How CBS's The Briefcase continues a long American tradition of putting the poor under a microscope

The Briefcase examines the ethical agonies of those struggling to make it. But what about the wealthy?

Have you heard of The Briefcase? The reality TV show debuted last week on CBS, and was the most watched of the three premieres that night. I wasn't among the viewers, but a number of other writers were. And man, it's gotten them talking.

The premise is deviously surgical: A family "experiencing financial setbacks" is given a briefcase with $101,000. That first $1,000 is for them to spend as they'd like, to get a taste of life without constant anxiety about the checkbook. Then comes the twist: The family is presented with an anonymous second family, in economic straits as bad or worse. Family number one then has to decide how much, if any, of the $100,000 to share. They actually go through several iterations of the decision-making process, with increasingly more information provided about the second family's bills, debts, and struggles.

If Margaret Lyons' summation at Vulture is any indication, the result is pretty gut-wrenching:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the two episodes CBS made available for review, the decision weighs incredibly heavily on all participants. One woman is so overcome that she vomits. Everyone talks about health insurance. Several people claim this is the hardest decision they've ever made. Many, many tears are shed. And perhaps unsurprisingly, people demonstrate impressive generosity. [Vulture]

The final zinger is that, at the episode's conclusion, it’s revealed that both families were given a briefcase, and put through mirroring rigamaroles regarding the other.

There are a lot of directions from which to attack this: the way the premise mucks with class awareness to render the truly impoverished invisible; the relentless and unseemly exposure of deeply intimate struggles; the way things swing perilously close to exacting assessments of whether everyone's lifestyle is sufficiently disciplined and responsible. But by all accounts, the show is not so much judgmental as it is simply crass.

As far as I can tell, what's interesting is what The Briefcase doesn't show: any broader political context for why these families face the situations they do. Unemployment, inequality, financial insecurity — if these things are not evidence of personal moral failure, then they are presented as things that just "happen," like the weather. The only thing to be done is endure, and get a tad philosophical. "Like its predecessors," Mary Elizabeth Williams wrote at Salon, "The Briefcase pretends to impart the lesson, uttered by one of the contestants in the final moments of the first episode, that 'Money's not everything.'"

That's a fine sentiment, but by all accounts The Briefcase does a great job of showing how money can come pretty damn close to being everything. There's the aforementioned tears and vomiting and agonizing over health care. But there's also marital strife as spouses disagree over how to allocate the funds, which leads them to shame one another into "doing the right thing."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's also the weird way widespread economic insecurity can inspire a kind of survivor's guilt. After watching the show, Chelsea Kiene of the Center for American Progress was reminded of her own family’s hardships back in 2006:

I prayed that another plant would be closed instead of my father's... In hindsight, I was, in effect, making the same judgment call that families in The Briefcase are asked to make: to determine whether the very real struggles and economic hardships of their own family supersede the dire financial circumstances of another family. [TalkPoverty]

This reveals the "money isn’t everything" talk for the asinine mysticism it is. The grief and agony and the incipient civil war these families are going through is obviously a result of scarcity. Take the scarcity away and you take away the structural cause of their suffering. And that gets at the ultimate political purpose that the money-isn't-everything mysticism serves: If we acknowledge that scarcity is the issue here, that leads directly to asking where the scarcity comes from, and how it might be alleviated.

As Lyons bitterly notes, Les Moonves, the president of CBS, made $54 million in 2014. The $101,000 in the briefcase is 0.2 percent of that. "Is Les Moonves pulling his car over to throw up because he's so paralyzed by trying to do the right thing?" Lyons asked. "If he is, make a show about that. If he's not, make a show about why not."

But we could get way more fun than that. Would Moonves be cool with the government taxing 90 percent of every dollar he earns over $300,000 a year, and using that to fund a bulked-up safety net to help families like those on The Briefcase? How about we alter the inflation target in monetary policy, so that the value of the financial securities Moonves has bought deteriorate in value faster, but the economy also provides more jobs those families could get? What about squashing free trade deals if they don’t include laws on currency manipulation? Or having the federal government reform labor law to empower unions, so the families that work for CBS could score higher wages, albeit at the cost of the remaining revenue that can go to Moonves and shareholder payouts?

Politicians, bureaucrats, journalists, economists, analysts, think tank presidents, and CBS media moguls all hail overwhelmingly from the country's upper class and wealthy elite. To a far greater degree than anyone else, they spend their time determining what policies should govern the workings of the economy as a whole. That's a big part of the daily lives they lead in our society, and its the shape of their interactions with the rest of their fellow human beings.

So we could ask them all those same questions. We could make a TV show about that. Not exactly sexy questions, but they matter enormously for how and when and whether money and resources flow to the families The Briefcase highlights.

Does supporting cuts to food stamps and Medicaid say as much about your character as what these families do with the $100,000 says about theirs? You'd think so, but such a suggestion remains uncouth and uncivil as far as U.S. politics is concerned. Divorce, debt, employment, abortion, sex, parenting — these are questions of morality. Whether the macro design of our economy leads to mass hardship and anxiety and grief? That's merely a technocratic matter, over which well-meaning (and crazy well-off) people on all sides of the political divide should be able to amicably disagree.

The Briefcase continues America's well-worn tradition of keeping the microscope on the messy, intimate, painfully human decisions of less fortunate Americans. Which conveniently means the microscope isn't investigating anyone else.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

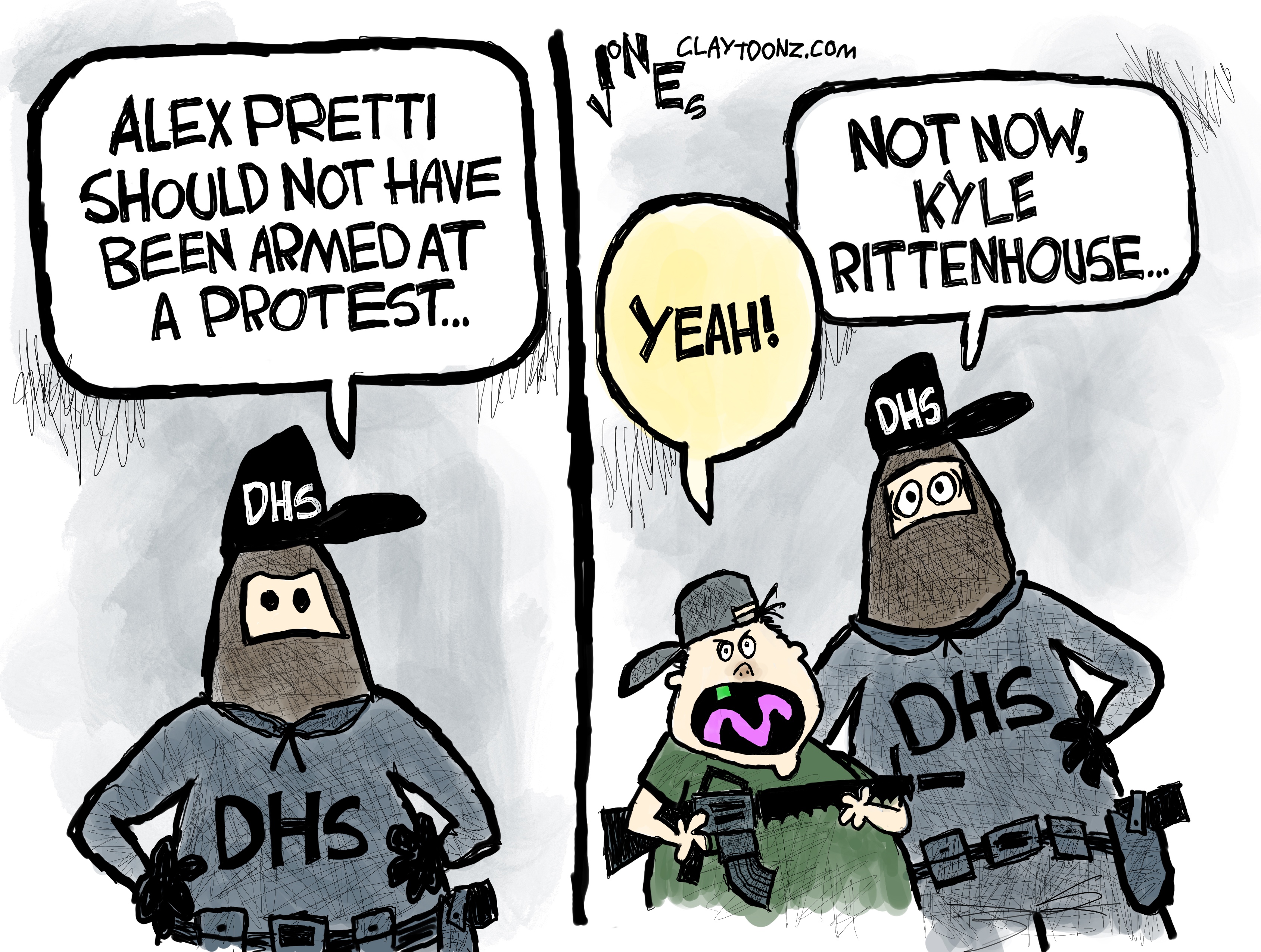

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more