking in the locker room with stereotypical slumber party abandon. Instead, as she told The New York Post, she focuses on "King's characterization of Carrie, her mother, and the girls, and to Carrie's response to being bullied."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The film opens with Margaret White's (Julianne Moore) pained scream, which breaks into a shot of a seemingly peaceful bungalow. The camera travels through the house, tracking a trail of evidence of child birth — the water that broke, the blood, the broken teacups — that lead to Margaret's bed. She's screaming, with no one coming to her aid, as she discovers that her "cancer" of the stomach is actually a child. A religious extremist convinced that sex and reproduction are evil, Margaret is sure her that her child is evil, too, but she ultimately cannot bring herself to kill the baby. And so we meet Carrie (Chloe Moretz).

But from there, the film largely adheres to De Palma's original. Carrie is tormented when she gets her first period in the shower. When her schoolmates are disciplined for their bullying, they break into two factions: Those that want revenge (with pigs' blood), and those that feel bad (Sue Snell heads straight for her do-gooder boyfriend to urge him to take the loner to prom).

The biggest change from the 1976 film to the 2013 film is how Carrie responds to the newfound telekinesis that bubbles up after her trauma in the shower. In Peirce's hands, telekinesis becomes a method of empowerment (a less-witchy The Craft), with Carrie's meekness melting away as her skills increase. Instead of an emotion-dictated explosion of power, Carrie practices and strengthens her new skill, which becomes less about panic and danger, and more about a superpower the teen must learn to control (which is no surprise, since Peirce has described this as a superhero origin story).

But it is not, as the director says, taken completely from the book rather than De Palma's movie.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The "reimagining," as Sony has branded it, doesn't return to King's source material. Instead, Glee writer Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa rewrote Lawrence D. Cohen's 1976 adaptation with minor embellishments, keeping many twists from the original film that aren't present in the novel. Margaret still warns: "They're all gonna laugh at you," and Carrie still returns home to wash herself off and have her final, more extreme, Hell-destined fight with mom. Each recognizable moment might pluck at nostalgia for the original — but it also pushes the film towards mimicry, and away from the interesting dynamics Peirce strove to accentuate.

But if Peirce and Aguirre-Sacasa had returned to the novel, magic could have struck Carrie twice.

In this treatment lies the power the remake failed to employ.

Carrie is about a girl with telekinesis whose severe ordeal leads her to deadly ends — but it is also a story of teen trauma, and how an adult society struggles to understand it. Each document included in the novel reveals a world where theory replaces fact, as the outside voices interpreting the events focus on the paranormal and not on Carrie's all-too-normal woes. The tale is decades old, but Carrie still touches on ongoing, hot-button topics like sex education, female bodies, and bullying.

Carrie and her mother are a two-tiered extreme of the dangers of abstinence-only education and bodily ignorance. Margaret considers the female body so sinful that she inflicts pain upon herself to punish her vessel of sin. Believing that sex and children are a perpetuation of evil, Margaret raises Carrie to be so ignorant about her body that the girl is certain her first period is death, much like her mother was certain that her pregnancy was cancer. Margaret refuses to let them discuss or attempt to understand their bodies and impulses, and instead, insists upon extreme piety and prayer that leave Carrie unequipped to deal with her own body and the world, making her ignorance the catalyst for destruction.

This ignorance is exacerbated by the extreme bullying she faces as an outsider. Some question the use of beautiful actresses to portray Carrie White — a girl described in the novel as a "frog among swans" and "chunky," with "pimples on her neck and back and buttocks, her wet hair completely without color." But if recent history has taught us anything, it's that beauty doesn't keep teen girls safe. Over and over, the media gets plastered with the pictures of attractive girls like Amanda Todd, Rehtaeh Parsons, and Rebecca Sedwick who took their own lives after suffering repeated bullying in school and online. It's an epidemic compounded by the teens who proudly display their bullying and assaults on social media sites, eager not only to perpetrate, but to document.

Peirce starts to tap into that in her Carrie — but unfortunately, she doesn't finish the exploration. In a culture where the Steubenville rape victim didn't know she was assaulted until she saw proof of it on social media sites, it begins to seem less absurd when Carrie's classmates laugh at her blood-covered body and the video that began the torment. It hits the carelessness that can inspire bullying, and how much easier it is for teens to go with the crowd rather than pull a Sue Snell. But the links remain nothing more than a hint of a potentially greater film, as Carrie morphs from the story of bullying to a muddled mixture of super-powered revenge and popcorn horror.

Rather than tapping into the zeitgeist that would bolster the bloody horror with that visceral tendril of reality, the film dodges it and lets the fear be superficial and familiar. If they did go back to the source, Carrie could be a whole lot more than a familiar horror film. Tapping into that cultural conversation would allow the depth that every great horror film has: The recognizable horror of real life that makes every splatter of blood feel all the more real.

"You can only push someone so far before they break," the movie warns. If Carrie truly strove to investigate what that means for us today, and not just update De Palma's treatment, who knows how much power Carrie would truly have.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day