America doesn't trust its experts anymore

From climate change to medicine to religion, everyone's an expert — except people who disagree with us. So what?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's never been a better time to be a media-savvy expert in America, it seems. Cable networks want to put you on TV, publishers want to give you a book deal, and newspapers desperately want your quote. The only thing missing? Actual clout.

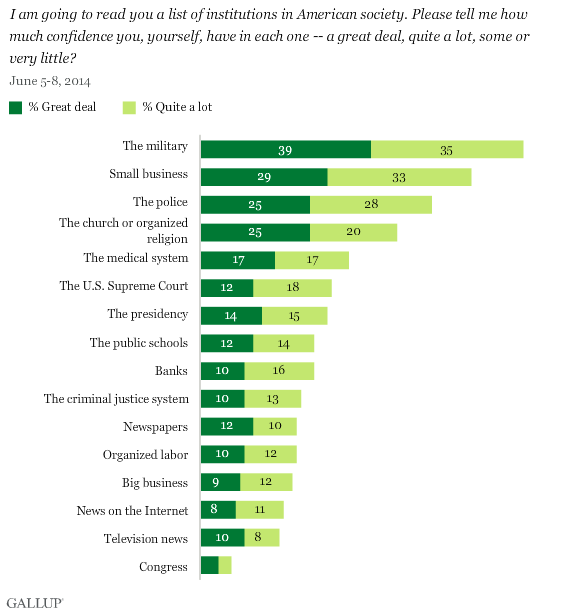

Doctors, judges, physicists, and priests used to be figures of towering authority in the U.S. Gallup's June survey of public trust in some high-profile professions has some sobering numbers for America's expert class:

Only three institutions top 50 percent — the military, small businesses, and the police. The military's numbers have been generally rising since the end of the Vietnam War, if you look at Gallup's historical numbers, but most of the institutions are more in line with organized religion:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, polls are an imperfect yard stick to measure public trust in expertise, and "organized religion" is not the same as your pastor, nor is a doctor "the medical system." (The family doctor is actually pretty trusted these days.) But I don't think it's too controversial to suggest lots of Americans believe that, given 15 minutes and a Wikipedia article, or a short segment compiled and edited by the (not very trusted) TV news, they are expert enough to have a strong opinion about a given topic, with a high degree of confidence that their opinion is correct.

But here's where things get interesting, and potentially sticky: If these people are challenged by an actual expert — someone who has studied said topic for years or decades — they probably wouldn't change their opinion. In a series of famous studies in 2005 and 2006, University of Michigan researchers showed accurate news stories to people who believed a demonstrably incorrect version, and it rarely changed their minds. Quite the opposite. "Facts, they found, were not curing misinformation," Joe Keohane explained in The Boston Globe. "Like an underpowered antibiotic, facts could actually make misinformation even stronger."

A more recent study, published in the journal Pediatrics last December, found that parents who opposed vaccinations were unswayed by four different presentations about the low risks and high rewards of vaccines. "None of the interventions increased parental intent to vaccinate a future child," the researchers wrote. The decision not to vaccinate can have real-life, sometimes fatal consequences for more than just the family that opts out.

Where mistrust in experts is probably of most consequence, however, is climate change. Now, the numbers on this aren't as tilted away from the experts as you might think, given the tenor of the political debate. In March, Gallup reported that 57 percent of Americans believe that pollution and other human activities are making the Earth warmer, versus 40 percent who blame natural causes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's not as high as the 97 percent of climate scientists who subscribe to human-influenced climate change, but it's pretty good considering that 89 years after the Scopes Monkey Trial and 155 years after Charles Darwin published On the Origins of Species, a plurality of Americans — 42 percent — believe that "God created humans in present form." A 2009 report from Pew found that, once again, 97 percent of scientists agreed that "humans and other living things have evolved over time" (though 8 percent of them also agreed that "a supreme being guided the evolution of living things for the purpose of creating humans and other life in the form it exists today").

The numbers in these two examples show pretty stark partisan differences — on climate change, for example, 41 percent of Republicans and 79 percent of Democrats sided with human-affected warming. But mistrust in experts, even scientific experts, isn't just a conservative/Republican thing. Plenty of parents opting out of vaccinations (despite the overwhelming consensus of public health experts) and public school (taught by well-trained educators) are liberals, and liberal-tarian Portland, Oregon, keeps on voting down fluoridating its drinking water.

Mistrust in experts can be a serious problem — on climate change, for example, Congress obviously won't act unless it absolutely has to. More than 6 in 10 Americans have to believe action is necessary.

But it's complicated. America has more "experts" than ever — universities are churning out more Ph.D's than academia can employ, and each newly minted doctor of philosophy (or medicine or law) has specialized in some narrow subject. Plus, think tanks are cultivating their own cadres of experts. Everyone is trying to get their experts on TV and in print. And TV networks employ their own stables of questionable experts, sometimes hired more for their entertainment value or politics than their credentials.

It's healthy to question authority, but we need actual experts. The brilliance of the Fox News motto, "We report, you decide," is that it encourages our vanity that we can know as much as anyone else, we can be experts, given a stream of carefully curated facts and opinion. MSNBC, which has a similar business/editorial model, is stuck with the less-empowering "Lean Forward."

There are a number of ways forward for expertise in America. We can become increasingly mistrustful of scientists, doctors, professors, bureaucrats, bankers, and other experts in their fields; or we can find a better way to filter out the would-be experts spreading misinformation; or we can continue disregarding all experts who don't confirm what we already believe. Perhaps we'll all suffer because we didn't heed our experts, or perhaps our experts will win back our trust.

In the end, how much does our skepticism of expertise really matter? Don't ask me — I'm an expert in writing, not social science. I report, you decide. Bob Dylan, expert songwriter, implicitly pooh-poohs expertise in "Subterranean Homesick Blues" (1965): "You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows." But as for me, I'd check with a meteorologist before planning an outdoor party.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie