Americans have never had more choices. And it's making us miserable.

In their personal lives, Americans have never been freer — from obligations, expectations, restrictions, constraints. Most of us consider this a hard-won achievement, a sign of progress beyond the limitations with which our parents, and their parents, and their parents' parents, had to contend.

But is it really progress? Are we happier in our boundless autonomy — or more miserable?

Those are the thoughts and questions that came to mind as I read Jordana Narin's sad, insightful, award-winning "Modern Love" essay in last weekend's Sunday Styles section of The New York Times. A Columbia University sophomore, Narin wrote about her years-long…something with a young man named Jeremy.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The two met at summer camp when she was 14. They saw each other next in 11th grade at a Halloween party. They flirted awkwardly, then kissed. Over the months and then years that followed, they got together periodically and hung out. Sometimes they'd fool around. Eventually they had sex.

At no point did they discuss what they were doing, or clearly express what they felt for each other. Refusing labels, relishing the freedom that comes from not defining an interaction that involves communication, attraction, and sex, the couple ended up floating in a no-man's-land that is somehow not friendship nor a love affair nor an act of courtship moving toward marriage. It certainly never developed into anything entailing obligation or exclusivity, which would feel too confining, oppressive. Better, apparently, is hovering above constraint, enjoying the occasional satisfaction of physical desire, and then drifting away to another coupling with another person, until the next time.

But of course, this isn't "better" at all. The pathos of Narin's essay comes from her knowing awareness of how unsettled, anxious, and lonely she feels about her non-relationship with Jeremy — together with her unwillingness to reject the assumptions that have led the couple into this state of interminable ambivalence in the first place.

What Narin describes is a variation on the ideal of freedom that Matthew Crawford explores and criticizes so masterfully in his new book, The World Beyond Your Head. It is freedom understood as the autonomy of the individual from all external constraint. Freedom — and the possibility of happiness or fulfillment — is achieved, in this view, when the individual breaks free from limitations to attain a state of pure potentiality, confronting a vista of endless, open possibilities.

Crawford focuses on the complicated ways that technology and corporate capitalism conspire to create virtual worlds that grant us the illusion of autonomy — a process that generates various cultural and psychological pathologies that multiply all around us every day. A parallel dynamic can be seen in the evolution of our interpersonal, and especially romantic and sexual, relationships over time — an evolution that serves as the backdrop to Narin's essay.

Marriage was once close to ubiquitous, and couplings were often arranged by families. When they weren't arranged, they nearly always took place within rigidly defined cultural, religious, and ethnic boundaries. By the age of 25, and usually long before, you were bound to another person, in most cases for life. Most people accepted these constraints, though they also created the conditions for tragic drama. When Romeo and Juliet fell in love in defiance of social conventions, the result was great suffering and death. Individuals might fight against received constraints, but in the end the constraints always won.

Or at least, they did for a long time. In more recent centuries and decades, we've seen a slow but dramatic shift in the direction of individual autonomy, accelerating to the present day. It began with the rise of the ideal of romantic love, which led to marriages based more and more often on free choice. Eventually the old cultural, religious, and ethnic boundaries broke down, making way for all sorts of once-unthinkable intermarriages.

And all sorts of once-unthinkable reasons to end a marriage. First there was an escape clause for abuse and abandonment, then a list of lifestyle considerations (including a couple "growing apart"). Eventually divorce could dissolve a supposedly indissoluble, ostensibly life-long bond for any reason at all, without attributing "fault" to either party.

Each step was a tiny triumph for autonomy; together they amounted to a cultural revolution that left the institution of marriage — and the thick web of norms and practices that directed young people toward it — profoundly transformed.

And yet, for all of these changes, the institution of marriage, plus at least some of those norms and practices, persisted as a cultural ideal.

Until now, that is. With the rise of the millennial generation, marriage itself — along with formal dating, exclusive dating ("going steady"), and engagement — has come to seem for many like an unwanted obstacle to personal autonomy. And it's easy to understand why.

You are never freer than before you make a decision: Do I opt for X and live with the consequences of having done so, including the consequences of having foreclosed the very different consequences that would have followed if I'd gone for Y instead? Or do I decide for Y and live with not having chosen X? To choose is to exclude a whole range of possible futures, to rule out countless opportunities.

The moment you choose, the world seems smaller, because now you're in a relationship, now you're engaged, now you've agreed to marry and spend your life (or at least a good long while) with this person and not some other person who might turn the corner 10 seconds from now and be more beautiful, more interesting, or just different than the person I just defined as "my boyfriend." How foolish it can seem — to choose, when the consequence of choosing is to limit oneself, to rule out (or make much more complicated) the possibility of having ever more and ever different experiences, ever more and ever different pleasures, with ever more and ever different people.

That's the reality Narin so painfully recounts in her essay. Why not tell Jeremy how she feels, her father asks? Because, she notes, "Jeremy and I are technically nothing."

Without labels to connect us, I have no justification for my feelings and he has no obligation to acknowledge them…. But by not calling someone, say, "my boyfriend,"… he becomes something else, something indefinable. And what we have together becomes intangible. And if it's intangible it can never end because officially there's nothing to end. And if it never ends, there's no real closure, no opportunity to move on. [The New York Times]

Life in suspended animation. That's what a life of perfect freedom, perfect autonomy, amounts to. In science fiction, suspended animation is a state of deep sleep, in which aging, like living, all but stops for a time, only to be resumed later. The person choosing not to choose, by contrast, goes right on living and, in effect, chooses by default to live in a particular way — in a way that suspends or defers the choices and decisions that make up a full life, and a possibly fulfilling life.

To live fully we must face the range of possibilities before us, make choices, and live with the consequences of those choices, even though it means resigning ourselves to limits, to something less than complete personal autonomy. The alternative is to live, to age, and to die without ever truly defining ourselves, without ever transforming our potential, our possibilities, into something real, something actual, something lasting, and worthwhile, and substantial — something, in a word, that just might resemble happiness.

No wonder Jordana Narin sounds so very sad in her nearly perfect freedom.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Today's political cartoons - March 30, 2025

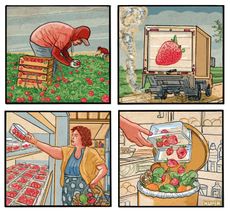

Today's political cartoons - March 30, 2025Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - strawberry fields forever, secret files, and more

By The Week US Published

-

5 hilariously sparse cartoons about further DOGE cuts

5 hilariously sparse cartoons about further DOGE cutsCartoons Artists take on free audits, report cards, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Following the Tea Horse Road in China

Following the Tea Horse Road in ChinaThe Week Recommends This network of roads and trails served as vital trading routes

By The Week UK Published