How the Catholic Church made its peace with Charlie Hebdo

The satirical magazine began as an enemy of the French clergy. But under the aegis of Enlightenment liberalism, they found common cause.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I was brought up to hate Charlie Hebdo.

Charlie Hebdo's genesis was not as a generic humor magazine, but as a part of a specific strain of the French left, the anticlerical left, which was defined specifically by its hostility to religion and, historically, my religion, Roman Catholicism. Think of Bill Maher as a very milquetoast version of the French anticlerical left.

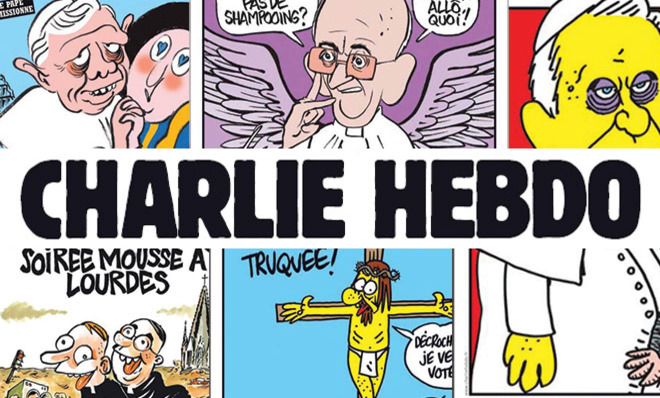

Until the Danish cartoon affair, when Charlie Hebdo began to suffer the ire of jihadism, and responded with its masterful and felicitous trolling, it was much more likely to make my faith the target of its crude attacks. Even though Charlie Hebdo lampooned everything, it had a particular interest in attacking religion as the most stupid and despicable thing on the face of the planet.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In France, the battles over separation of church and state often ended up in the streets — and often turned bloody. During the French Reign of Terror and the Paris Commune many Catholics were martyred, but even democratic governments oppressed religion. The French Third Republic for several years banned religious schools, forcing many families into exile. Catholicism lost, and France got the hard-secularist bargain that it is so well known for.

For many people in my family, Charlie Hebdo represented everything that went wrong with the country: vulgar, often for the sake of being vulgar, disrespectful of all authority, of no redeeming artistic or cultural value. The Charlie Hebdo staff and I had diametrically opposed views on religion, philosophy, politics, economics — you name it.

The attack this week on Charlie Hebdo had, at least, the virtue of being starkly revealing. Here were men brutally murdered for their service to one of the greatest ideals of civilization; here were brave men who had been threatened and attacked before, and had responded with fortitude. And we should not forget the police officer of North African descent who died protecting them, or the member of the cleaning staff, a bystander and father of two, also murdered. They symbolize the indiscriminate character of Islamic terrorism, as well as the fact that jihadis are perfectly willing to kill their fellow Muslims, who are their most numerous victims. Here was everything good and civilized in the world, attacked by everything base and depraved.

And even before the attack, Charlie Hebdo's cartoonists had shown their redeeming qualities: They were funny, and they were good. They trafficked in a French kind of Rabelaisian humor that doesn't carry well in foreign cultures, certainly not in the Anglosphere. When snooty British journalists make a point of talking about the crudity of their cartoons, I want to say that they are the ones being vulgar, on top of being humorless — and I don't know which is worse.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When their cover depicted Benedict XVI resigning from the papacy to elope with a Swiss guard, I had to laugh. And their post-firebomb cover showing a cartoonist droolingly French-kissing a mullah was, perhaps, the most genius act of trolling in recent history.

But that is not why an attack against them is an attack against everything I hold dear. They represent everything I aspire to: freedom, courage, not to mention a big helping of whimsy.

I am not alone. Right after the attack, André Cardinal Vingt-Trois, archbishop of Paris, sent a message of dismay and support for Charlie Hebdo's right to mock his faith. A century ago, the cardinal's predecessor would undoubtedly have thought that Charlie Hebdo should be shut down as a measure of public safety. And a few centuries before that, his predecessor might have put Charb or Cabu on the rack.

It was not by virtue of a shared Christian faith that Charlie Hebdo's staffers and I were brothers — it was by virtue of our shared faith in Enlightenment liberalism. And not very long ago, my church might have asked me to commit the injustice of denying their rights.

At the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church recovered what I believe to be the more authentic Christian teaching, accepting religious freedom and pluralism. But let's face it: the Catholic Church fought liberalism, and lost. I love the Catholic Church more than anything in the world, and I hope I would die for her if I had to — but I am glad she lost.

Charlie Hebdo reminded me that as much as I am a man of Christ and a man of the church — because I am these things — I am also a man of Enlightenment liberalism. That is why I see an attack against people with whom I disagree on almost everything as an attack on my values, on what I believe in and cherish.

That is the value system that any civilization worth cherishing must incorporate — and that is the value system that we must defend against these jihadi barbarians.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.