5 best non-fiction books of the year

Critics hailed these authoritative histories and true-life tales as the most outstanding of 2010

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The non-fiction books that earned acclaim in 2010 explored a wide range of topics, from Cleopatra to Wall Street. For a shortcut through the forest of year-end critics' recommendations, here is an aggregated list based on the top picks of 14 publications, from The New Yorker to Publisher's Weekly:

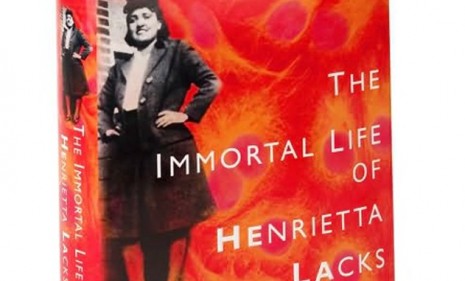

1. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

by Rebecca Skloot

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(Crown, $26)

Rebecca Skloot's dynamic book begins in 1951, in the moments before Henrietta Lacks, a poor mother of five, dies of cervical cancer, said Christine Wicker in The Dallas Morning News. In the "colored ward" of Johns Hopkins charity hospital, a research doctor cuts a sample of cancerous tissue from her body without her consent, and for reasons no one understands, the cancer cells begin to flourish. The "HeLa cells," as they've become known, now "number in the billions," and they've been critical to scientific discoveries from the polio vaccine to the mapping of the human genome. "Close to 25 years passed before the Lacks family had a clue" about the afterlife of Henrietta's cells, said Karen R. Long in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. To tell their story, Skloot spent a decade with Lacks' descendants documenting their attempts to have her contribution recognized. The result is a morally complex story "different from any you have read."

A caveat: Skloot's narrative skips around so much, it's "hard to keep track" of which events happened when, said Drew DeSilver in The Seattle Times.

2. The Possessed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

by Elif Batuman

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $15)

"It's not often that one laughs out loud while reading a book of literary criticism," said Heller McAlpin in The Christian Science Monitor. But you will while reading Elif Batuman's. In "seven delightfully quirky essays that combine travelogue and memoir with criticism," the young Stanford Ph.D. takes us on "an unconventional odyssey through the world of Russian literature," a place she obsessively turned to, she writes, in search of answers to "the riddle of human behavior and the nature of love." The Possessed is an "odd and oddly profound little book," said Dwight Garner in The New York Times. Ostensibly about Russia's legendary writers, it's actually about "a million other things: grad school, literary theory, love affairs, even how to choose a nice watermelon in Uzbekistan." Fundamentally, it's a wry, whimsical, and thoroughly enjoyable examination of the ways we relate to the stories that move us.

A caveat: Some of Batuman's passages reek of "the self-important posing of graduate students," said Bob Blaisdell in the San Francisco Chronicle.

3. The Big Short

by Michael Lewis

(Norton, $28)

"If you read only one book about the recent financial crisis, let it be The Big Short," said Steven Pearlstein in The Washington Post. Michael Lewis doesn't try for a comprehensive analysis of all Wall Street's misdeeds. Instead, he focuses on a small cast of misfit hedge-fund managers and bond salesmen who "were among the first to see the folly and fraud behind the subprime fiasco, and to find ways to bet against it when everyone thought them crazy." At first glance, "there's almost nothing sympathetic" about Lewis' main characters, said Felix Salmon in BarnesandNobleReview.com. The creators of credit-default swaps—bets that paid big when subprime mortgage bonds went bad—they could be seen as having helped fuel the problem. But Lewis uses his first-rate reporting skills to demonstrate who the real enemies were, and in so doing, he creates what may be "the single best piece of financial journalism ever written."

A caveat: Lewis treats his "brilliant oddballs" as heroes, said Hugo Lindgren in New York. "But should we?"

4. The Warmth of Other Suns

by Isabel Wilkerson

(Random House, $30)

Isabel Wilkerson's "monumental reinterpretation of the Great Migration demonstrates how history can be transformed by the way we frame its stories," said Laura Miller in Salon. Wilkerson has written as definitive a work as exists about the period from 1915 to 1970, when 6 million black Americans abandoned the South for cities North and West. After interviewing some 1,200 one-time migrants, the author focused on three, describing "both the oppressive conditions they endured below the Mason-Dixon Line and the dreams they pursued in the storied cities above it." Wilkerson has done for the Great Migration "what John Steinbeck did for the Okies in The Grapes of Wrath," said John Stauffer in The Wall Street Journal. Most important, she buries the myth that the new migrants destabilized northern cities by bringing "unemployment and poverty with them." Her evidence shows they were a stabilizing force in the cities they adopted as their new homes.

A caveat: Wilkerson shortchanges the Great Migration's economic causes, said David Oshinsky in The New York Times.

5. Cleopatra: A Life

by Stacy Schiff

(Little, Brown, $30)

Who knew there was so much more to learn about "the most famous woman in the ancient world?" said Wendy Smith in the Los Angeles Times. Cleopatra has been a captivating figure for centuries, inspiring both the greatest female role Shakespeare ever created and one of Hollywood's "most notorious" big-budget disasters. But as historian Stacy Schiff shows us in 400 pages of singing prose, we barely knew her. The true Egyptian queen was no Elizabeth Taylor. Though she used sex to ensnare some of Rome's most powerful men, she did so not for personal fulfillment but as a tactic to preserve her empire's autonomy against the push of a more powerful neighbor. Schiff "injects the queen with a complexity and humanity" we've never known, said Lisa Orkin Emmanuel in the Associated Press. She was, as Schiff writes, "a remarkably capable queen—a strategist of the first rank."

A caveat: Short on primary sources, Schiff too often just speculates, said Susannah Cahalan in the New York Post.

How the books were chosen: Rankings are based on end-of-year recommendations published by The Atlantic, The Christian Science Monitor, the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, The Economist, the Los Angeles Times, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Publishers Weekly, Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, Slate, Time, and The Washington Post.

-

Switzerland could vote to cap its population

Switzerland could vote to cap its populationUnder the Radar Swiss People’s Party proposes referendum on radical anti-immigration measure to limit residents to 10 million

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry