How Mexican drug cartels are fueling America's deadly heroin epidemic

It's starts with corporate-like discipline and the targeting of small cities like Dayton, Ohio

HE PRACTICED WITH baby carrots, swallowing them whole, easing them down his throat with yogurt. Later came the heroin pellets, each loaded with 14 grams of powder, machine-wrapped in wax paper and thick latex. Long gone were the days of swallowing hand-knotted, drug-filled condoms. The Mexican drug-trafficking organizations were always perfecting their craft.

On this trip, Gerardo Vagas would swallow 71 pellets — a full kilo, just over 2 pounds, enough for as many as 30,000 hits at $10 a pop on American streets. And so before he set off on his 3,900-mile journey from Uruapan, Mexico, Vargas had been given the rules: No soda, because it could erode the pellets' wrapping. No orange juice, either. Drink only water. He was told which airports to avoid, his every move orchestrated by his handler in Mexico.

And don't eat anything, he was told, until reaching the final destination: Dayton, Ohio, one of the new frontiers of the American heroin epidemic.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A sophisticated farm-to-arm supply chain is fueling America's surging heroin appetite, causing heroin to surpass cocaine and meth to become the nation's No. 1 drug threat for the first time. As demand has grown, the flow of heroin — a once taboo drug now easier to score in some cities than crack or pot — has changed, too.

Mexican cartels have overtaken the U.S. heroin trade, imposing an almost corporate discipline. They grow and process the drug themselves, increasingly replacing their traditional black tar with an innovative high-quality powder with mass market appeal: It can be smoked or snorted by newcomers as well as shot up by hard-core addicts.

They have broadened distribution beyond the old big-city heroin centers like Chicago and New York to target unlikely places such as Dayton. The midsize Midwestern city today is considered to be an epicenter of the heroin problem, with addicts buying and overdosing in unsettling droves. Crack dealers on street corners have been supplanted by heroin dealers ranging across a far wider landscape, almost invisible to law enforcement. They arrange deals by cellphone and deliver heroin like pizza.

In August 2014, a window opened into this shadowy world: A tip led federal drug agents to Vargas, a low-level courier willing to tell them what he knew in exchange for leniency. "Sometimes," one agent later explained, "the dope gods smile."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

VARGAS WAS THE perfect drug mule. He was 22 but looked younger. He'd been born in California, moving to Mexico at age 12 after his father was deported, so he possessed a U.S. passport. He also had a spotless record, perfect English, and a desperate need for cash: His father had already lost one eye to diabetes. He'd been offered $6 a gram. This job would earn him nearly $6,000.

Things could go wrong. Another courier headed to Dayton had to use the bathroom unexpectedly during a layover at a U.S. airport and lost his pellets when the toilet flushed automatically, according to the drug agents who finally arrested him.

Pellets bursting is a courier's worst fear. Once in Lorain, Ohio, a courier started foaming at the mouth, and his handler called down to Mexico to figure out what to do. As authorities listened via wiretap, the handler was told to cut the courier open and retrieve the remaining drugs.

This wasn't supposed to happen with heroin. The drug has a reputation as a rough ride, and for years, treatment centers saw few heroin addicts. But that started changing in the mid-2000s and took off a few years later after a government crackdown on opioid painkiller abuse. Unable to get pills, many addicts turned to heroin, the painkillers' chemical cousin.

Today, authorities estimate there are between 435,000 and 1.5 million heroin users in the United States. Treatment centers are once again flooded with young users, many of whom got their start on prescription drugs.

In Montgomery County, home to Dayton, heroin-related deaths have skyrocketed 225 percent since 2011. Last year, this county of 540,000 residents reported 127 fatal heroin overdoses — one of the highest rates in the nation.

"The coroner can't keep up," said Robert Carlson, a Wright State University ethnographer who helps track overdoses. "There's not enough room to keep all the bodies."

Just as U.S. authorities were cracking down on painkillers, Mexican cartels were figuring out how to make high-quality powder heroin. For decades, Mexicans dealt primarily in homegrown black tar heroin, a crude concoction that looks like its name. It is sticky like tree sap and odorous like vinegar. Its appeal is limited. And it was sold almost exclusively west of the Mississippi River. East of the Mississippi, the Colombians pushed powder heroin.

But moving beyond black tar made sense for the Mexicans. Powder was a better product. Stronger. It was easier to smuggle, too: Kilo for kilo, powder took up less room.

