France's Islamic future?

Michel Houellebecq, the novelist who has found himself at the center of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, envisions the Islamization of France in his new book

On Wednesday, armed men, apparently Islamist terrorists, slaughtered a dozen editors and cartoonists in the Paris offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. It was the nightmare of secular liberals throughout the West, but especially in France, where anxiety about Muslim immigrants has been rising steadily in recent years, producing an ominous spike in support for the far-right Front National in last year's EU parliamentary elections.

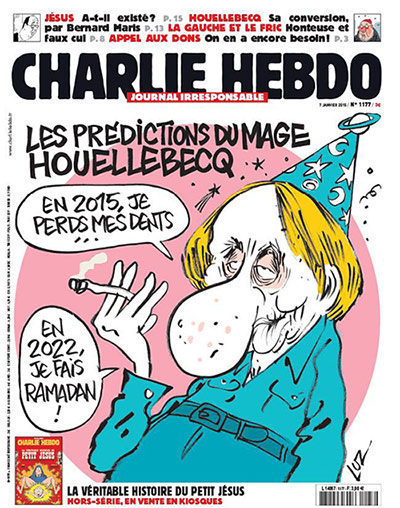

In an uncanny twist, a new novel by the controversial and award-winning French author Michel Houellebecq was published the very next day (a caricature of Houellebecq himself was splashed on this week's cover of Charlie Hebdo).

Titled Soumission (Submission), the book envisions a France seven years from now in which Marine Le Pen of the FN is pitted in a general election against the leader of a new Muslim party who goes on to win the presidency. The Islamization of French politics and culture soon follows.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If the events of Wednesday were a night mare scenario come true, the book published Thursday envisions its apotheosis — a fever dream from which secular France never wakes up.

A plot summary can make the book sound like the latest xenophobic screed of France's ascendant far right — a political tract designed to deepen paranoia and hysteria among those already inclined to fear North African immigrants. But if an extended interview with the author recently published in The Paris Review is to be believed (the book is not yet available in the U.S.), the truth is more complicated — and more worthy of sustained attention, especially by Americans looking to expand their ideological horizons and push themselves to understand the emerging shape of the 21st century in fresh ways.

To a remarkable extent, American political and cultural thinking takes place within well-worn, familiar grooves. The right is religious; the left is secular. The right frets about sexual liberation; the left cheers it. The right valorizes markets; the left views them with suspicion. The right praises individualism; the left longs for solidarity. The right defends nations and borders; the left longs for universalism. The right worries about the collapse of authority and the rise or moral and cultural decadence; the left does not.

In a series of earlier novels and essays, as well as in the Paris Review interview, Houellebecq has showed that he descends intellectually from a tradition of French culture that thoroughly scrambles these seemingly settled categories. Like Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Swiss by birth), Auguste Comte, and Emil Cioran (Romanian by birth) before him, Houellebecq personally rejects religion in all of its available institutional forms, while at the same time feeling personally drawn to it and believing (as he puts it in the interview) that society cannot "survive without religion" and that "religion, of some kind, is necessary." Indeed, Houellebecq suspects that France may be on the cusp of a resurgence of faith: "I think there is a real need for God and that the return of religion is not a slogan but a reality."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Such statements make Houellebecq sound like a relatively straightforward French analogue to the millions of Americans who make up the religious right. So do his highly critical views of feminism — at least until we delve below the surface of his occasionally outrageous pronouncements on the subject.

Feminism, for Houellebecq, is an outgrowth and extension of the atomistic individualism and neoliberal economics that have transformed social and cultural life throughout the Western world since the late 1960s. Market relations have penetrated every facet of life, including sexual intimacy. Thanks to contraception and widely available abortion, women and men are truly free for the first time in history to enjoy sexual pleasure without consequences. But in the process both have also found themselves consigned to an endless competitive scramble for a string of erotic "partners." Diets, workouts, constantly churning fashion trends, enhancement surgery, and the rising ride of anxieties that grow out of and inspire these and other manifestations of cut-throat sexual competition — the miseries of hedonistic capitalism multiply with each passing year.

Comte, one of Houellebecq's heroes, looked for salvation from the miseries of his own time (the mid-19th century) in the advent of a new "religion of humanity" that would succeed Christianity and the "abstract" character of modernity. But Houellebecq sees in all such human-centered proposals just another "philosophy handed down by the Enlightenment, which no longer makes sense to anyone." The religion we need cannot be a religion of humanity. It must be a religion of submission to something higher or greater than mankind.

Why not a return to Catholicism in France? Houellebecq is open to that possibility. Compared to philosophies derived from the Enlightenment, "Catholicism…is doing rather well." Yet Islam — the very name means submission of the will to God — intrigues him more, in part because the Catholic Church appears to have "already run its course, it seems to belong to the past, it has defeated itself. Islam is an image of the future."

That is what makes the plot of Submission so chilling. Far from blaming the rise of Islam in France on the immigration of foreigners who impose it on their host society through terrorism or post-colonial guilt-mongering, Houellebecq paints a picture of a near future in which formerly secular men and women deliberately choose to embrace Islam. Conversion becomes a prerequisite for schoolteachers. Women give up their careers (producing a drop in male unemployment) and adopt more modest dress. Polygamy is approved and practiced. With piety on the rise and stiffer criminal punishments on books, crime rates drop precipitously.

Christian (and post-Christian) civilization dies in France — and a new, more vibrant French-Islamic civilization is born to take its place. That is the arc of the novel's plot.

"What makes the book sad is a sort of ambiance of resignation," Houellebecq declares toward the end of the interview — resignation about having to say "goodbye to a civilization, however ancient."

This isn't how most of the French — or most Europeans — view their future, however anxious they may be about immigration from Muslim regions of the world. And it's certainly not what Americans, with their far greater enthusiasm for both Christianity and capitalism, see coming down the pike.

But perhaps for that very reason, Houellebecq's provocative premonition deserves to be pondered seriously by thoughtful readers on both sides of the Atlantic. No one challenges our dogmas or diagnoses the sources of our discontent in quite the same way.

Most of us will end up firmly convinced that he's wrong. But there's much we can learn by considering the possibility that he's right.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The 8 best spy movies of all time

The 8 best spy movies of all timethe week recommends Excellence in espionage didn’t begin — or end — with the Cold War

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

Are pesticides making florists sick?

Are pesticides making florists sick?Under the Radar Shop-bought bouquets hide a cocktail of chemicals