Why Twitter is terrible

Blame an age-old idea known as "comprehensive doctrines"

"There's no way around it," I tweeted in September. "Twitter is getting markedly worse. I'm nervous." Since then, the world has caught up. Celebrities have gone dark. Kids have moved to Snapchat. The scarred and the scared have locked down their accounts. Twitter's CEO Dick Costolo has been hounded out of office.

But these are all symptoms, not the sickness. Business critics say Twitter is falling because the suits don't know what do to with the service. In reality, it's failing because our social mobs know just what to do with it. Twitter is getting worse because it helps us argue — and believe — that everyone else is getting worse.

Twitter is commonly understood to have become defined by aggressive, incessant performances of identity. This is, by and large, true — but blaming identity politics only goes so far.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On Twitter, we're not screaming at each other because we want to put different identities on cyber-display. We're doing it because we're all succumbing to what philosophers call "comprehensive doctrines." Translated into plain language, comprehensive doctrines are grandiose, all-inclusive accounts of how the world is and should be.

The debasement of Twitter indicates that many of us are ready to slip into verbal brutality to show that just one worldview — ours, of course — can annihilate the competition. Twitter used to be a place to escape from the uniformity and hyperventilation of the "mainstream media," where the ideological id has long run rampant. Now, Twitter is a megaphone for the worldview wars. It fosters constant competition among our claims that everyone should care and act as we do.

Consider how our humanity shows forth when we're actually required to deal with each other in person. When we're stuck facing others in the flesh in order to assert our identity, our ability to use doctrine as a sword and a shield dramatically weakens. Habituated to living and working with our neighbors, we don't see them as disembodied portals spewing demands. We see them as humans.

There's always some risk of romanticizing our prospects for face-to-face collaboration. But on Twitter, we're cultivating an active contempt for that kind of political small ball, because the place for such modest and unassuming activity is so small. It doesn't get retweets. It doesn't drive clicks. It can't start memes. Comprehensive doctrines are much more relevant and buzzworthy. By turning ourselves first and foremost into their foot soldiers, we, too, become more relevant and buzzworthy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At least, that's the hope. But is it ever enough? Is there ever victory? Despite the hardening of our worldviews, we have increasingly grown skeptical of the idea that little groups of people can overcome vast structural problems. And on closer inspection, lots of those structural problems turn out to be… other people's comprehensive doctrines. In a vicious circle, our mutual respect wanes as our worldviews grow more merciless.

It would be one thing if we could redeem all society by leaving Twitter. But Twitter is just the beginning. We could "burn down the internet," as the kids say, and still fail to calm our blind rage toward our all-too-human imperfection and intransigence. At this rate, maybe we will.

Two hundred years ago, another liberal philosopher explained how merciless worldviews can destroy all communication. "The nation could survive for a while," warned Benjamin Constant, "on its acquired intelligence, on habits of thinking and doing picked up earlier; but nothing in the world of thought would renew itself. Writers strangled in this way start off with panegyrics; but they become bit by bit incapable even of praise and literature finishes up losing itself in anagrams and acrostics." Sound familiar?

It may be too late to salvage Twitter. But if we're going to save the internet, we've got to save some mercy for one another.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

Jane Austen lives on at these timeless hotels

Jane Austen lives on at these timeless hotelsThe Week Recommends Here’s where to celebrate the writing legend’s 250th birthday

-

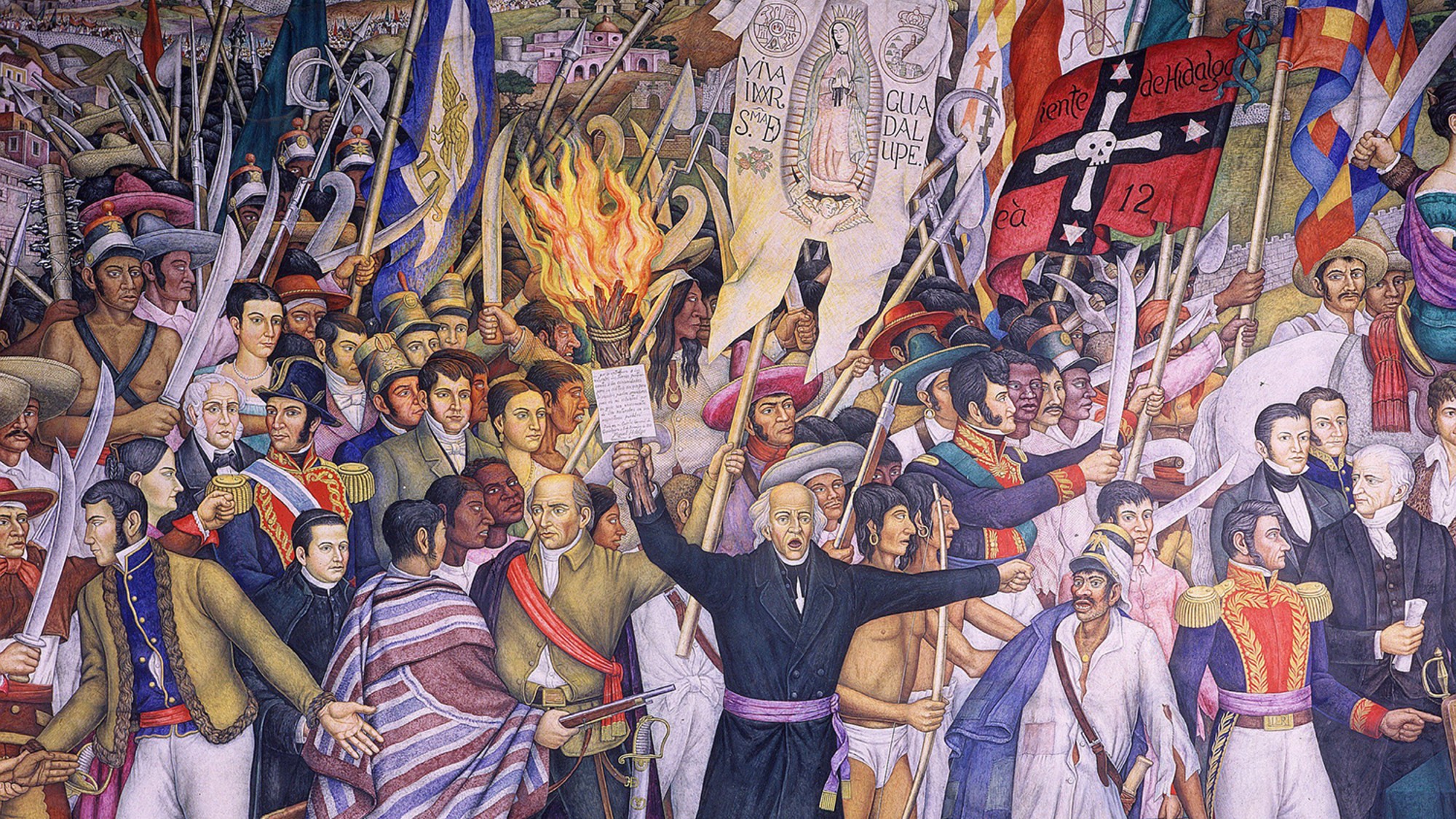

‘Mexico: A 500-Year History’ by Paul Gillingham and ‘When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy’ by David Margolick

‘Mexico: A 500-Year History’ by Paul Gillingham and ‘When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy’ by David Margolickfeature A chronicle of Mexico’s shifts in power and how Sid Caesar shaped the early days of television

-

GOP wins tight House race in red Tennessee district

GOP wins tight House race in red Tennessee districtSpeed Read Republicans maintained their advantage in the House