It was also extremely profitable. A kilo of heroin might cost $5,000 to produce in Mexico. But it could sell for $80,000 to suppliers in the U.S., twice what cocaine fetches. And a street dealer could make $300,000 by diluting the kilo and doling it out to addicts a 10th of a gram at a time.

For the drug cartel La Familia Michoacana, shipping powder straight to smaller markets such as Dayton meant no more sharing with suppliers in Chicago or New York.

"I'd never have thought it, but we turned into a source city," Montgomery County Sheriff Phil Plummer said.

To spur demand, dealers started throwing in free "tester" hits of powder heroin when customers bought pot or crack. Many dealers soon moved to heroin full-time, police and former addicts said.

WITH A BELLYFUL of heroin, Vargas followed the same worn path followed by hundreds of other drug mules. He began by hopping a 2:05 p.m. flight from Uruapan to Tijuana, putting him 20 minutes from the U.S.-Mexico border.

No one knows how many tons of drugs slip across that border. Authorities only know what they manage to stop. Researchers believe the detection rate hovers around 1.5 percent — favorable odds for a smuggler.

The next morning, Vargas and his kilo walked into the San Ysidro border station, the nation's busiest entry point. Waved on, he caught a hired van outside the border station and headed 100 miles north to John Wayne Airport in Santa Ana, California, bypassing the much closer airport in San Diego, which he'd been warned to avoid. Other drug couriers had been arrested there.

He caught AirTran Flight 436 to Las Vegas, then jumped on Southwest Flight 2419. But he wasn't flying to Dayton. He'd been warned to avoid that airport, too. He landed in Indianapolis at 1:19 a.m.

In the pre-dawn hours, Vargas hailed a cab for the two-hour ride to Dayton.

After 3,900 miles and 37 hours, Vargas checked into a $45-a-night room at the Dayton Motor Motel. He was in Room 8.

On the streets, heroin is called girl. Crack is boy. And the switch from boy to girl has complicated the job for drug cops like Sgt. John Sullivan, who heads Dayton's undercover drug unit. "In the transition from crack to heroin," said Sullivan, "the business model has totally changed."

The crack trade at least had a physical location. There were crack houses. Drug corners. Runners. Police knew which neighborhoods to focus on.

With heroin, it's mobile phones and car-to-car transactions. The deals can take place in mall parking lots. At gas stations. In suburbs. Dealers will come to you, what's known as the pizza-delivery model.

"There's no geography to it anymore," said Lee Hoffer, an ethnographer at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland who is studying heroin users. And the dealers have gotten smarter.

Tired of losing personal vehicles to drug forfeiture laws, they use rentals, which can't be seized, Sullivan said. The end of drug houses means there is nothing for police to raid — or rival dealers to rob. Turf wars have disappeared along with the turf. Drug dealers realized they could live anywhere. Some moved out to the suburbs. One moved into the same upscale apartment building as Sullivan.

The business now is all about the phone. A drug dealer's phone, filled with customers' numbers, is so valuable that it's known as a money phone. The information is often backed up onto other phones or stored on computers in Mexico. When police seize a money phone, they have to seal it in a special bag to block cell signals, so dealers can't erase its memory remotely.

"Logistically," said Capt. Mike Brem of the Montgomery County Sheriff's Office, heroin "is a nightmare."

THE AFTERNOON AFTER he arrived, Vargas emerged from his motel room. He walked across the parking lot, never seeming to notice the undercover drug cops parked around the perimeter The next afternoon, Jason Via, a DEA special agent, and another agent knocked on Vargas' door. Vargas did not seem surprised. He let them in.

Via noticed a trash can that had been used as a toilet — a sign of a body courier. Vargas permitted the agents to search the room. They found a plastic bag filled with heroin pellets hidden in the toilet tank.

Vargas began to talk. He told his life story. How he was a married father of two. How his father was sick with diabetes.

Then Vargas mentioned that he had one last pellet inside him. Via rushed Vargas to the hospital. He didn't want the pellet to burst.

Vargas faced serious prison time: 10 years to life. His best shot at helping himself was to talk. So he spilled the details of his trips. It was clear how little Vargas knew. "He was a babe in the woods," his attorney, Patrick Mulligan, said.

At his sentencing in January, Vargas was remorseful. The judge gave him two years.

Recently, county detectives were closing in on another courier holed up in another local motel. This time, the courier was a woman, as many are these days, a fresh sign of the ever-changing tactics.

But the dope gods were not smiling this time. They just missed her.

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

-

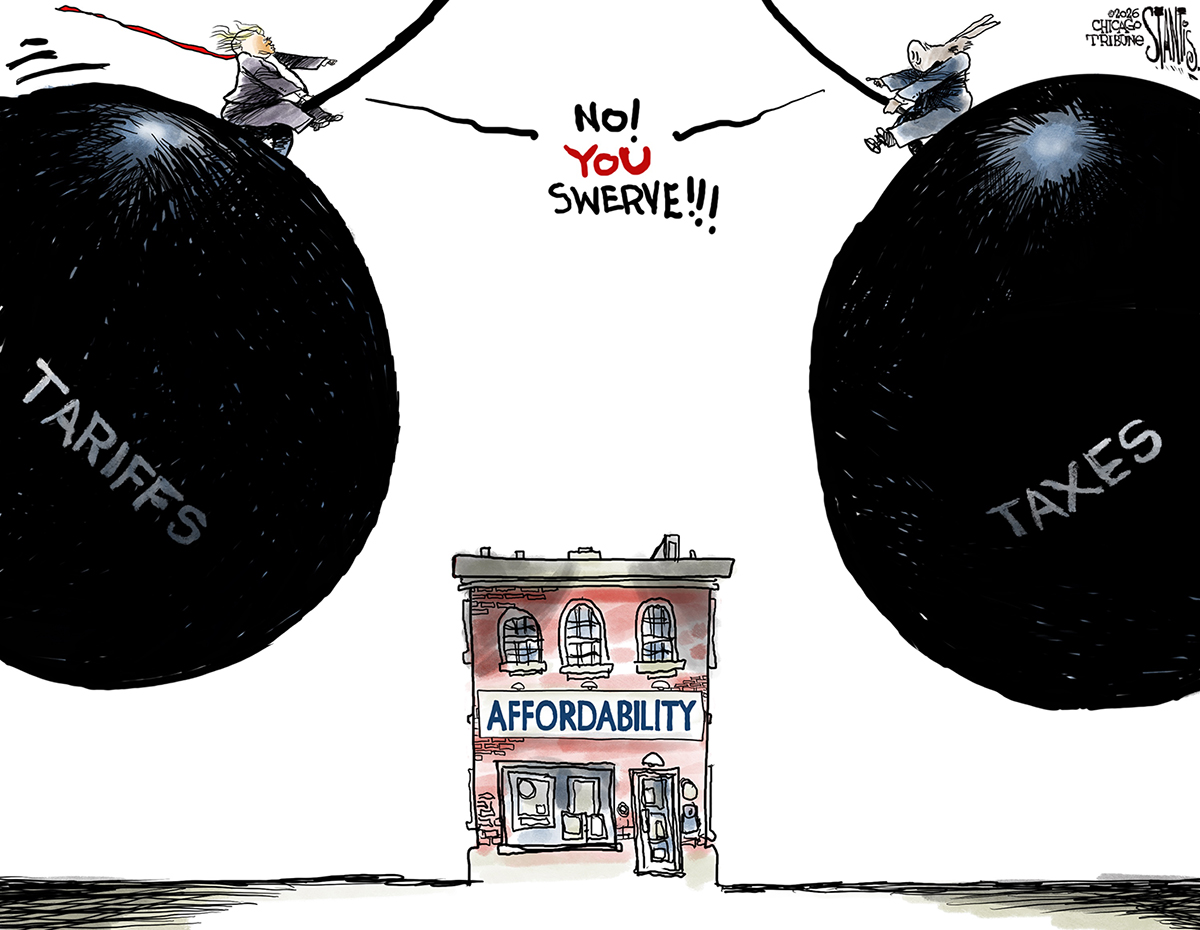

Political cartoons for January 18

Political cartoons for January 18Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include cost of living, endless supply of greed, and more

-

Exploring ancient forests on three continents

Exploring ancient forests on three continentsThe Week Recommends Reconnecting with historic nature across the world

-

How oil tankers have been weaponised

How oil tankers have been weaponisedThe Explainer The seizure of a Russian tanker in the Atlantic last week has drawn attention to the country’s clandestine shipping network