The ghosts behind Seymour Hersh's phantom conspiracy

How did the legendary journalist get duped into writing a completely implausible account of the Osama bin Laden killing?

In 1983, investigative journalist Seymour Hersh published a book about Henry Kissinger that included a sensational story about Richard Nixon, nuclear brinksmanship, and Vietnam.

Based on sources both anonymous and named, Hersh contended that in 1969, Nixon decided to convince the North Vietnamese that he was a lunatic. The president's method: to pretend to use the American nuclear arsenal under his command as if he were irrational. Over the course of three weeks in October that year, the Joint Chiefs of Staff put American strategic forces on heightened alert, ordered random dispersals of airborne emergency command posts and refueling planes, and tasked the Air Force with provocative sorties that took them near the Soviet Union. The situation between the U.S.S.R and the U.S. was not particularly tense at the time; there was no reason for these alerts. And they went way beyond normal military exercises.

When Hersh first published his story, it was met with incredulity. Not only was it unthinkable that a president, even one with Nixon's brain, could do such a thing, but the very idea that he could push such a risky idea through the military bureaucracy was seen as absurd.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Hersh, it turns out, was mostly right. He got a few details wrong — the military never went to DEFCON 1, for example, but his implausible account of a madman with his finger on the trigger really did happen. Nixon's chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, later quoted the president thusly: "I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe that I've reached the point that I might do anything to stop the war. We ́ll just slip the word to them that 'for God's sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about Communism. We can't restrain him when he is angry — and he has his hand on the nuclear button."

The manufactured war alert was the manifestation of that dreadful policy.

When I first read Hersh's account of the killing of Osama bin Laden, I thought immediately of the skepticism that greeted his 1983 blockbuster.

And I wondered: How could a guy who managed to uncover truly awful things manage to hoodwink himself so thoroughly today?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

With his wrinkled suits, messy hair, and pinched face, Hersh could be mistaken for an assistant professor at a middling university who never quite managed to join the tenure track. He is, in real life, one of the best journalists who ever lived, because the scandals he exposed set history straight (what really happened to Korean Air Lines Flight 007), changed policies (My Lai), and held powerful interests accountable (Abu Ghraib). He has seen wrongdoing up close. He knows how it smells.

And something apparently smelled rotten to him in Abbottabad circa 2011. "Would bin Laden, target of a massive international manhunt, really decide that a resort town 40 miles from Islamabad would be the safest place to live and command al Qaeda's operations?" he asked. Apparently not. Instead of Zero Dark Thirty, the truth, he says, is that the military, intelligence services, and political leaders of the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia brokered a secret deal to cover up a conspiracy to assassinate Osama bin Laden, who had been trapped for years in a Saudi-funded prison by the Pakistani intelligence service.

How is that really, really smart people can come to believe really, really stupid things?

Is there some tick that Hersh, whose instinctive skepticism about American foreign policy borders on the Chomskian, developed over time? Has he lost his edge, because of age, or because of the passage of time and the passing away of sources? Does the quintessential independent journalist feel too far removed from the center of this epoch of journalism, with its Snowden-centric secrecy porn? I don't know nearly enough to look inside the man's head. No one does.

When Hersh has reported on policy gone wrong — i.e. bad policies often abetted by casual lies — he's been an ace. At his best, he tears apart the judgments that lead to catastrophes.

When he has ventured in the realm of motive, he is much less reliable. His book on the Kennedy mystique was replete with, to be generous, glittering generalities and dot-connecting where dots shouldn't have been connected. Camelot was, of course, a myth; the major truth was right and already well-known, but there was too much flotsam in service to it. His assertions about the U.S. military and secret societies have been disproven and their relevance, even if true, are unclear. His stories on Syria and chemical weapons use, which relied largely on his interpretation of the motives of political factions and leaders in the region, have not stood up to scrutiny. His revisionist tale of Osama bin Laden's killing hinges on a grand conspiracy about motive. It is not even plausibly implausible.

Events of powerful impact must have powerful causes, or else we feel helpless. I don't think Hersh is paranoid or politically dispossessed. He's a fairly wealthy guy who is capable of getting attention whenever he wants it, and isn't in danger of being killed. But Hersh has been lied to all of his professional life by people in power; he's a journalist who has seen his reporting about true events, like prisoner abuse, trashed by officials who knew he was right; a man who never accepted the keys to the kingdom because he did not want to compromise his independence; a person whose life experience has taught him that if something is wrong, it must also be bad. And usually, someone, somewhere, has done something dastardly.

