Bjork at MoMA: A review

In the midst of a career resurgence, the pop star gets a retrospective

The works of art that are most meaningful to us tend to be those with which we are most familiar. While Seurat's Port-en-Bessin, Entrance to the Harbor, for example, can overwhelm the passerby who pauses to admire its saturated whites and blues, it remains remote, a chilly artifact, haloed in the sanctity that comes from being one of the chosen few to grace the austere galleries of the Museum of Modern Art. It is very different from the less distinguished prints, paintings, and pottery that are fixtures in our homes, that we look at every day, abiding presences across successive apartments and eras that accumulate our affections the way a rock on the beach crusts over with barnacles. If we were to see our favorite vase in a museum, on a pedestal, under a spotlight, we would immediately feel alienated from it, as if it were no longer ours.

This familiarity extends to the books we have read so many times that their spines bend like hinges, or the albums that have grown old alongside us even as they evoke, with every listen, the people we once were. So it was with some trepidation that I went to MoMA on Tuesday morning to view a retrospective dedicated to Bjork, the 49-year-old Icelandic pop star who is enjoying a career resurgence thanks to the strength of her new album Vulnicura. The exhibit could prove to be the ultimate expression of a career that has spanned decades and disciplines, threading the years the way Bjork's work has stitched together music, video, haute couture, and fine art. It certainly would fuse the commercial and the highbrow, a defining characteristic for a woman who has sold millions of albums while keeping a foot firmly in the avant-garde. But by enshrining her work in the peculiar atmosphere of MoMA — one that vacillates between the clinical sterility of a mortuary and the herded frenzy of the security line at LaGuardia Airport — Bjork is running the risk of making her admirers feel, in some small way, that they have lost her.

Of course, Bjork's work is her own to give away, not ours. But to people of a certain generation, whose teens coincided with her rise to stardom, she will be forever linked to a time when we were beginning to discover art for ourselves, distinct from what was handed down to us by our parents or teachers. For most of us, this revelation came in the form of popular music, which was made by people just a little older than the older kids we already adored, and which spoke to us far more directly than literature or painting or movies. As Bjork sings on her second album Post: "My headphones/They saved my life," a sentiment that will be familiar to anyone who has ever been 13 years old, when the sonic landscapes between your ears often seemed far more real than those of the outside world. And the affinity for music at that age went well beyond mere identification with the artist, flourishing into an awkward kind of self-expression. We wore Nine Inch Nails t-shirts. Our bedrooms were festooned with posters of Kurt Cobain and D'Arcy. We made mixtapes that in their fastidious order and selection represented our own spin on the world. I remember a girl in the eighth grade openly carrying around the CD case for Debut as if it were an accoutrement, like a stud in her nose. The message she was sending was clear: This album — coy and brash, whimsical and funky, joyful and sad — is me.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

