Girls on Film: The troubling reason Hollywood keeps failing female filmmakers

"Let's just really make a change or never, ever speak of it again," Punisher: War Zone director Lexi Alexander tells TheWeek.com.

When I began writing this column nearly five years ago, there wasn't much media interest in the status of women in Hollywood. In the years since, the tide has changed. A quick Google search will turn up countless pieces on the issue: The continually abysmal statistics published each year; the glass ceiling that Kathryn Bigelow's historic Oscar win failed to break; and, most commonly, the ever-prevalent question, "Where are all the women? Where are all the women-directed films?" But in a recent, incendiary blog post, director Lexi Alexander argued that all those well-meaning stories have been asking the wrong question.

The real question, in other words, should be "Why isn't anyone actually trying to solve this problem?"

After years of what Alexander calls "blissful ignorance" on Hollywood's issues with gender discrimination, she finally decided to speak out this month in a blog post titled "This Is Me Getting Real" — an account of her frustration with the superficial media pieces written about Hollywood's problems, and the industry's own laziness when it comes to solving them. It's a piece that comes just as Dr. Martha Lauzen's latest Celluloid Ceiling statistics revealed that there has been no progress made for women in the industry in 16 years, and that many areas have actually seen a decrease in inclusiveness.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In a recent conversation with The Week, Alexander elaborated on her post. "My breaking point was the endless coverage of gender inequality in Hollywood by the media that turned into white noise for the parties responsible, as well as the hypocrisy of people who are supposedly working on achieving parity," she said. "Nobody in the media asks the questions that matter. We can spend another 35 years wailing about the lack of women at the Oscars. I can see the headline now, 'Oscars 2049: Where are the women?' Let's just really make a change or never, ever speak of it again."

Alexander's piece specifically singles out the Director Guild of America's Women's Steering Committee, which has held a long string of fruitless meetings dedicated to solving the imbalance that everyone agrees is "embarrassing" (but no one has actually fixed). Her recollections from the two meetings include:

- A woman stating to fellow female filmmakers: "Let me make this very clear: I am not here as one of you, I am one of the boys, okay?"

- A catch-22: Studios blame the DGA for the lack of female members, who point out that women need to get hired to be eligible for the DGA.

- A collective confusion over what should be done, other than a semantic decision to change the terminology around diversity hiring from "best efforts" to "work diligently."

In fact, there has been no meaningful improvement in gender diversity since before 1978, the year a progress report (which Alexander links to in her piece) on the issue was released by the California Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. The report noted that the Department of Justice had found in the '60s that discrimination existed in the film industry, violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Though the Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees had "denied the existence of discrimination or discriminatory conduct," they agreed to a settlement in 1970 to avoid litigation.

But that private settlement didn't exactly make major strides toward solving the problem. It was voluntary and had "no enforcement procedures or penalties for noncompliance," said the report eight years later. It was victim of staff shortages that made it difficult to monitor compliance. Provisions made to stop preferential treatment for "friends and relatives of union members," and to create training programs and equal opportunities, lacked the pressure of actual enforcement. And, much like Alexander's description of today's catch-22, the 1978 report states: "Union representatives disclaim responsibility for the few minorities and women on the rosters, saying that rosters are run by the employers and one must be hired by an employer in order to attain roster status."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Eight years after the settlement, the report notes, many studios were only just starting to create the policies outlined — defying not only the earlier agreement but also regulations spelled out by the U.S. government. As the report states, "all major studios had Federal contracts in excess of $50,000 during 1975 and 1976," and if a contractor didn't have "complete written affirmative action plans within 120 days of signing a Federal contract for $50,000 and over, that contractor is in violation of Federal regulation." As the report itself describes, studios were just starting them in 1976-78.

Director Maria Giese, writing for IndieWire, has since filled in what happened next. In 1979, the DGA had created the Women's Steering Committee, and six of its first members (the "Original Six") began looking at statistics with help from the national executive secretary of the DGA, Michael Franklin. Multiple meetings were set with studios, they circulated reels, and nothing happened. "These meetings were based only on voluntary compliance and went on for a year with negligible results," Giese writes.

When one particular meeting passed with no studio executives in attendance, Franklin launched a class-action lawsuit against three studios in 1983. Unfortunately, though Judge Pamela Rymer supported the validity of their claims, they couldn't get class-action status if the suit was led by the guild — a conflict of interest — and not surprisingly, the women didn't have the financial means to back it alone.

But even without legal success, something remarkable happened: Women's involvement in Hollywood finally started to increase. "Just 10 years later," Giese writes, "TV episodes directed by women had risen from 0.5 percent to 16 percent." But further action and enforcement ended there, and those numbers have since decreased. Moreover, as committees argue about how to advance women in Hollywood, the latest contract places women under the umbrella of "diversity," which means that studios can "continue to advance diversity without advancing women."

And there lies the conundrum Alexander reluctantly addresses. If, historically, studios only promote active change when forced to — and 35 years of seemingly well-intention activism failed to change anything — can the situation improve without affirmative action?

Alexander told us:

If I am very selfish, then yes, I am concerned my own efforts could be diminished by a quota campaign. But that was exactly my point of the blog. Just because I like difficult odds doesn't mean they're fair, and just because I'm not a fan of quota hirings personally does not mean it's not necessary. It's not about me, you, or anyone individually. It's about the bigger f--king picture. Look, at the rate we're going right now, we'll have zero percent of films directed by women in about four to five years. It is time to stop talking and start doing. And drastically. [The Week]

Despite the difficulties for women in the industry, Alexander herself has thrived. As a former karate champion from Germany who immigrated to the U.S., Alexander quickly worked her way up from stuntwoman to Oscar-nominated director with one of her first films, the short Johnny Flynton. She has helmed feature films including Green Street Hooligans, which won the South by Southwest jury award. Since Patty Jenkins was kicked off the director's chair at Thor: The Dark World, Alexander is also the closest Hollywood has gotten to a woman helming a mainstream superhero film with her anti-hero Marvel property, Punisher: War Zone.

Alexander explains her realization:

What many people don't know is that until last year, I was still somewhat of a denier when it came to gender discrimination. My enlightenment did not occur through my own experience and due to my own career. I saw the light when I wrote a script for an actress friend of mine, about a female computer scientist. [The Week]

Seeing the discrepancies elsewhere caused her to focus on her own profession and ultimately, speak out. She told us:

As I said in my blog, if people would have just been honest and stated that they have no interest in gender balancing, or if they would have simply kept quiet — given that the message is utterly clear — then I don't think I would have ever spoken out. Having been an athlete, impossible odds are the more satisfying achievements, and certainly the more interesting journeys. In the bigger picture of life, if I have to be 10 times as good, 10 times as creative as a man, then getting to work on that is not a waste of time. The fairness of it is a different question. Boy, oh boy, hypocrisy just makes my blood boil. Every time a showrunner says we tried to find more female directors but there were none, I have Ally McBeal-type fantasies of cranes scooping them up and dropping them in garbage bins. I think bullshitting somebody straight in the face is worse than spitting at them, frankly. [The Week]

In her blog, Alexander asks: "If diversity hiring would be a sincere core value to Hollywood's studios, do you honestly believe they'd fail?" This is the heart of the issue. People have expressed shock over the imbalance for over 30 years — but in 2014, there is no real change.

For all of the problematic stigma associated with it, affirmative action is also something — as Alexander astutely points out — that may have benefits beyond upping the numbers. She says:

Mentorship is a major roadblock. Men feel more comfortable mentoring young males. Hollywood has quite a sleazy reputation, and I know that some men fear that mentoring a woman, especially if she is younger — which up and coming directors tend to be — could make the wrong impression....

If there was any kind of serious, official gender balance campaign, executives could fight for female directors under the shield of that campaign, and not worry about the impression he'd leave with his higher ups about why he is going out of his way to give this female director a break.... I had identified this issue on my own, and I wasn't sure if I was just imagining it or if this was really happening. Then a civil rights attorney explained to me that it is not only a major issue, but also one that has been long identified with studies and statistics in the law profession. [The Week]

Alexander rightly questions how women can pick up this slack considering not only the proclamations of being "one of the boys," but also the status of the industry:

Two of the most 'successful' female directors have recently spoken out — not in the way I did, but still, it was loud and clear if you were open to hear it — that despite their success, they're struggling like they did on day one. So, in that space of mind, what kind of mentor can you be? [The Week]

Of course, the issue doesn't begin and end with Alexander's point of view, and there are a number of aspects to consider. But she isn't purporting to have an all-inclusive view. Her blog is a rallying cry asking journalists to dig deeper and discuss the problems with the superficial inquiry and observational think-pieces that have left the problems at a standstill. "I would love, love, love to be wrong about this," she says.

But the simple fact is that there has been no real advancement for women in decades. It isn't a case of invisibility, but an entire system that needs to be jolted out of the status quo — one that extends well beyond whether a woman is "right" for a gig, or can ever get the experience studios want for a job.

Gender discrimination in Hollywood goes far beyond women simply not getting the gig," Alexander blogged. "It is reflected in movie budgets, P&A budgets, size of distribution deals (if a female director's movie is lucky enough to score one), official and unofficial internship or mentorship opportunities, union eligibility, etc., etc., etc....

Truth: I loathe the idea of being hired because of my gender, and I shudder at the thought that one day I show up on set and half of the crew thinks "here comes the quota hire." [Lexi-Alexander.com]

But it won't have to come to that if the conversation about women in Hollywood stops being theoretical and starts getting active — and if we, in talking about the issue, move beyond speculation and get to the real heart of the issue.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

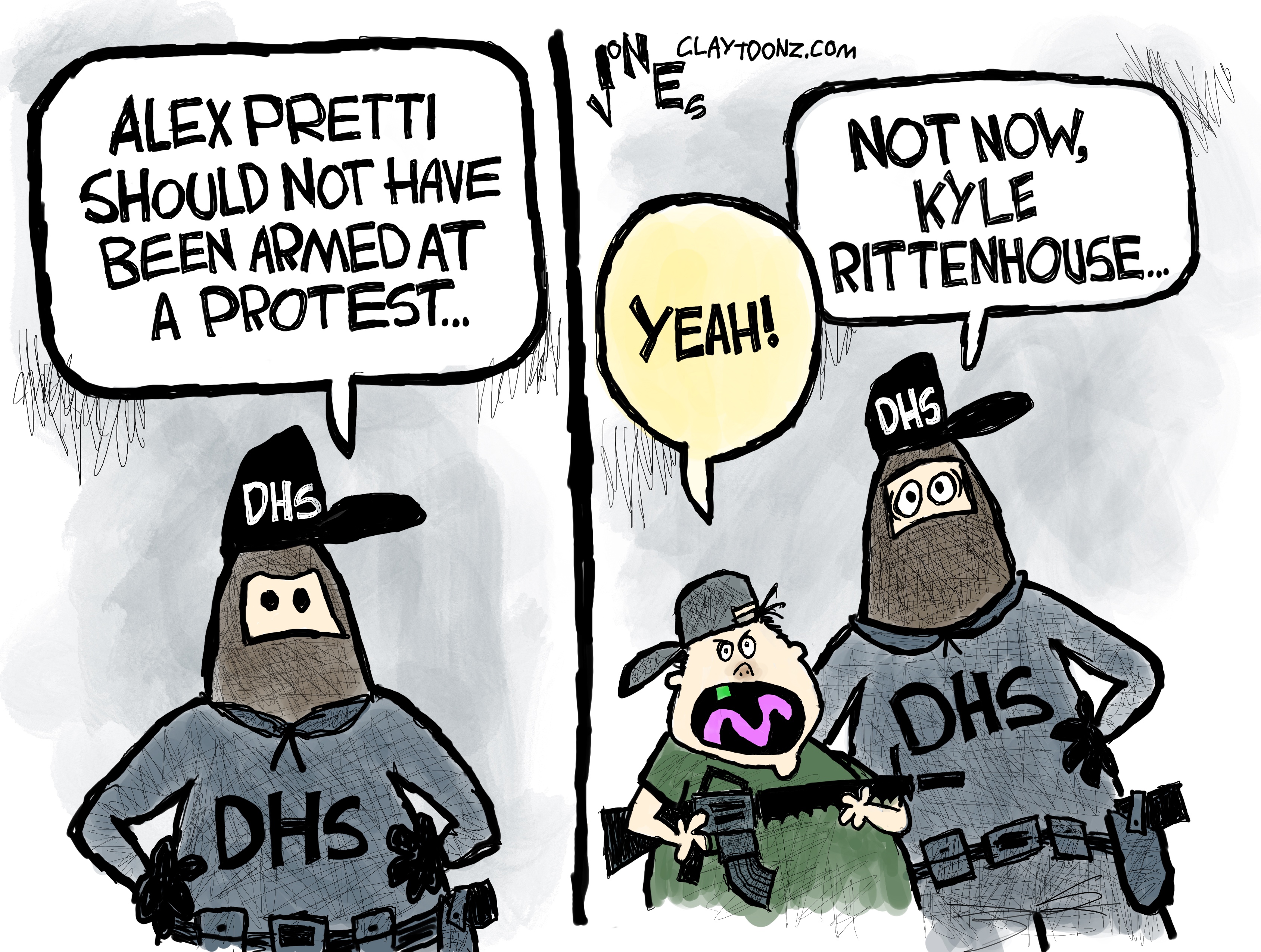

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more