America's embassy in Cuba never really closed

Here's the strange history of America's six-story Modernist compound in Havana

On Friday, the three U.S. Marines who lowered the American flag for the last time at the U.S. Embassy in Havana 54 years ago will raise the flag again over the reopened embassy. Secretary of State John Kerry, officials from the Pentagon and other U.S. departments, and eight members of Congress will also be there, the highest-ranking delegation to Cuba in 70 years. "We're doing something that not too many Marines have ever done," one of the now-retired Marines, Larry Morris, 75, tells The New York Times. "It's thrilling."

Morris and the other two Marines, James Tracy (now 78) and Mike East (76), had just spent hours incinerating piles of government documents when they went out to lower the flag on Jan. 4, 1961. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in one of his last acts in office, had just severed diplomatic relations with Cuba, and Fidel Castro had given the U.S. 48 hours to vacate the island and the embassy, a six-story Modernist building in a compound across the street from the ocean along Havana's Malecón.

This is how the embassy, opened in 1953 and designed by U.S. firm Harrison & Abramovitz, looked in 1973, according to a pictorial history in Architect Magazine:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And here's how it looked in 2001, after renovations completed four years earlier:

And leave America did. From 1961 until 1977 — when President Jimmy Carter negotiated a slight thawing of relations and opened the "U.S. Interests Section" in Havana (while Cuba opened a "Cuban Interests Section" in Washington) — the U.S. had no diplomatic presence in Cuba.

But the U.S. Embassy didn't close, exactly, and it didn't lie vacant for 16 years. On Jan. 7, 1961, U.S. chargé d’affaires Daniel Braddock handed the keys over to the Swiss embassy in Havana, and the Swiss held on to the building and the ornate 35,000-square-foot U.S. ambassador's residence until America returned in 1977.

That wasn't an easy job, according to Swiss historian and political scientist Thomas Fischer. When the U.S. cut diplomatic ties to Cuba in 1961, it asked Switzerland to represent its interests as a protecting power. (The U.S. Interests Section continued to be under Switzerland's protection until July 20, when the U.S. and Cuba officially restored diplomatic ties. Cuba's interests in Washington were initially protected by Czechoslovakia.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the 16 years that the Swiss were America's sole diplomatic stand-in in Cuba, Castro threatened to nationalize and take over the embassy building at least twice, Fischer wrote in a 2010 research paper at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. The first time was in February 1964, when the Swiss ambassador was a gifted diplomat named Emil A. Stadelhofer.

The Cubans had originally approached Stadelhofer informally in late 1963 to feel him out on the possibility of nationalizing the former U.S. embassy or at least leasing it, Fischer writes. Stadelhofer said no way, "referring to the absolute character of Article 45 of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961, strictly prohibiting such a step by the host government. He even stated that this would potentially be considered by Swiss authorities the most unfriendly and severest act against Swiss foreign policy since the existence of the Confederation."

But after the U.S. confiscated four Cuban fishing vessels off Key West on Feb. 2, 1964, Havana pressed the issue. Citing historian W.S. Smith, Fischer recounts that Cuban officials "appeared at the entrance of the former U.S. Embassy in Havana, determined to take possession of the building for the purposes of the Cuban Ministry of Fishing." He continues:

Ambassador Stadelhofer was only just... able to prevent this measure by barring the door and declaring that this was diplomatic property, and would be violated only over his body. Apparently, in the end, the Cubans relented and no further efforts were made to seize the building at the time. [Fischer]

Two years later, Fischer notes, the Swiss had about 50 people working in the U.S. Embassy, with much of their energies dedicated to processing the requests of Cubans who wanted to emigrate to the U.S. in a massive airlift. But in 1970, when Alfred Fischli was Swiss ambassador, Cuba tried again.

A U.S.-based Cuban exile group called Alpha 66 had sunk two Cuban fishing boats and was holding their crews prisoner on a Caribbean island, prompting tens of thousands of Cubans to surround the U.S. Embassy building, trapping the Swiss embassy workers inside for three tense days. That incident ended peacefully when Alpha 66 released its prisoners, but the episode "triggered a renewal of the discussion on the ownership structure of the former U.S. Embassy building," Fischer writes, continuing:

Cuban authorities considered American claims on the premises as forfeited, and had only tacitly agreed to the use of the building by the Swiss protecting power in the past years. The most insistent démarches by the Swiss embassy referring to the rules of the Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic Relations were necessary to prevent the Cubans from another attempt to definitely occupy and [nationalize] the building in the circumstances. [Fischer]

Even when the U.S. flag is once again flying over the American Embassy in Havana on Friday, relations between Cuba and the U.S. won't exactly be normal. Old wounds heal slowly, and the Republican-led Congress doesn't seem eager to confirm an ambassador to Havana or end the decades-old trade embargo. But amid all the muted festivities of the historic occasion, it's worth taking a moment to thank the Swiss for making sure America still has an embassy to fly the Stars and Stripes above.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