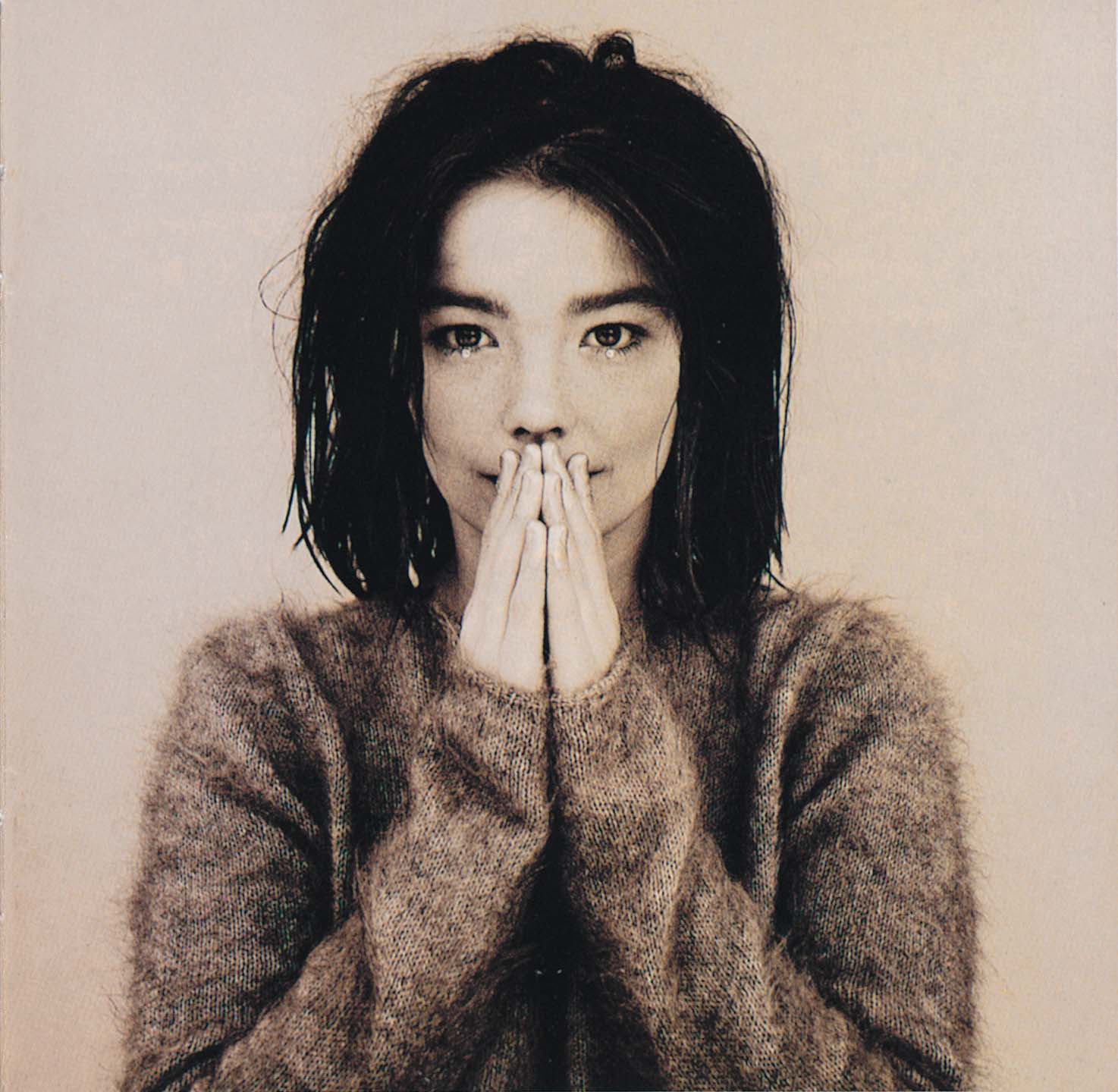

The ideal Bjork retrospective would somehow re-create that initial experience. We would relive the moment when we first laid eyes on the artist holding her steepled hands to her face in what seems to be a plea for kindness, her eyes dotted with two sequins that resemble tears poised to drop down her cheeks, an image that we only later discovered may in fact be an homage to Man Ray's Larmes. Or that moment, years later, when we first listened to Homogenic, ensconced in a cocoon of intimacy that was almost too near for comfort, suffused with emotions that we never would have copped to having outside the safety of our bedrooms.

This exercise in time regained is admittedly a lot to ask, so it is understandable that Bjork and MoMA, led by chief curator-at-large Klaus Biesenbach, have focused their energies on a less daunting project: marshaling the mind-blowing capabilities of audio technology to graft an entirely new experience to the familiar iconography of Bjork's work. But in so doing they have only hinted at the richness of Bjork's oeuvre, which fails to come to life here in any meaningful way.

The exhibit occupies three floors, with the lobby dominated by a custom-made gravity harp, used on the 2011 album Biophilia. It swings and plinks of its own volition like some industrial-strength version of the perpetual motion toy that sits on your boss's desk. The third floor is a series of interactive rooms called Songlines, each of which is dedicated to one of her eight solo albums. This idea of walking through music as if it were space, with different songs firing through your headphones as you move from room to room, is Bjork's answer to the question she posed herself before agreeing to go through with the exhibit: "How do you hang a song on the wall?" The music is overlaid by a fictional audio narrative written by the highly regarded Icelandic novelist Sjon, featuring a separate Bjorkian protagonist for each room.

