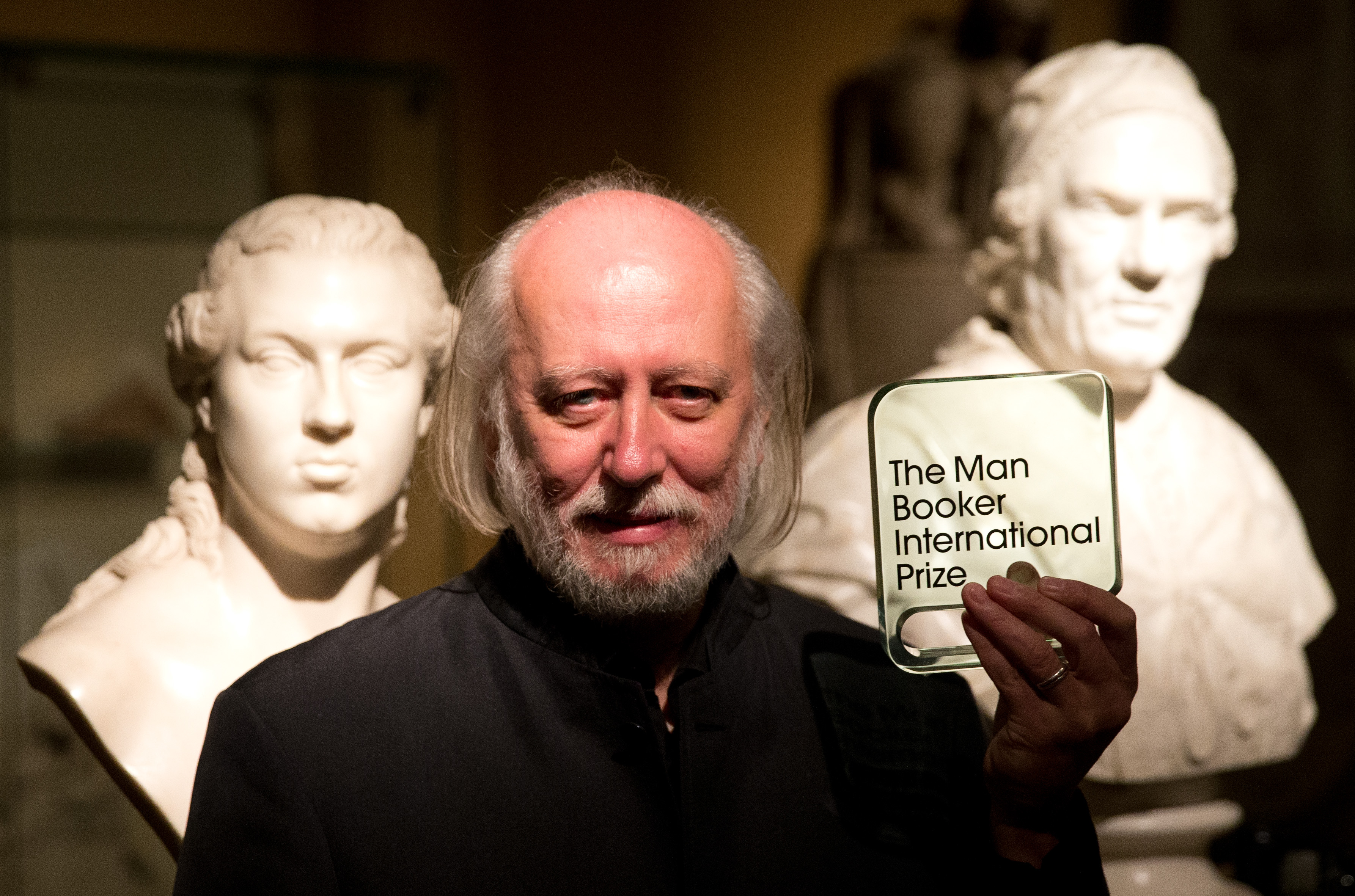

Is Laszlo Krasznahorkai about to be huge?