Unfortunately (or fortunately), not every politician thinks like Richard Nixon or Henry Kissinger.

Did 22 fairly ordinary men really hijack airplanes and topple the World Trade Center and destroy a quarter of the Pentagon on 9/11? Yes. Did a gaunt loner, angry at his government's treatment of Cuba, chance upon a job that gave him a sniper's perch over John F. Kennedy's motorcade route in 1963? Yes. Did the United States go to war with Iraq because its leaders believed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, ignoring not out of malice but because of judgment the evidence to the contrary? Yes. Did Bashar al-Assad's troops use chemical weapons against Syrian rebels? Yes.

The effects of these — 9/11; the assassination of a president; the horrors of war — far outweigh the banal sequence of events that caused them. So does the killing of Osama bin Laden.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

‘The economics of WhatsApp have been mysterious for years’

‘The economics of WhatsApp have been mysterious for years’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

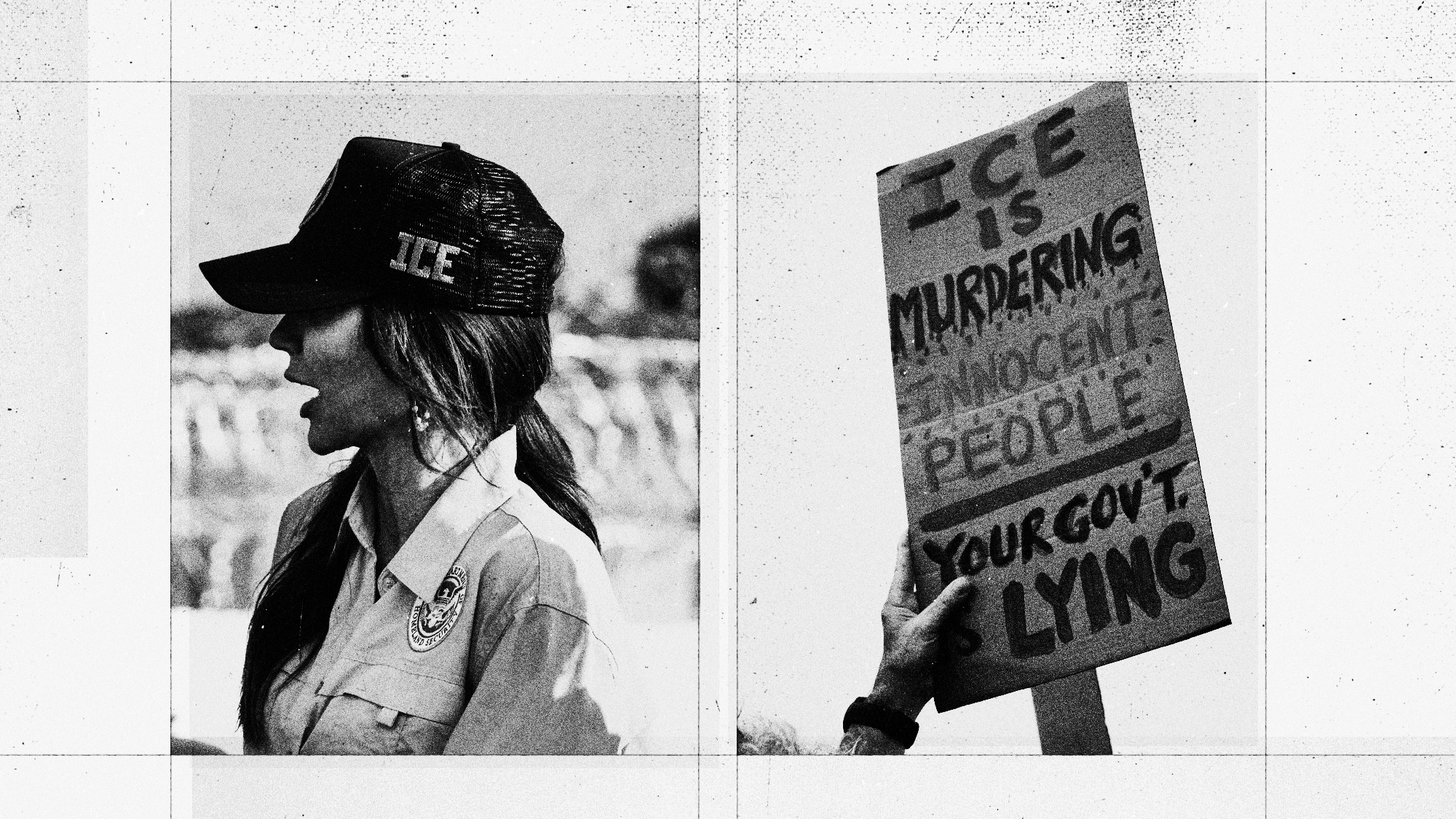

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?Today’s Big Question Centrists, lefty activists also debate abolishing ICE

-

Is a social media ban for teens the answer?

Is a social media ban for teens the answer?Talking Point Australia is leading the charge in banning social media for people under 16 — but there is lingering doubt as to the efficacy of such laws

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

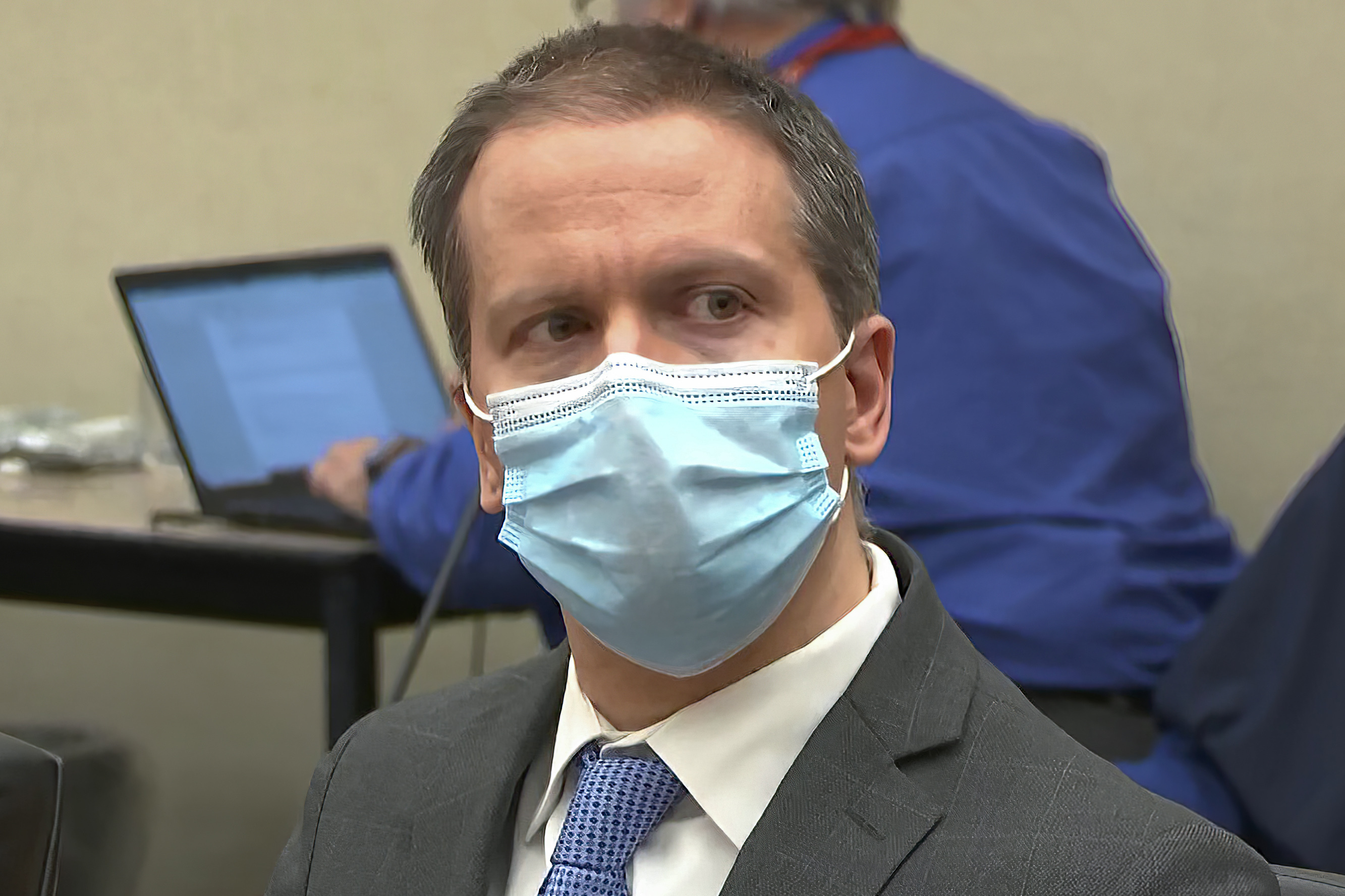

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read