A feminist among the centerfolds

In 1969, I naïvely accepted an assignment from Playboy to write about the women's lib movement. I should have known better.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

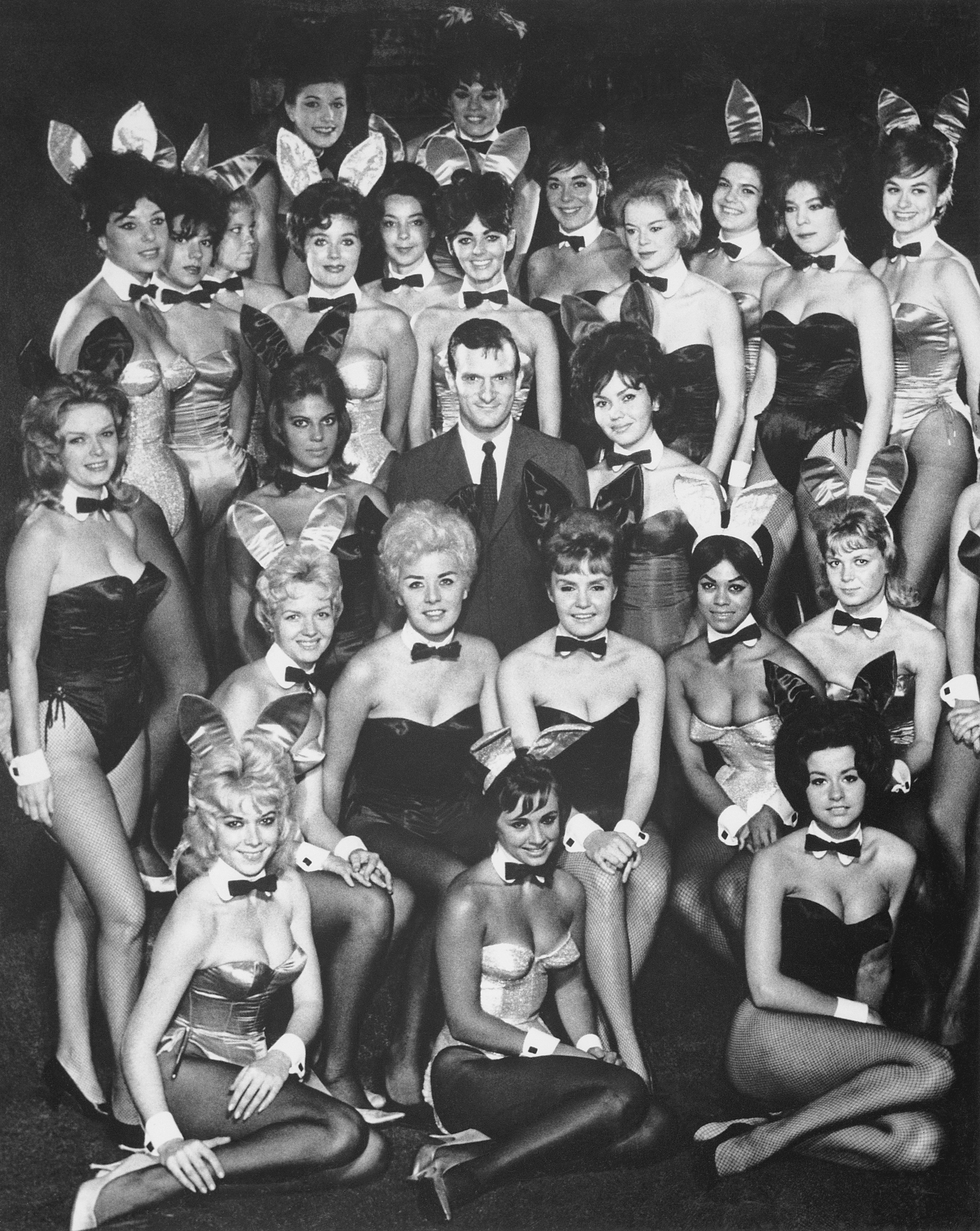

Almost as soon as I arrived in Manhattan to seek my fortune, I backed into a knuckle-bruising battle with Playboy's Hugh Hefner.

My new city-slick literary agent, Lois Wallace, had signed me because she liked my articles in a zippy new Yale monthly called The New Journal. So after Playboy editors approached Lois about a piece on something called the new feminism, she lipped a smoke ring into her telephone and asked me, "How'd you like to be the first woman to write for Playboy?"

The year was 1969. I thought Playboy defined cheesy, but I was too timid to say so. Furthermore, I was afraid to admit I'd never heard of any "new feminists." Lois, however sophisticated, was a shouter: "You're in New York, dammit, not in some ivory tower."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Jim Goode, Playboy's articles editor, contacted me that afternoon. Speaking more slowly than I thought a human could, he explained that Playboy wanted an objective account of the entire spectrum of the brand-new "women's lib" movement. "These women have important things to say, and I want our readers to hear them," he said. "Write anything you like, but don't pass judgment. Be fair."