The winner of the Man Booker International Prize takes a rare turn in the spotlight

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Earlier this year, The New Yorker ran an essay called "Knausgaard or Ferrante?", a blunt choice that captures how these two European authors have come to dominate discussions of contemporary fiction in America. To this formulation it is tempting to parenthetically add, as if under one's breath, "or Krasznahorkai."

The Hungarian novelist has in recent years garnered similar adulation from Anglophone critics, but has yet to break into mainstream consciousness to the same degree. Ferrante is an international woman of mystery, Knausgaard is almost literally a rock star, but Laszlo Krasznahorkai remains something of a well-kept secret. "His work," James Wood once wrote, "tends to get passed around like rare currency."

That might change starting this week, now that Krasznahorkai has been awarded the Man Booker International Prize. Bestowed every two years for a body of work in English or translated into English, the prize aspires to be a kind of alternative to the Nobel Prize for Literature. The previous winners read like a list of longtime Nobel contenders — Philip Roth, Chinua Achebe, Ismail Kadare — and include one actual Nobel winner in Alice Munro. Krasznahorkai, in other words, has just joined a very exclusive club, one that glows with so much prestige that his books should become more attractive to readers, publishers, and booksellers.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At the same time, it's easy to imagine Krasznahorkai remaining rare coin. Unlike Knausgaard and Ferrante, whose books are instantly accessible, his work is difficult, a dreaded designation in an age of instant gratification. His sentences can be long, pages and pages long. They can be as dense as sludge. They don't proceed with the directness of an arrow's flight, but meander and loop upon themselves, flowing like some turbid river, thick with humanity's flotsam, that never quite escapes to sea.

He is a writer whose vision is total, of which each book seems to represent only a segment. Together they constitute a contained fictional universe that is like a skewed version of our own. The books are grounded in reality — "reality examined to the point of madness" in his phrase — but there are fantastical elements, too: biblical rains, a girl resurrected from the dead and flown through the air like a magic carpet. As Ottilie Mulzet, one of Krasznahorkai's translators, explained in an interview with Quarterly Conversation, this is a universe with a peculiar logic of its own, almost a theology, replete with archetypal figures who recur in every book: the Prophet, the Seeker, the Archivist. To enter this universe for the first time is to feel a little lost, as if one could use a tour guide, or perhaps an anthropologist, to explain its history and people.

Still, Krasznahorkai offers many pleasures to the casual reader. Those long sentences are not a slog, but a trip. Take this comparatively short one from Satantango, his first novel, originally published in 1985, but only released in the U.S. in English in 2012. Satantango, more or less, is about the dissolution of a poor collective farm in Hungary, the kind that was common under the communist leader Janos Kadar. This passage gives a sense of Krasznahorkai's obsession with civilizational decay, as well as his penchant for connecting our mortal ruin to the cosmic:

Irimias scrapes the mud off his lead-heavy shoes, clears his throat, cautiously opens the door, and the rain begins again, while to the east, swift as memory, the sky brightens, scarlet and pale blue and leans against the undulating horizon, to be followed by the sun, like a beggar daily panting up to his spot on the temple steps, full of heartbreak and misery, ready to establish the world of shadows, to separate the trees one from the other, to raise, out of the freezing, confusing homogeneity of night in which they seem to have been trapped like flies in a web, a clearly defined earth and sky with distinct animals and men, the darkness still in flight at the edge of things, somewhere on the far side of the western horizon, where its countless terrors vanish one by one like a desperate, confused, defeated army. [Satantango]

