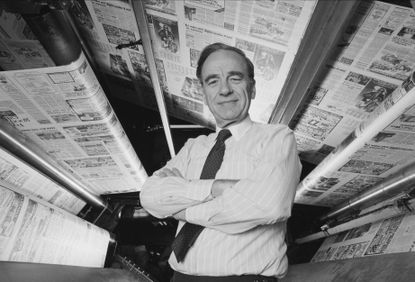

The Rupert Murdoch succession: Why 21st Century Fox may have a 'great man's progeny' problem

Is James Murdoch really the best qualified to lead 21st Century Fox?

It's the end of an era, folks: Rupert Murdoch is stepping down as chief executive officer of 21st Century Fox.

According to CNBC, Murdoch's son James Murdoch will take over the role of CEO. The patriarch himself will remain as the executive chairman — essentially the point man for the corporate board of directors. Murdoch's other son, Lachlan Murdoch, will remain as co-chairman.

It's not entirely clear how much this will change strategy at Fox in substantive terms — Rupert Murdoch still boasts a commanding 39.4 percent of the company's voting shares. "No one doubts the elder Murdoch will still have the final say on whatever goes on at Fox," wrote CNBC's David Faber, but "the change at Fox is clearly an acknowledgement that the next generation of Murdochs is ready to take its place in leading the media giant."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With the expected departure of Chief Operating Officer Chase Carey sometime after 2016, the company will also be "without a layer of senior management outside the family for the first time."

At first blush, this all seems natural. Rupert Murdoch is well into his eighties. Of course his son would step in to take over the family business at some point!

Except it doesn't really make sense to call 21st Century Fox a "family business." Sure, Murdoch founded it. But it's also a massive, publicly traded media empire — the sort of corporate behemoth that's supposed to exemplify the rational economic benefits of competition and the profit motive.

It would actually be quite a coincidence if the person best suited to ensure the ongoing soundness of Fox's business model also happened to share Murdoch's DNA.

On Wednesday, law professor Steven Davidoff Solomon had an interesting piece in The New York Times on J. Crew, another corporate behemoth going through a bit of a shake-up. The company is facing struggling revenue, poorly performing merchandise, and a brand that doesn't command the respect it used to. And a lot of that seems to stem from an ill-fated decision to take the company private in 2011, which was rammed through by J. Crew CEO Millard Drexler.

Solomon calls this the "great man" problem. Despite problems with the deal, other players in J. Crew were willing to chain themselves to Drexler's plan because, well, he was the one who built up the company while CEO. Another course of action might have seemed prudent from the standpoint of cold-eyed analysis. But Drexler's sheer clout overwhelmed such considerations.

You could say that the younger Murdoch's rise to the top of 21st Century Fox illustrates a potential "great man's progeny" problem. Just as sticking with Drexler seemed like an inevitability in the context of J. Crew's internal culture, the transfer of legacy from one generation to the next may have struck Fox's internal culture as inevitable as well, despite James Murdoch's past missteps.

As Faber reminds us, James Murdoch "gave up his job running BSkyB after the U.K. hacking scandal engulfed the company four years ago." Faber says that James has since "been winning fans among the Fox investor base for his work as co-COO," and that they "believe James has matured as a leader, has a detailed knowledge of the company's operations, and is the driving force behind its expansion in digital distribution."

That's not damning. But "matured as a leader" is hardly a ringing endorsement, either. So far, the Murdoch empire's forays into the digital world have been the one decidedly lackluster aspect of its business efforts.

And the hacking scandal is an illuminating story. That was when British reporters in Rupert Murdoch's newspaper operations were caught hacking the phones of politicians, celebrities, and crime victims. James Murdoch didn't take over as executive chairman of News of the World — the tabloid where the hacking took place — until 2007, about a year after the hacking occurred. But the British government still criticized him for failing to properly inquire into what happened.

News Corporation, Rupert Murdoch's umbrella company, owned about 40 percent of BSkyB at the time, and James was chairman. But after the scandal broke, News Corporation dropped plans to acquire the rest of BSkyB, a huge setback. (Later, News Corporation was split into News Corp (which kept the publishing business) and 21st Century Fox (which kept the far more lucrative media, television, and movie business).)

The British report also criticized the business culture Murdoch the elder had fostered. So it's altogether possible that the Murdoch clan and their apparatchiks at 21st Century Fox view the hacking scandal more as a kind of communal trial-by-fire, than as any reason to wonder if James Murdoch's ascension is the best idea from a business standpoint.

News Corp and 21st Century Fox are both U.S.-based. And one of the under-appreciated aspects of American corporate law is the way it actually muddles or even entirely hamstrings the ability of genuine market forces to determine who sits on corporate boards and who sits behind the CEO's desk. In many ways, voting shareholders, corporate boards, and corporate management all constitute a kind of traveling community unto themselves, often impervious to any consequences from their business decisions.

If you listen to the way the commentariat talks about modern business and the free market, competition is supposed to unleash rational forces that push back against the emotional and achingly human fixations on kinship circles, tribal affiliation, generational legacy, and the like. But the ironic truth is that the rise of the modern mega-corporation may have simply given those very old forces a much bigger stage to play out on.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

5 hilariously spirited cartoons about the spirit of Christmas

5 hilariously spirited cartoons about the spirit of ChristmasCartoons Artists take on excuses, pardons, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Inside the house of Assad

Inside the house of AssadThe Explainer Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, ruled Syria for more than half a century but how did one family achieve and maintain power?

By The Week UK Published

-

Sudoku medium: December 22, 2024

Sudoku medium: December 22, 2024The Week's daily medium sudoku puzzle

By The Week Staff Published