The progressive case for ending the minimum wage

It's a 20th-century solution for a 21st-century problem

The New York Times argues that the U.S. should follow Germany's lead in adopting a significantly higher minimum wage. Germany — which did not previously have a minimum wage, and instead relied on bargaining between employers and unions — recently passed legislation that will set a nationwide minimum wage at 8.50 euros an hour, effective in 2015.

Germany's new minimum wage is roughly $11.60 — significantly more than America's federal minimum wage of $7.25, and more even than Democrats' target of $10.10. And the Times concludes: "Germany's move offers the United States important lessons, if only lawmakers in Washington would learn."

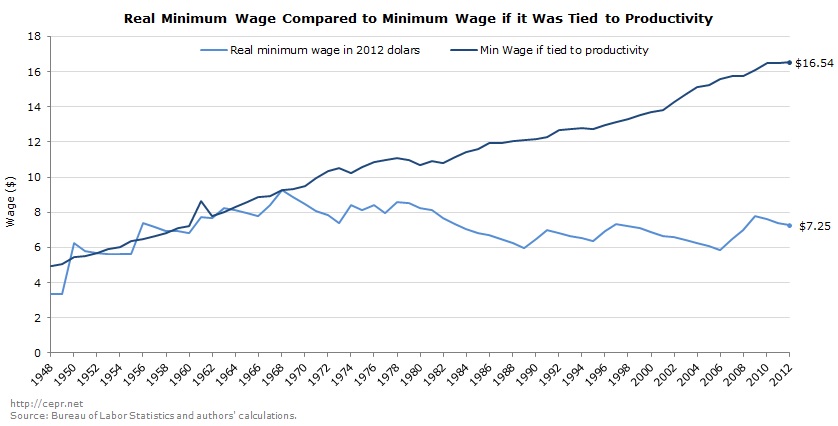

Now, there's no doubt that those who want to hike the minimum wage in the U.S. have the right intention. In the last 40 years, the minimum wage has totally failed to keep pace in the U.S. with worker productivity:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(Bureau of Labor Statistics/CEPR)

The blame for that can legitimately be laid at the feet of politicians, who have failed to deliver a minimum wage that properly compensates workers for their productivity or assures a decent standard of living for low wage workers. Corporate revenues — instead of going to workers — have accrued in corporate profits, which are at all-time highs both in nominal terms and as a percentage of the economy.

But although a higher minimum wage might have been helpful during the last 40 years, going forward, the minimum wage is not the answer.

Traditionally, opponents of the minimum wage have argued that if labor costs are set too high, jobs will simply go elsewhere. And to some extent, that is true. That's why we have seen, in general, a shift in manufacturing jobs from North America to Southeast Asia, where labor costs have been much lower. But cities (like San Jose, San Francisco, and most recently Seattle) can still set a high minimum wage and have a robust economy with lots of jobs, because even with high labor costs employers still want to set up shop where all the economic action is. Higher labor costs are just factored in as another cost of operating in a city, like the higher rents businesses pay for a built-up location.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As I've argued before, what's changing is the emergence of robotics and the automation of an increasingly large number of professions. Robots have already taken over many roles in manufacturing and are now moving into offices and the service economy: Roles including food servers, bank tellers, telephone operators, receptionists, mail carriers, travel agents, typists, journalists, telemarketers, and stock market traders.

And while there are sure to remain lots of jobs that can't be replaced with a robot — including personal assistants, janitors, home health aides, and security personnel — and while many new human professions will likely emerge in time, the automation revolution is already reducing employment. As the pace of technological progress in fields such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and machine learning continues to increase, the displacement of human labor will continue in tandem.

How big will this be? One recent study indicated that 80 percent of all current jobs can be automated in coming years. It's going to be a whole new industrial revolution.

That's not the fault of the minimum wage — it's the fault of increasing innovation, technological change, and human genius. But what it means is that the minimum wage is not the right tool for the job. When mass human labor was the predominant source of economic activity, the minimum wage was an effective tool — the economic growth of the 1950s and 1960s was built on widespread economic prosperity and a much higher real minimum wage.

But when you can so easily replace a human with a machine or a robot, the minimum wage becomes more of a hindrance than a help. You can't help an increasingly large number of people displaced by the new industrial revolution through a higher minimum wage.

So I think Germany has got this all wrong, and The New York Times is advocating a 20th-century tool for a 21st-century problem.

As I've argued before, it would be much smarter and more forward-thinking to implement a basic income — either a so-called negative income tax, or a universal income. In other words, taxing the owners of the robots to support the people who are put out of work by them. People can use that money to do whatever they like — start their own business, travel the world, pursue a hobby, learn how to program robots.

But we won't get there while policymakers and journalists are still stuck on 20th-century solutions. Yes, it is hard to imagine a world where work is no longer a moral expectation — as it has been for most able-bodied people throughout history — but a choice.

But in a world where robots do the vast majority of the necessary work, and where human labor is no longer the critical ingredient for productivity that it once was, we will have to face these moral conundrums sooner or later.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

6 products and apps to help fight jet lag

6 products and apps to help fight jet lagThe Week Recommends Don't let travel fatigue drag you down

-

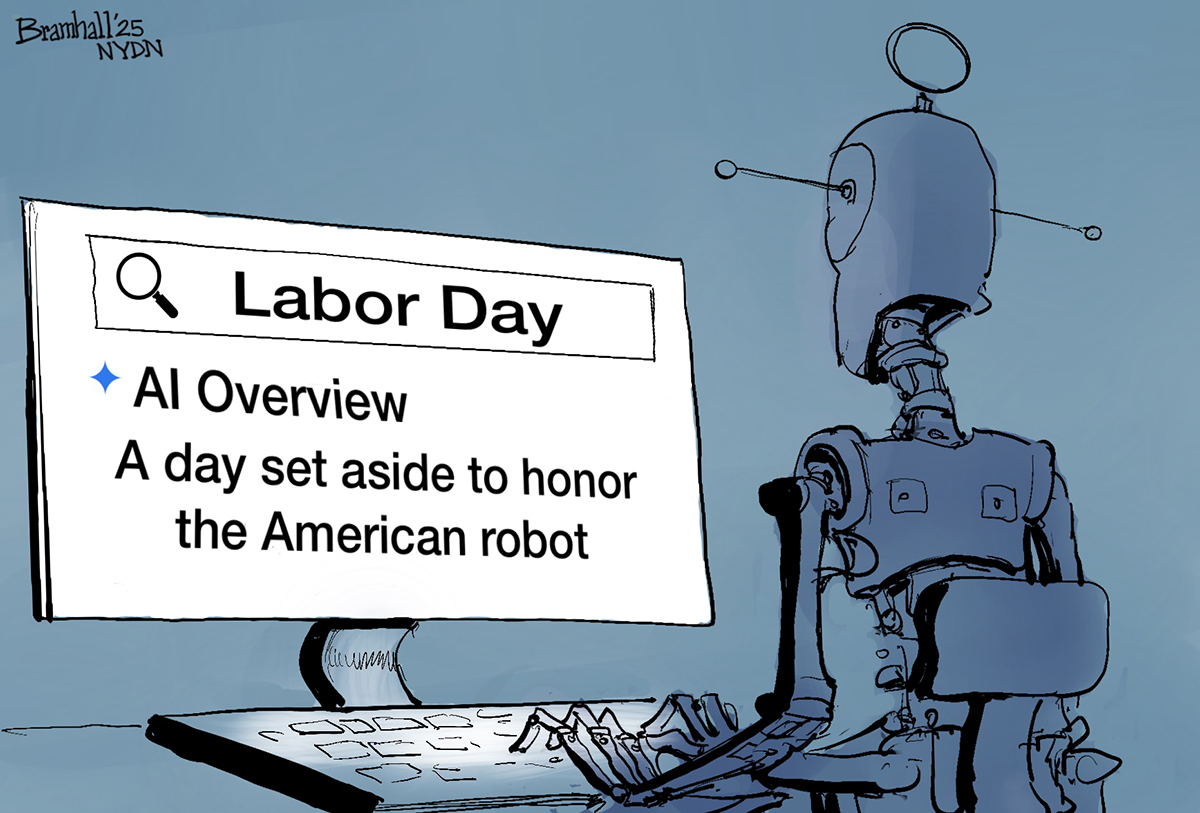

September 2 editorial cartoons

September 2 editorial cartoonsCartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include Labor Day redefined, an exodus from the CDC, and Donald Trump shouting down rumors

-

The trial of Jair Bolsonaro, the 'Trump of the tropics'

The trial of Jair Bolsonaro, the 'Trump of the tropics'The Explainer Brazil's former president will likely be found guilty of attempting military coup, despite US pressure and Trump allegiance