The great Budweiser-ization of the global beer market

How big beer-brewing companies keep getting bigger

In the dystopia of the future, we will buy everything from Amazon, Facebook will be the internet, and the world will drink nothing but Budweiser.

Or that's how it will play out if Belgium-based Anheuser-Busch InBev has anything to say about it. The company — often referred to as AB InBev — is the home of brands like Budweiser, Corona, and Stella Artois. And on Tuesday, it inked an initial deal to buy its British rival, SABMiller, adding the likes of Miller Lite, Peroni Nastro Azzuro, Pilsner Urquell, and Grolsch to its arsenal. The combined beer-making behemoth would control just over 30 percent of the world market by volume, and almost 60 percent of global profits in the industry.

But the deal may well face some pushback stateside. "Analysts say it is likely that the United States Justice Department will seek the breakup of MillerCoors," The New York Times reported. That's the joint operation SABMiller and Molson Coors created in 2008 to push brands like Miller Lite, Coors Lite and Blue Moon in the American market. So the goal of the Justice Department's Antitrust Division would be to safeguard competition in the U.S by forcing the new AB Inbev-SABMiller combo to spin off part of its U.S. operations. A similar arrangement was brokered in 2013, when SABMiller bought the Mexico-based Grupo Modelo, and the Justice Department forced them to sell off the latter's U.S. business.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But in truth, even if the Antitrust Division gets what it wants — and it's already a shadow of its former self — it probably won't matter much to AB InBev and SABMiller.

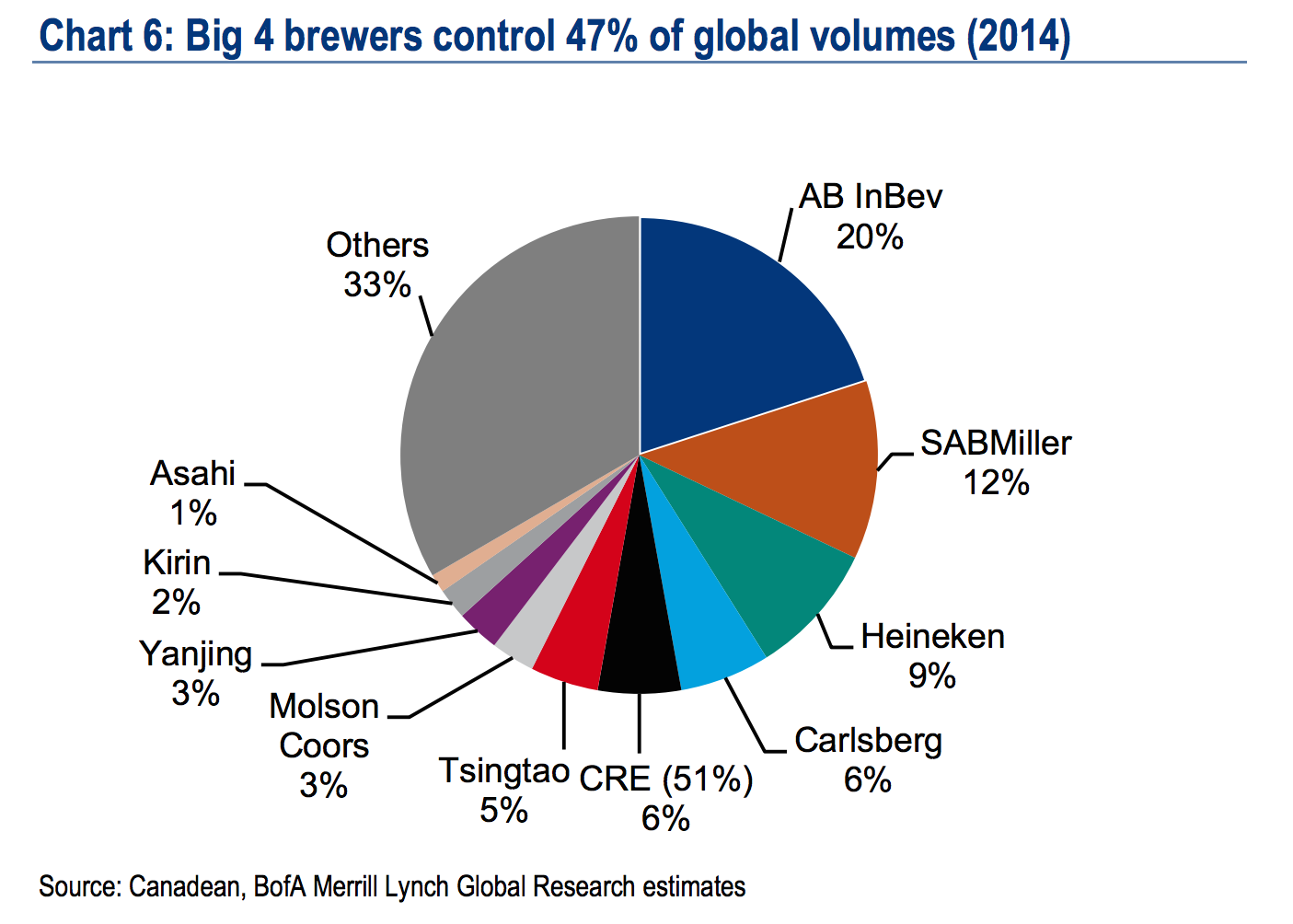

To understand why, first take a closer look at the global beer market:

(Graph courtesy of Business Insider.)