Before you enter Songlines, a museum guide instructs you that each room should take about five minutes, and the entire tour about 40 minutes. But this is impossible, mostly because the rooms have barely anything in them. I was past the "room" for Debut, which amounts to a big screen projection of her video for "Big Time Sensuality" and a miniature doll of Bjork in her famous pose for the cover, in about 10 seconds, before realizing my mistake somewhere in Homogenic and backtracking to restart Sjon's narrative from the beginning. I shouldn't have bothered: incomprehensible if you try to tune into the music, pixie-ish to a maddening degree (I stopped listening when the character discovers "the power of the color pink"), the narrative is a study in everything that Bjork's detractors hate about her.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Once you succeed in ignoring the narrative, there just isn't enough in these cramped, snaking rooms to hold your interest for 40 minutes. The Bjork aficionado will be intrigued by the original Airmail Jacket that she wore for the cover of Post, designed by Hussein Chalayan, which is crinkled and satiny like an old envelope. The robots from Chris Cunningham's video for "All is Full of Love," each cast with Bjork's face, manage to echo the original's eerie melancholy. And Alexander McQueen's topless wedding dress for the "Pagan Poetry" video, a stringy mess of pearls, lace, and tulle, is the highlight of the installation, draped on a clear plastic mannequin of Bjork that spins slowly on a circular dias like the bawdy ghost of Miss Havisham. But as the mannequins amass, including one that inescapably features the notorious Swan Dress, the rooms start to feel perfunctory and just a little creepy, giving a new and unwelcome connotation to the song "Army of Me." Except in the most superficial sense, the rooms fail to convey the evolution of Bjork's work, as a good retrospective should do.

The main event, however, is on the second floor: a specially commissioned video for the song "Black Lake," from Vulnicura. It is a raw, anguished album that chronicles Bjork's separation from her longtime partner, the artist Matthew Barney. She has described it as a "total heartbreak" album, and "Black Lake," at 10 minutes long, is its centerpiece. The video is screened in a large, dark room that has been soundproofed with thousands of hand-stitched felt cones; it looks like the surface of an asteroid has been stripped and used as wallpaper. The music is wonderfully loud and buffets you from every direction, which is what I imagine it must be like to be trapped inside Kevin Shields' amplifier.

But for all these auditory fireworks, the star of the show is Bjork in some narrow cave. Her face, which in recent years has increasingly been obscured by all manner of masks and wigs, is refreshingly bare — distraught, pale, and regal, like some ice queen in exile. She thrashes her head from side to side. She beats her chest as if to jumpstart her dead heart. She pounds the volcanic rocks that surround her. It is a totally committed performance, reminiscent of the bloody, sweaty catharsis of punk rock. It is also 100 percent Bjork, except she is older, more desperate, and much sadder. The video ends on an uplifting note, with Bjork walking across a mossy field, but its emotional resonance comes from the dark recesses of that cave.

It's too bad, then, that the video installation isn't supported by a genuine monument to Bjork's career. In comparison, everything else seems hastily tacked together. Next door is another screening room, this one showing all of her music videos in a loop — that's it. In the age of YouTube, this part of the exhibit feels especially slapdash.

There are hints of what the exhibit could have been. As I was waiting to enter Songlines, I found myself in front of a video of Bjork performing a song from Vespertine, her album-length ode to her relationship with Barney. She is young, radiant, full of happiness — the perfect counterpoint to the bleakness of "Black Lake." It was, inadvertently, a poignant testament to the passage of time, to the way our lives can change so abruptly for the worse, and to the role music plays in preserving our past selves, reminding us that this, too, is Bjork, just as the 16-year-old who listened to her music is you. Then we were shepherded like cattle into those dreadful rooms.

There will be those who will frown on all this fuss, who will say that the Bjork exhibit is nothing but a tawdry gimmick to sell more tickets, who will claim that this is beneath a cultural institution like MoMA. Back when the exhibit was first announced, Jerry Saltz, the art critic for New York, said it was further evidence of MoMA's "suicidal slide into becoming a box-office-driven carnival," putting the Bjork show on par with crowd-pleasers like the Rain Room and Tilda Swinton in a box. He's not wrong: as anyone who has been to MoMA on a Saturday can attest, it has indeed become a zoo, a Disneyland for college-educated tourists wielding selfie sticks. But we should give Bjork a little more credit, not only because she is obviously a serious artist in her own right, but because, to paraphrase Karl Kraus, what is the Ninth Symphony compared to a pop song and a memory?

Bjork opens at MoMA on March 8.

Ryu Spaeth is deputy editor at TheWeek.com. Follow him on Twitter.

-

June 1 editorial cartoons

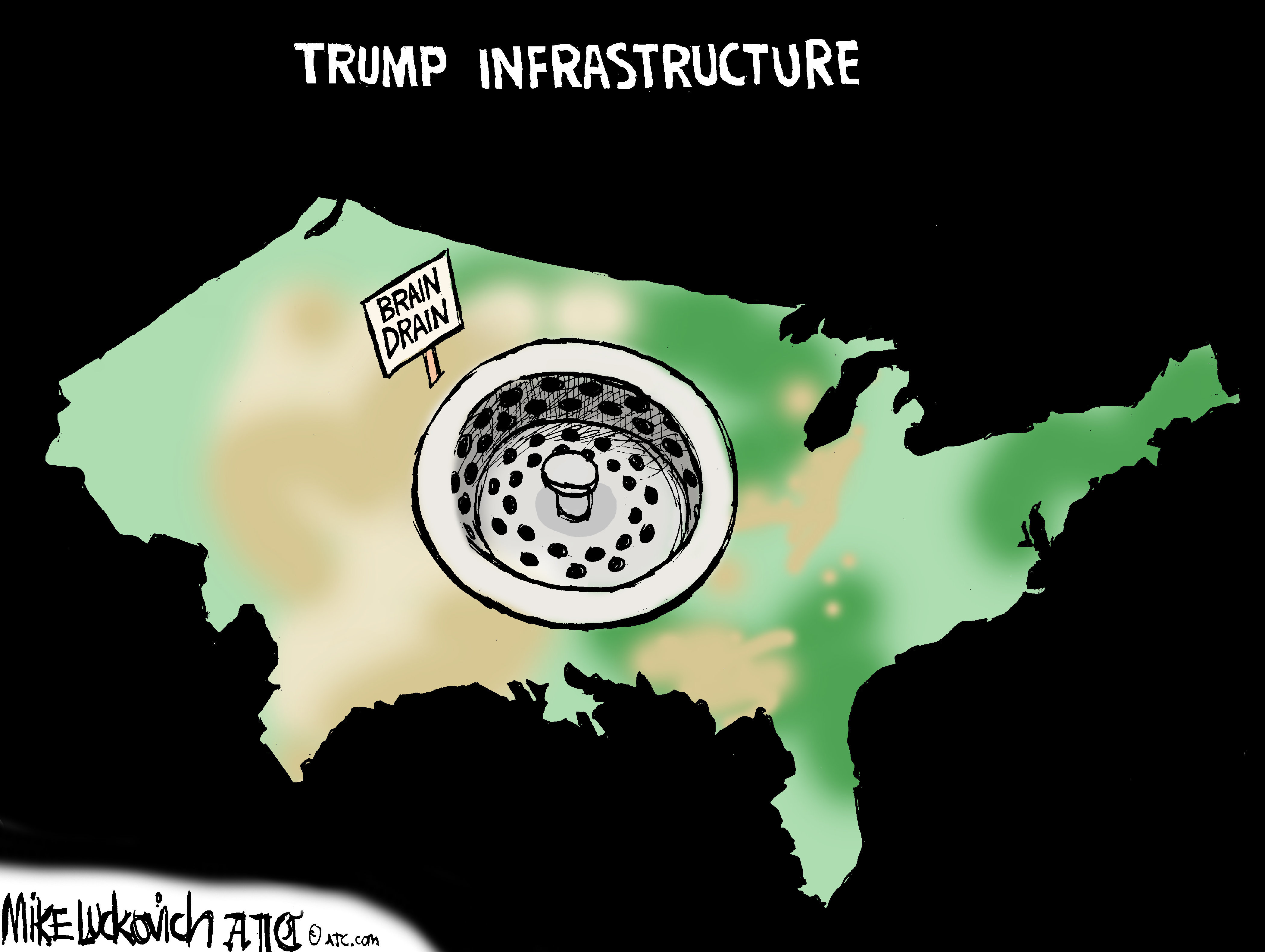

June 1 editorial cartoonsCartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Donald Trump's golden comb-over, brain drain in America, and a new TACO presidential seal.

-

5 cartoons about the TACO trade

5 cartoons about the TACO tradeCartoons Political cartoonists take on America's tariffs, Vladimir Putin waiting for taco Tuesday, and a new presidential seal

-

A city of culture in the high Andes

A city of culture in the high AndesThe Week Recommends Cuenca is a must-visit for those keen to see the 'real Ecuador'