Rebirth and resentment in New Orleans

Amid an influx of money and newcomers, some locals worry about the city's soul

ON THE "SLIVER by the river," the stretch of precious high ground snug against the Mississippi, tech companies sprout in gleaming towers, swelling with 20-somethings from New England or the Plains who saw the floods only in pictures.

A new $1 billion medical center rises downtown, tourism has rebounded, the music and restaurant scenes are sizzling, and the economy has been buoyed by billions of federal dollars.

New Orleans is now swaddled in 133 miles of sturdier levees and floodwalls, and it boasts the world's biggest drainage pumping station. But on the porch stoops of this place so comfortable with the cycles of death and decay, they still talk about living in some kind of Atlantis-in-waiting. As if the cradle of jazz might still slip beneath the sea.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ten years after Hurricane Katrina slashed and snarled into New Orleans, on Aug. 29, 2005, newcomers take their juice with chia seeds and buy fixer-uppers, and longtime locals fret that the city is no longer theirs, that it's too expensive and might lose its soul. A city some feared might be left for dead when 80 percent of its footprint was submerged is undergoing a social, economic, and cultural evolution. Yet it is still a place deeply tied to its ancient traditions and rites, stubbornly and proudly unique.

In the Lower Ninth Ward and in eastern New Orleans, the shells of houses wrecked by Katrina still rot in the humidity, caved-in roofs and teetering walls sharing blocks with homes that got put back together, lifted onto concrete stilts, and reinhabited.

Yet the city's very survival as an inviting and vibrant space has made it into a symbol of resilience, an inspiration for other places savaged by nature's whims and man's mistakes. And the intractability of some of its problems — some of which existed before the storm but have worsened or stagnated since — has made it a magnet for the world's tinkerers, thinkers, and doers.

"I say New Orleans is the nation's most immediate lab for innovation and change," Mayor Mitch Landrieu observes one afternoon. "Some people call that an experiment, some a lab. We call it necessity."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The suggestion that New Orleans is a petri dish sits uncomfortably with some people. The long-term impact of the conversion of its schools to an all-charter system and the decision to demolish large public housing developments in favor of new mixed-use housing will be debated for years.

The rising cost of living has flipped some of the city's neighborhoods from majority black to majority white. Rents have soared, and by one estimate, home sale prices have climbed more than 40 percent in 10 years.

But the people who now populate the city aren't necessarily the ones who fled it. "The Chocolate City" that the bungling and corrupt Katrina-era mayor, Ray Nagin, famously described in the wake of Katrina is still majority black, but its African-American population has shrunk by nearly 100,000 — to 59 percent from 67 percent.

African-Americans who have returned have also been less likely to share in the abundance. The gap between the median income of blacks and whites grew by 18 percent after the storm, and the number of African-American children living in poverty jumped from 44 percent to more than 51 percent.

ON URSULINES AVENUE in the Tremé neighborhood, there's a pretty little side-hall shotgun house with olive trim and a porch painted red.

Buying that house in a neighborhood that embodies the African-American culture of New Orleans, a place where they send off the dead from Charbonnet Funeral Home with trombones and trumpets, high-stepping and buck-jumping, came with a tangle of emotion for Jen Medbery, a child of Connecticut.

Medbery, one of the standouts in a post–Hurricane Katrina wave of successful tech entrepreneurs, and her husband are the only white residents on their block, and she's acutely aware of what that means: "I am a gentrifier," Medbery, 31, says.

The presence of outsiders like her "is shifting the dynamic of what New Orleans is," says Medbery, who fell hard for the city in her mid-20s while teaching at a charter school in the early years after Katrina and now runs an education software company.

Five minutes down the road, at the opposite end of Tremé, Dianne Honore, 50, rented half of a brick double across from Louis Armstrong Park a couple of years back. Honore, a licensed practical nurse, is one of the New Orleans Baby Dolls, a group of women who march during Carnival season as part of a tradition that dates back to the defiant side-street parades of segregation-era black prostitutes.

Honore's landlord called a few weeks ago to tell her she had to go. The house was going to be sold. Honore, who lived in Texas after being flooded out, just "got gentrified," six years after coming home, she says. "Some days, you feel like your culture is still drowning."

On the Friday before Mardi Gras, Patrick Comer and 150 of his friends, entrepreneurs all, spilled out of Arnaud's, a venerable French Quarter restaurant, and onto Bourbon Street. The Friday luncheon is a Carnival season tradition. In another era, Comer — founder of Federated Sample, a digital market-research company — might have been angling to join one of the city's old-line krewes, or Carnival societies. It might have been his entrée into the social and business upper crust.

But Comer, a 41-year-old Alabamian, hasn't bothered. He and other investors — many from out-of-state, but some upstart locals, too — have launched their own Carnival society. They call it the Krewe du Nieux, which is pronounced "new" — precisely the identity and message they hope to transmit to the world.

Investors have taken notice of the influx, pumping money into New Orleans startups. Forbes recently named New Orleans "America's biggest brain magnet." The city saw startups launched at a 64 percent higher rate than the national average from 2011 to 2013, according to the Data Center, an independent research group.

New Orleans as a magnet for "nieux" business would have sounded like fantasy a decade ago. "It was a very insular community that was scared of new people," said Tim Williamson, a New Orleans native who runs a business incubator called Idea Village. "The day after Katrina, everybody became an entrepreneur."

KEITH WELDON MEDLEY smiled at first. It looked so charming, all those people driving slowly down Burgundy Street through the Faubourg Marigny and Bywater neighborhoods, pointing cameras.

Then it dawned on him: These folks weren't tourists or architecture buffs. They were shoppers. And on their shopping list was almost everything that could be had in these neighborhoods — a collection of Creole cottages, shotgun doubles, warehouses, and small manufacturers at a humpback bend of the Mississippi River.

In the evolution of post-Katrina New Orleans, few phenomena have been more striking than the dramatic demographic shift of places such as Bywater from majority black to majority white. One census block group in Bywater dropped from 51 percent African-American before Katrina to just 17 percent afterward; the largest went from 63 percent to 32, according to an analysis of U.S. census data.

"You saw all these white people. Obviously they were displacing black people who were here before," said Medley, an African-American historian who lives in the Marigny house where he grew up.

Post-Katrina New Orleans feels like a "conundrum" to Medley: a city that is safer and more prosperous but emptied of many of the people he'd known for decades. "We have hipsters now," says Medley.

A few months ago, vandals broke windows and spray-painted "Yuppy = bad" on the nearby St. Roch Market, a shiny symbol of the New Orleans recovery that had been closed for years after it flooded. The market, which opened in 1875, sold po' boys and shrimp-by-the-pound in an atmosphere of rotting charm before Katrina; it now houses pricey food stalls.

And though the vandals were roundly condemned, they also sparked a conversation about the identity of the city post-Katrina, and particularly about the character of poorer neighborhoods. After Katrina, there was a rush to buy up properties in the sliver-by-the-river neighborhoods such as the Marigny and Bywater — anything that didn't flood.

Now, Robyn Halvorsen, a co-owner of the iconic Bywater bar Vaughan's, can walk down almost any street and point to houses where someone is gone.

Halvorsen's favorite neighbor was an old gentleman named Mr. Singleton; he was a stoop sitter, a constant in the Bywater neighborhood where she has lived for decades. He couldn't keep up with the taxes, she says, and sold his place.

Some people from up north bought it. They fixed it. They made it pretty. "They're nice," Halvorsen says. "But they're not stoop sitters."

OUT ON BENEFIT Street in the Upper Ninth Ward, there's a china ball tree where Mr. Phil's house once stood.

Now just a patch of grass, it's as good a spot as any to drink a beer on a Tuesday afternoon. But at night you wouldn't go near it. Night, says Earnest Lyons, an appliance repairman who lives nearby, is when "the zombies" come out, the crackheads of this troubled neighborhood bounded by canals and railroad tracks, northeast of the city center.

Up the road there's a set of concrete stairs that leads to nowhere. But someone lives across the street; there's a tricycle in the driveway and the air conditioner hums.

It goes on like this for block after block. An empty foundation next to a spruced-up place with bright, clean siding next to a sagging wreck with a hole in the roof next to a house with a brand-new deck.

Jesse Perkins, a 54-year-old sewer manager who grew up in the Desire public housing development, lives across the street from a large seniors' apartment complex that was devastated during Katrina and now sits 10 years later with caved-in roofs and smashed-out windows. He's gotten used to the sound of junkies rustling around inside; he'll never get used to the gunshots in the distance.

A city long plagued by violence hit a 43-year low in its murder rate in 2014, according to Mayor Landrieu's office. But this year, there's been a spike in violence, and the city registered its 100th murder nearly two months earlier than the year before.

"The city, on balance, is far better off than before Katrina," says the writer Jason Berry, who's accustomed to the nightly symphony of sirens that has spread beyond the poorest sections. "But it's still a break-your-heart kind of town."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

-

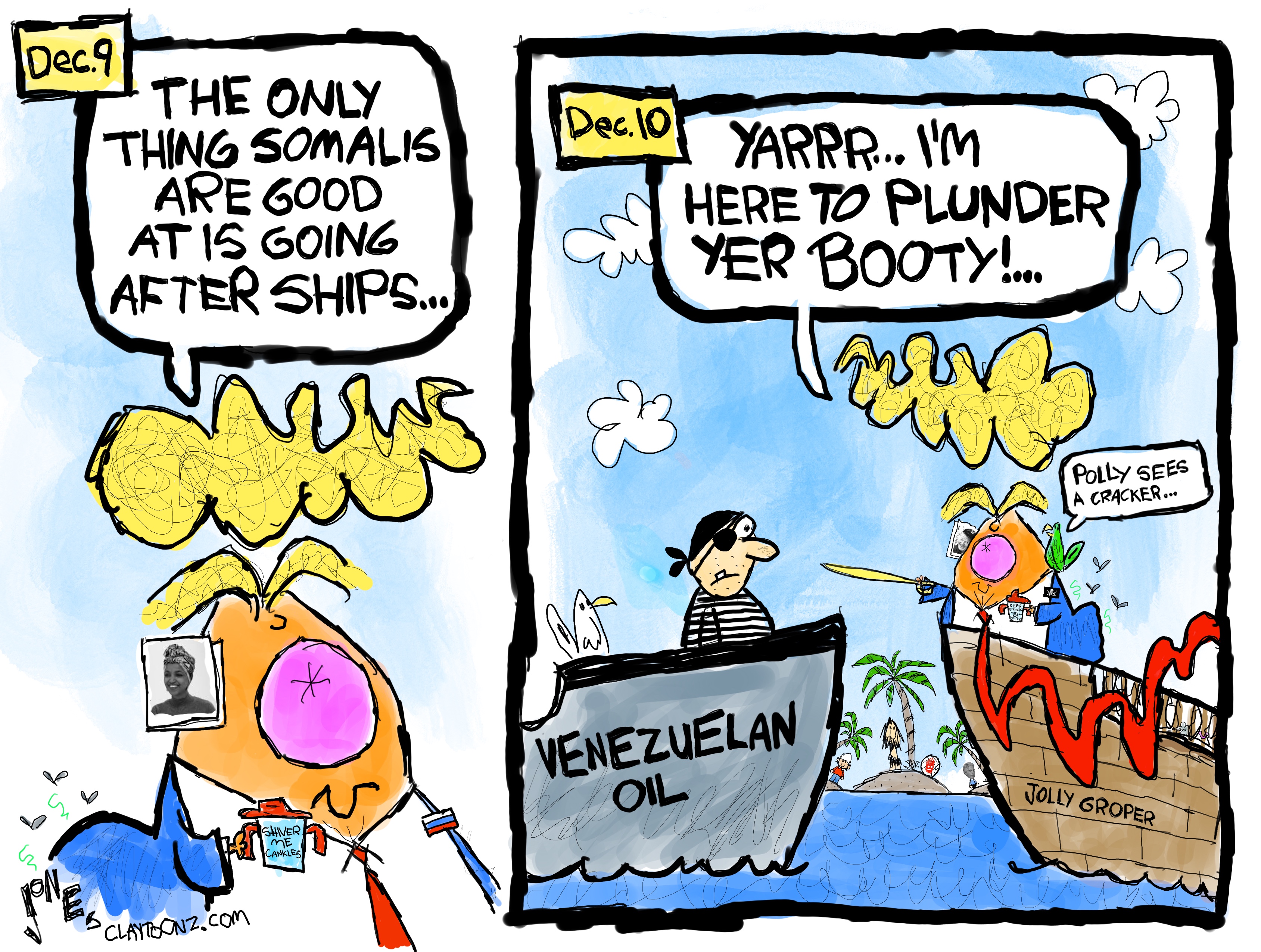

Political cartoons for December 12

Political cartoons for December 12Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include presidential piracy, emissions capping, and the Argentina bailout

-

The Week Unwrapped: what’s scuppering Bulgaria’s Euro dream?

The Week Unwrapped: what’s scuppering Bulgaria’s Euro dream?Podcast Plus has Syria changed, a year on from its revolution? And why are humans (mostly) monogamous?

-

Will there be peace before Christmas in Ukraine?

Will there be peace before Christmas in Ukraine?Today's Big Question Discussions over the weekend could see a unified set of proposals from EU, UK and US to present to Moscow