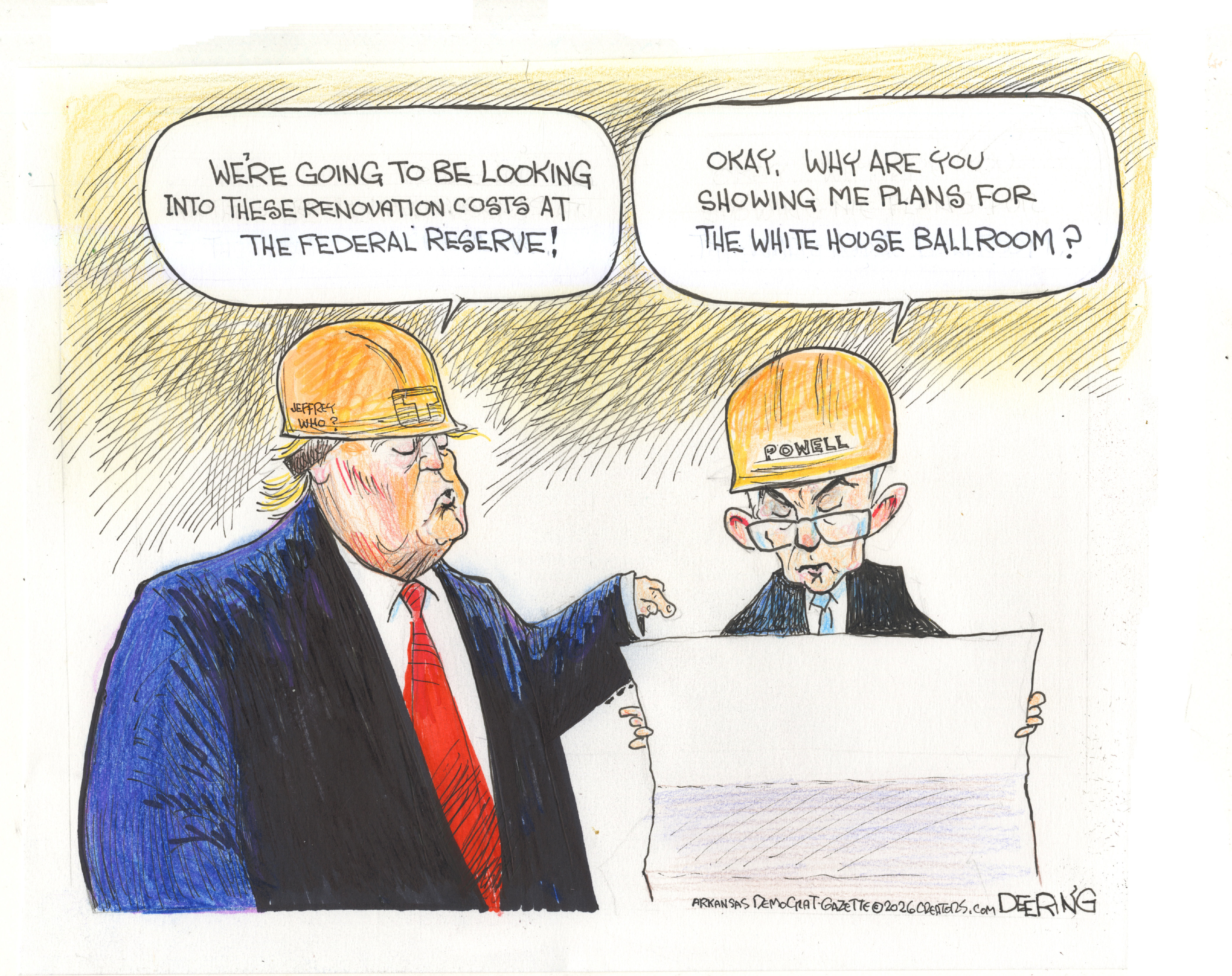

Political cartoons for January 17

Political cartoons for January 17Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include hard hats, compliance, and more

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

Why Puerto Rico is starving

Why Puerto Rico is starvingThe Explainer Thanks to poor policy design, congressional dithering, and a hostile White House, hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable Puerto Ricans are about to go hungry

-

Why on Earth does the Olympics still refer to hundreds of athletes as 'ladies'?

Why on Earth does the Olympics still refer to hundreds of athletes as 'ladies'?The Explainer Stop it. Just stop.

-

How to ride out the apocalypse in a big city

How to ride out the apocalypse in a big cityThe Explainer So you live in a city and don't want to die a fiery death ...

-

Puerto Rico, lost in limbo

Puerto Rico, lost in limboThe Explainer Puerto Ricans are Americans, but have a vague legal status that will impair the island's recovery

-

American barbarism

American barbarismThe Explainer What the Las Vegas massacre reveals about the veneer of our civilization

-

Welfare's customer service problem

Welfare's customer service problemThe Explainer Its intentionally mean bureaucracy is crushing poor Americans

-

Nothing about 'blood and soil' is American

Nothing about 'blood and soil' is AmericanThe Explainer Here's what the vile neo-Nazi slogan really means

-

Don't let cell phones ruin America's national parks

Don't let cell phones ruin America's national parksThe Explainer As John Muir wrote, "Only by going alone in silence ... can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness"