Is America ready for the rise of the megaregion?

Part of our ongoing series on America in 2050...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1922, a small group of city planners and business leaders started studying New York City. It was the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties — a good time to be a New York resident, when Babe Ruth batted for the Yankees and F. Scott Fitzgerald debuted The Great Gatsby.

But the planning group also found that New York's influence — financially, socially, culturally — was not confined to its borders. Bridges linked the city to surrounding states, ports joined their coastlines, and thousands of residents passed between the city's financial heart and its outlying suburbs everyday. And as the region grew, the ties between the region only grew, too.

In 1929, the group released a report — aptly named "Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs" — that laid out a master plan for developing the interconnected communities of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. It was the first time planners had taken such a sweeping view of the area as a whole, living region.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Many of the ideas in the report stuck and the small group that produced it became the Regional Plan Association, a formalized group that still helps guide the area's planning today.

Decades later, the association's planners started looking outside of the New York region. They wanted to see if there were similar areas around the country that were just as tightly linked as the tri-state region.

New York, for example, was clearly part of the greater Northeast Corridor, which runs roughly from Boston to Washington, DC.

"It's very clear that we're part of a region that's even bigger than the tri-state region," said Juliette Michaelson, Vice President for Strategy at the Regional Plan Association. "There is a whole Northeast corridor that is clearly one interconnected region, economically, environmentally, in terms of ecosystems and transportation."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

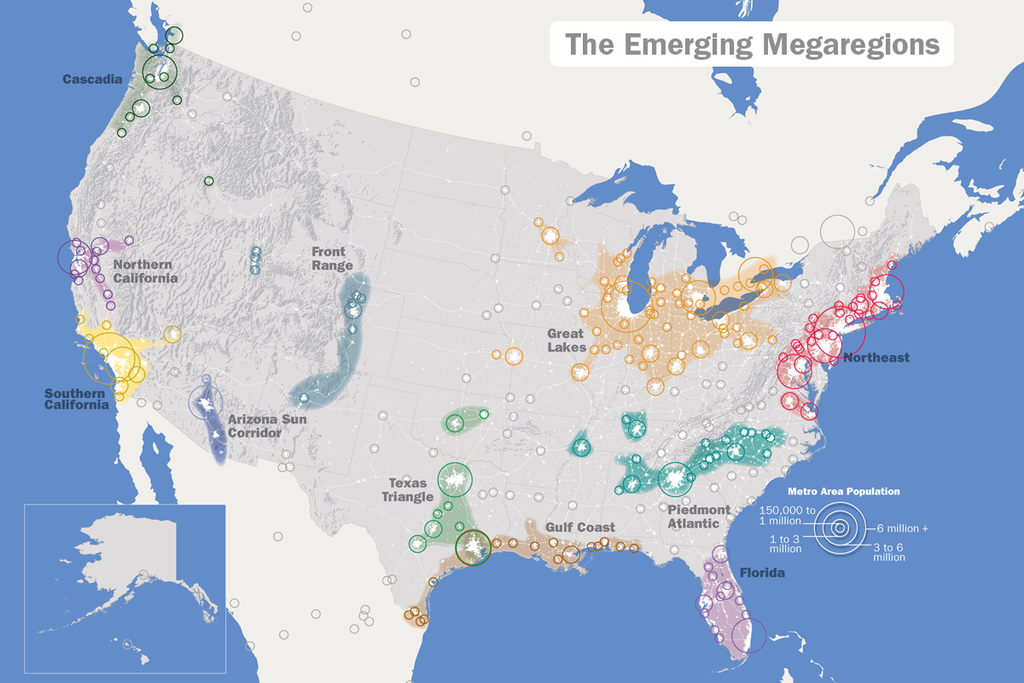

And there were other similarly connected areas around the country, they found. In 2011, they released a map — which ended up getting coverage everywhere from The Washington Post to Reddit — showing 11 total "megaregions" in the country. These big networks of cities, suburbs, small towns, and states could span anywhere from 100 to 600 miles, and were often linked by infrastructure like commuter rail lines or interstate highways.

Though the concept has existed in academia for decades, planners are now looking at these dense corridors of population, businesses, and transportation and wondering if the megaregion may, in fact, be the next step in America's evolution. With renewed interest and investment in urban centers and the projected growth of high speed rail, megaregions could easily become home to millions more Americans.

The Northeast corridor, for example, could receive up to 18 million more residents by 2050, according to estimates from the Regional Plan Association. And the region encompassing major cities in Texas including Houston and Dallas could see a spike from roughly 12 million to 18 million people in that same time, the association says.

And where population goes, economic growth is not far behind. The Northeast corridor would be the fifth largest economy in the world, with the Great Lakes megaregion at ninth and the Southern California megaregion outpacing Indonesia, Turkey, and the Netherlands as the 18th largest, according to 2012 estimates from real estate advisory RCLCO.

The problem is, there are challenges to making these networks hold together. Unlike megaregions in Europe and Asia, for example, the United States has traditionally shied away from large umbrella governing organizations which surpass state borders.

"In a lot of other world cities, not only do they think of themselves as part of megaregions, they also have government organizations at the megalevel," said Michaelson of the Regional Plan Association.

The United States, by contrast, has neglected "megalevel" planning organizations, with the possible exception of Amtrak, which operates rail service through many of the proposed megaregions but which struggles to maintain funding levels from the federal government.

Some scholars think the lack of regional planning will need to change. A 2013 Brookings Institution report by scholars Jennifer Bradley and Bruce Katz concluded that major metropolitan areas will be largely left alone to grow and develop their economies as "the U.S. government is mired in partisan division and rancour." With these areas generating 91 percent of the country's GDP, according to the report, metro regions will increasingly become "the engines of economic prosperity and social transformation in the US."

But on a purely practical level, cooperation between cities and states can still be rare today in these large regions that cross state lines, according to David Wachsmuth, a political economist at the University of British Columbia.

"When you start talking about coordinating policy across 10 cities and hundreds of miles, that's almost an impossible task," he said. "Cities have their autonomous power and there aren't a lot of incentives at the local level to cooperate with their neighbors."

That may be changing. Governor Dannel Malloy of Connecticut, for example, has been vocal about working with state governments throughout the Northeast to widen the congested I-95 corridor that snakes up the East Coast. Even the federal government has acknowledged the inevitability of megaregional planning as it lays out plans for high-speed rail and highway improvements.

And both Wachsmuth and Michaelson acknowledge that much of the hard work of building a megaregion isn't simply about adding faster trains or more durable bridges. Instead, much of it comes from creating a shared identity, something that can only happen organically.

"If you look at the Gulf Coast, there is already a Gulf Coast identity that crosses city and state lines," Wachsmuth said. "The Atlanta and Charlotte area in the Southeast may see a regional identity there, too. But most people in Boston probably think of themselves as Bostonians. They don't think of themselves as having much in common with someone in Maryland."

Michaelson sees this slowly changing. Even in drought-stricken California, which has traditionally been culturally divided between north and south, mutual concerns have begun to forge a shared regional identity.

"I can imagine people for the first time are aware of the fact that their water needs are connected to water resources elsewhere in their megaregion," she said.

And that's one of the keys to megaregional planning, she says.

"You need to think at a scale that's bigger than your individual community."

Matt Hansen has written and edited for a series of online magazines, newspapers, and major marketing campaigns. He is currently active in press freedom and safety research with Global Journalist Security.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military