As Paul Kerschen explains in an excellent overview of Krasznahorkai's work in the journal Music & Literature, Satantango is part of what could be considered the writer's Hungarian novels. These books, with their allegorical references to life under European communism in the post-war era, were the first to be translated into English. They were what made Krasznahorkai intriguing to American critics like Susan Sontag, who famously proclaimed him, with typical cover copy flair, "the Hungarian master of the apocalypse." If Kafka foretold existence under totalitarianism, then writers like Krasznahorkai and Albania's Ismail Kadare could testify that its absurd horrors were real. In this respect, Krasznahorkai and his ilk serve both a historical and literary purpose. As Joshua Cohen once wrote of Sontag's effusive praise of another Hungarian master, Peter Nadas, the enthusiasm for Eastern European writers partly stems from "an irrational desire to find the embers of Modernism still burning behind the Iron Curtain."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But it would be a mistake to reduce Krasznahorkai to a pendant on the Kafka family tree, for the Hungarian novels are only half the story. Krasznahorkai has also written a series of Asian novels set in China and Japan, only one of which, Seiobo There Below, has been translated into English. (More are coming.) And here we see his concern with civilization's collapse broaden beyond the catastrophe of 20th-century communism, to encompass a world that has exchanged its connection to the sacred for the complacent comforts that come from being part of a new global bourgeoisie.

Seiobo There Below is a collection of linked vignettes that each focus on a vessel for the sacred, all of which take the form of ancient or timeless works of art. As Mulzet puts it, Seiobo is "an exquisitely rendered 'wunderkammer' of the treasures of our human civilization," animated by "the burning question of how we are able to receive them into our consciousness — these artifacts, with their overwhelming, impossible burden of conveying the sacred to us in everyday life."

So Seiobo skips, across time and space, to Alhambra, the Parthenon, and the Renaissance, where the characters catch fleeting glimpses of the divine. They do not emerge from these experiences bathed in the mellow light of heaven: they are disoriented, blinded, terrified. Whether Westerners are still capable of even accepting this gift is called into question, and Krasznahorkai's view of the matter shares similarities with Rilke's famous line about why we worship the angel's beauty, "because it serenely disdains to destroy us." Angels, heaven, the sacred — they are so alien, so completely cut off from our lives, so perfect while we are flawed, that we can only respond to their presence by sinking into a confused melancholy.

A different dynamic is at work in the stories set in Japan, where the sacred is revealed, and tempered, by a painstaking craftsmanship. Krasznahorkai's writing has a natural affinity for the Japanese obsession with detail, which comes through in gorgeous passages describing in granular particulars the restoration of a statue of Buddha, the carving of a Noh mask, and the ritual rebuilding of the Ise Shrine, parts of which are identically reconstructed — from scratch, from memory — every 20 years. By maintaining those traditions, by bowing before a very strict set of rules and customs, the sacred magically emerges from plain materials. The sacred inhabits the statue, the mask, the shrine, the thing itself — indeed, is the thing itself.

…the statue presumably dates from the beginning of the Kamakura era, and one could enumerate where the diadems are individually placed on the head, where they can also be accordingly individually removed from the head, as well as both the ears and the chest, all of that; and the harmonious body sits in the lotus position, covered by folds of fabric, carved with miraculous sensitivity, although of course the most precious thing of all in the statue are the eyes, and this is also what makes it so celebrated in the opinion of experts — the half-lowered eyelids or, put another way, the only half-opened eyes, miraculous, astounding; they give the statue and every Amida statue, as its essence, the infinite suggestion of one immortal gaze, the influence of which one cannot avoid; it is a question all in all, of that one single gaze; so that the sculptor, sometime around the year 1367, wished to depict, to capture with his own unfathomable genius of artistic technique that one single gaze, and this depiction and this capturing, even in the most restrained sense of the word, was successful… [Seiobo There Below]

As Mulzet points out, unlike Satantango, where the very sentences seem to slosh in mud, the writing in the Asian novels is sharp and clean, as if surrounded by the white space of a calligraphic scroll.

This is not to say that Krasznahorkai finds some kind of trite salvation in Asian spirituality. As Kerschen writes, the Asian novels contain an ambiguous message: "Art is the solace we have while our days last, and that is all. Or else it is the veil behind which the gods move." In this search for solace, Krasznahorkai is a pilgrim, or to borrow a figure from his elaborate schema, a Seeker; he is also an Archivist and perhaps a Prophet, one to whom a certain devoted throng will surely flock.

Whether more will join them remains to be seen. But with more of his Asian novels appearing in translation, and more accolades to come, it may be that his journey has just begun.

Ryu Spaeth is deputy editor at TheWeek.com. Follow him on Twitter.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix