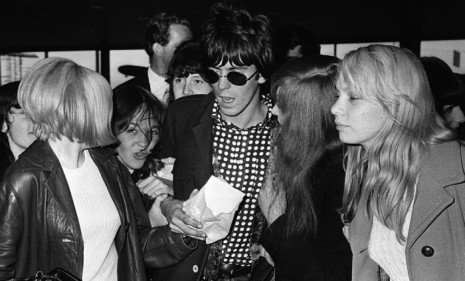

Keith Richards: The year girls went mad

In his new memoir, the veteran rocker recalls the terror of early Rolling Stones-mania

THE ARMIES OF feral, body-snatching girls began to emerge in big numbers about halfway through our first U.K. tour, in the fall of 1963. That was an incredible lineup: the Everly Brothers, Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Mickie Most. We felt like we were in Disneyland, or the best theme park we could imagine. We used to hang from the rafters in the Gaumont and Odeon theaters to watch Little Richard, Bo Diddley, and the Everlys at work. There was that amazing feeling of wow, I’m actually in a dressing room with Little Richard. One part of you is the fan, “Oh my God,” and the other part of you is “You’re here with the man and now you better be a man.”

The first time we went up on that first stage, at the New Victoria Theatre in London, it went to the horizon. The sense of space, the size of the audience, the whole scale was breathtaking. We just felt so puny up there. Obviously we weren’t that bad. But we all looked at one another with shock. And the curtain opened and aaagh—working the Coliseum. You get used to it pretty quick, you learn. But that first night I felt so miniature. And of course we’re not sounding like we usually are, in a small room. Suddenly we’re sounding like tin soldiers. There were so many things to learn, real quick. We were probably disastrously horrible in some of those shows, but by then there was a buzz going on. The audience was louder than we were, which certainly helped. Great background vocals of chicks screaming.

I was never that confident about my own playing, but I knew that between us we could do things and that there was something happening. We started off opening the show, and then we got to ending the first half, and then we got to opening up the second half, and within six weeks, the Everly Brothers were virtually saying, Hey, you guys better top the bill. Within six weeks. Something happened as we were going round England. The chicks started screaming. It was teeny-boppers! And to us, wanting to be “bluesmen,” this was, well, we’re really going downhill here. We don’t want to be some f---ing ersatz Beatles. S--t, we’ve worked hard to be a very, very good blues band. But the money’s better, and suddenly with the size of the audience, like it or not, you’re no longer just a blues band, you’re now what they’re going to call a pop band, which we despised.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

THE POWER OF the teenage females of 13, 14, 15, when they’re in a gang, has never left me. They nearly killed me. I was never more in fear for my life than I was from teenage girls. The ones that choked me, tore me to shreds, if you got caught in a frenzied crowd of them—it’s hard to express how frightening they could be. You’d rather be in a trench fighting the enemy than to be faced with this unstoppable, killer wave of lust and desire, or whatever it is—it’s unknown even to them. The cops are running away, and you’re faced with this savagery of unleashed emotions.

In a matter of weeks, we went from nowhere to London’s crowning triumph. The Beatles couldn’t fill in all of the spots on the charts. We filled in the gaps for the first year or so. You can put it down to Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” You knew it, you sniffed it in the air. And it was happening fast. The Everly Brothers, I mean, I loved them dearly, but they smelled it too, they knew something was happening, and as great as they were, what are the Everly Brothers gonna do when there’s suddenly 3,000 people chanting, “We want the Stones. We want the Stones”? It was so quick. We knew that we’d set something on fire that I still can’t control, quite honestly.

All we knew was that we were on the road every day of the week. Maybe a day off here and there to get somewhere else. But we could tell from on the street, all over England and Scotland, Wales. Six weeks ahead you could feel it in the air. We got bigger and bigger and it got more and more crazy, until basically all we thought about was how to get into a gig and how to get out. The actual playing time was probably five to 10 minutes at max. In England for 18 months, I’d say, we never finished a show. The only question was how it would end, with a riot, with the cops breaking it up, with too many medical cases, and how the hell to get out of there. The biggest part of the day was planning the in and the out. The actual gig you didn’t even get to know much about. It was just mayhem. We came there to listen to the audience! Nothing like a good 10, 15 minutes of pubescent female shrieking to cover up all your mistakes. Or 3,000 teenage chicks throwing themselves at you. Or being carried out on stretchers. All the bouffants awry, skirts up to their waists, sweating, red, eyes rolling. On the set list, for what it was worth, we had “Not Fade Away,” “Walking the Dog,” “Around and Around,” “I’m a King Bee.”

We used to play “Popeye the Sailor Man” some nights, and the audience didn’t know any different because they couldn’t hear us. So they weren’t reacting to the music. The beat, maybe, because you’d always hear the drums, just the rhythm, but the rest of it, no, you couldn’t hear the voices, you couldn’t hear the guitars, totally out of the question. What they were reacting to was being in this enclosed space with us—this illusion, me, Mick, and Brian. The music might be the trigger, but the bullet, nobody knows what that is. Usually it was harmless for them, though not always for us. Amongst the many thousands a few did get hurt, and a few died. Some chick third balcony up flung herself off and severely hurt the person she landed on underneath, and she herself broke her neck and died. Now and again s--t happened. But the limp and fainted bodies going by us after the first 10 minutes of playing, that happened every night. Or sometimes they’d stack them up on the side of the stage because there were so many of them. It was like the Western Front. And it got nasty in the provinces—new territory for us. Hamilton in Scotland, just outside Glasgow. They put a chicken wire fence in front of us because of the sharpened pennies and beer bottles they flung at us—the guys that didn’t like the chicks screaming at us. They had dogs parading inside the wire.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

One night somewhere up north, it could have been York, I remember walking back out onto the stage after the show, after they’d cleaned up all of the underwear and everything. There was one old janitor, night watchman, and he said, “Very good show. Not a dry seat in the house.”

MAYBE IT HAPPENED to Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley. I don’t think it had ever reached the extremes it got to around the Beatles and the Stones’ time, at least in England. By the late ’50s, teenagers were a targeted new market, an advertising windup. “Teenager” comes from advertising; it’s quite coldblooded. Calling them teenagers created a whole thing amongst teenagers themselves, a self-consciousness. It created a market not just for clothes and cosmetics, but also for music and literature and everything else; it put that age group in a separate bag. And there was an explosion, a big hatch of pubescents around that time. Beatlemania and Stone mania. These were chicks that were just dying for something else. Four or five skinny blokes provided the outlet, but they would have found it somewhere else. It was like somebody had pulled a plug somewhere. The ’50s chicks being brought up all very jolly hockey sticks, and then somewhere there seemed to be a moment when they just decided they wanted to let themselves go. The opportunity arose for them to do that, and who’s going to stop them? It was all dripping with sexual lust, though they didn’t know what to do about it. But suddenly you’re on the end of it. It’s a frenzy. Once it’s let out, it’s an incredible force. You stood as much chance in a f---ing river full of piranhas. They were beyond what they wanted to be. They’d lost themselves. These chicks were coming out there, bleeding, clothes torn off, pissed panties, and you took that for granted every night. That was the gig. It could have been anybody, quite honestly. They didn’t give a s--t that I was trying to be a blues player.

For a guy like Bill Perks [bassist Bill Wyman], when suddenly it is in front of you, it’s unbelievable. We caught him in the coal pike with a chick, somewhere in Sheffield or Nottingham. They looked like something out of Oliver Twist. “Bill, we’ve got to go.” What are you going to do at that age when most of the teenage population of everywhere has decided you’re it? The incoming was incredible. Six months ago I couldn’t get laid; the next minute they’re sniffing around. And you’re going wow, when I changed from Old Spice to Habit Rouge, things definitely got better. So what is it they want? Fame? The money? And of course when you’ve not had much chance with beautiful women, you start to get suspicious.

I’ve been saved by chicks more times than by guys. Sometimes just that little hug and kiss and nothing else happens. Just keep me warm for the night, just hold on to each other when times are hard, times are rough. And I’d say, “F---, why are you bothering with me when you know I’m an a------ and I’ll be gone tomorrow?” “I don’t know. I guess you’re worth it.” “Well, I’m not going to argue.” The first time I encountered that was with these little English chicks up in the north, on that first tour. You end up, after the show, at a pub or the bar of the hotel, and suddenly you’re in the room with some very sweet chick who’s going to Sheffield University and studying sociology who decides to be really nice to you. “I thought you were a smart chick. I’m a guitar player. I’m just going through town.” “Yeah, but I like you.” Liking is sometimes better than loving.

Excerpted from the book Life by Keith Richards. ©2010 by Mindless Records LLC. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Co.

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

Why quitting your job is so difficult in Japan

Why quitting your job is so difficult in JapanUnder the Radar Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change