Four companies — AB InBev, SABMiller, Heineken, and Carlsberg — controlled 47 percent of the world market by volume in 2014, and accounted for 74 percent of its profits. There's also been an extraordinary amount of change and consolidation: As recently as 2004, 10 different brewers controlled 51 percent of the global market by volume.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

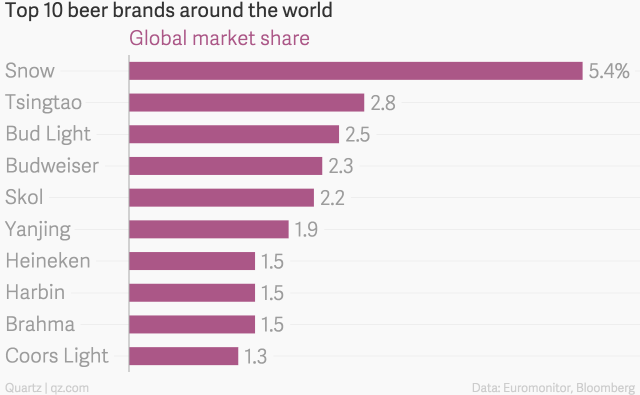

But you need to combine that graph with this one, which shows market share by beer brand:

(Graph courtesy of Quartz.)

As you probably noticed, the top two are not familiar to Americans. Snow and Tsingtao are both Chinese brands. And in fact, China is the biggest beer market in the world by volume, and has been since 2002. That's when China passed the U.S. for the top slot, and it's now twice as large. America is still the biggest market by sales, but China is catching up fast there as well: In 2013, its market by sales was 79 percent the size of the American market, once you translate both into fixed U.S. dollar exchange rates. And Euromonitor International is projecting the Chinese market will grow 45 percent by 2017, launching it into the top spot by that metric, too.

But here's the final gag that brings this all together: Snow is a SABMiller beer.

It owns the brand along with China Resources Enterprise. (AB InBev used to own a big chunk of Tsingtao too, though it recently sold off the last of its stake.) That kind of joint ownership is actually pretty common in China, because the government uses policy to actively discourage majority control by foreign companies. As of 2013, SABMiller was technically the fourth-largest brewer by volume sales, but it doesn't register as such in the official stats because its 49 percent ownership stake in Snow doesn't quite qualify it as the owner.

That's what this deal is really about. By combining with SABMiller, AB InBev will position itself in what is about to become the biggest beer market in the world. The same phenomenon is happening across the globe, as developing countries like India, Columbia, Peru, and others across Africa are bringing a flood of new consumers into the beer market. The United States simply isn't the main chess piece on the board anymore. The game is now about properly placing yourself to dominate the coming boom in the global beer market. So even if SABMiller and AB InBev are prevented from dominating the American market, that would likely have little impact on the grand strategy.

The other wrinkle here is the rise of craft beers. They're already 9 percent of the U.S. market by sales and 6 percent by volume. But they're nibbling around the edges in markets like China and Mexico as well. In fact, SABMiller's previous attempt to snatch up Grupo Modelo's American operations was a pretty clear effort to neutralize at least some of the competition coming from the smaller brewers.

Like other big companies pushing for monopoly power, the big beer companies have tended to engage in a kind of faux-competition, where no one wants to get into a price war, so you get a kind of collusion-by-default to keep prices high. It's not illegal, it's just the natural way markets break down when you've only got a small number of big players. But in the 2013 instance, Modelo was what antitrust lawyers and economists call a "maverick" — it wasn't playing along with the high prices, and was forcing competitive pressure on the big boys. That's why the Antitrust Division chose to protect it by forcing Grupo Modelo to give up its U.S. portion once SABMiller bought it out.

All of which makes it rather odd that some commentators are poo-poo-ing the need for antitrust regulators to get involved in the AB InBev-SABMiller marriage — or in the SABMiller-Grupo Model case before that.

Sure, the rise of craft breweries has been a wonderful development for beer fans, and the competition seems vibrant. And it's not clear how much preserving competition within U.S. borders would help the rest of the world. (China and India have burgeoning antitrust laws themselves, though it's unclear how or if they will be applied.)

But craft beers are also a geographically and socio-economically limited market, and 9 percent of sales isn't that much. If AB InBev and SABMiller get to go through with even their American combination, they'd control a dominating 70 percent of domestic beer industry profits.

It's certainly possible the combo wouldn't hurt competition. But it clearly couldn't help it. And preventing the merger, while it wouldn't necessarily help competition, obviously can't hurt it.

Better safe than sorry, it would seem.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.