I didn't dare tell him I knew nothing of these women. But Lois shouted again and I accepted the assignment. I began scouring underground newspapers like the East Village Other and Rat for people to interview, ultimately attending my first consciousness-raising meeting with seven Columbia grad students in a Salvation Army–arty apartment above an Upper West Side Chinese restaurant. I quickly learned consciousness-raising was based on a concept from the Chinese revolution called "speaking bitterness." For my subjects, it meant articulating the private indignities they suffered because they were women.

At meeting after meeting I heard a wide range of women speak passionately or woodenly about their "women's rage." They hurled questions: Why did men insist they were "helping" a woman do her job if they did housework? Should women compete for power outside the home like men? Would women ever be as free to enjoy sex as men?

Yet I wasn't ready to make the leap from anecdotes to political analysis. Of course I saw my husband as my superior intellectually and socially; that's largely why I'd been drawn to him. I hadn't consciously dared to resent this. I'd been given many votes of no confidence by men entrusted with my higher education. My philosophy professor had given me an A before he bought me a chocolate-chip ice cream cone and advised me to quit grad school and get married. Now, one short year later in New York, talking to crazed visionary feminists blew my mind.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of the 50-some women I interviewed, Gloria Steinem was the one I liked best. At this point she wasn't a feminist activist, but a respected journalist in miniskirts and suede who reported positively on the new movement. She was not a mad visionary, but utterly contained.

I was hypnotized by Gloria. She was as gorgeous as anybody I'd seen on the movie screen and was what I longed to be: a sophisticated New York woman. She exhaled dazzle. Gloria slept on a hip platform bed and used her bedroom as a home office. She stocked her refrigerator with only green bottles of Perrier water and a lime.

I watched a parade of men ring her doorbell proffering chocolates, flowers, and publishing offers. "I'll never get married," she told me. "Fifty percent of the women in this town are masochists — they're wives. Wives get no respect. Widows get respect."

After I sent my article to Playboy, Goode telephoned. "You've done a fair and objective piece. You followed instructions." All that remained was a routine clearance of the piece by A.C. Spectorsky, the associate publisher and editorial director.

I was still feeling victorious a few weeks later when I found myself in Chicago researching an article for Life magazine. I decided to give Goode a kind of well-I'm-in-town-so-I-thought-I'd-say-hello call. He invited me to lunch. At the Playboy offices, Goode became suddenly busy, but sent me to lunch with the magazine's lone woman editor, Julia Trelease. She turned out to have an amused perspective on our position: the rare woman writer being schlepped onto the sole woman editor.

Several female secretaries joined us. One mentioned that the joke going around the office before I'd arrived was that I would be instantly recognizable because I'd be wearing combat boots and battle fatigues. One secretary pursed her lips and told me that she didn't think my article would ever see print. When I nervously questioned her, she answered, "Oh, I just don't trust people around here when it comes to women."

I discovered these Playboy women knew much more about the new feminism than I'd expected. They'd read my article and liked it. I worried aloud about confronting Playboy on such a sensitive issue: Women displayed breasts in Playboy, not brains.

Afterward I chatted with Nat Lehrman, the associate publisher and self-described "sex editor." He joked about castrating women, nervously jingling coins in his pants pockets. My article had a couple of snags, he said. By building my story around three central figures — Betty Friedan, Robin Morgan, and Roxanne Dunbar — I'd been too sympathetic to "crazies" within the movement. Lehrman had penciled in a few suggestions, which he said pointed up the differences between "the radical crazies and the moderates." He apologetically read me his "minor" corrections. "It'll be a snap," he coaxed.

Boy, was I naïve. How could I have believed that Playboy would run a fair article about women's liberation? Hefner had admitted on The Dick Cavett Show, with a sincere furrow between his brows and a large suck on his pipe, that Playboy didn't try to present a three-dimensioned view of women in pictures and stories. Why? Well, because the magazine is written for men, not women.

Lehrman extended his "light edit" by solemnly citing chapter and verse of the Playboy "philosophy." He spoke of erotic stimuli and societal repression. I bent my head to the table to take notes, hiding behind my long hair. That night in my hotel room in the Playboy building I puked into a wastebasket. My husband was encouraging on the phone. "Keep taking notes, drink water," he said.

The next day, Hefner materialized and handed me a memo about my piece. He was the first man I'd ever spoken to with dyed hair. Hefner claimed he'd gotten late word that an objective article was in the works, and he was furious that such a piece could have been assigned behind his back.

The women's movement is rejecting the overall roles that men and women play in our society — the notion that there should be any differences between the sexes whatever other than the physiological ones. It is an extremely anti-sexual unnatural thing they are reaching for. It is now up to us to do a really expert, personal demolition job. Clearly if you analyze all of the most basic premises of the extreme new form of feminism, you will find them unalterably opposed to the romantic boy-girl society that PLAYBOY promotes.

Doing a rather neutral piece on the pros and cons of feminism strikes me as being rather pointless for PLAYBOY. What I'm interested in is the highly irrational, emotional, kookie trend that feminism has taken. These chicks are our natural enemy — and there is, incidentally, nothing that we can say in the pages of PLAYBOY that will convince them that we are not.

My stomach growled, but I was speechless.

I didn't get how right Hefner was. It took us decades, but it happened: Ordinary women helped destroy the Playboy way of life as a model of coolness for American men. At the age of 89, an apparently immortal Hefner has acquiesced: Playboy, which has featured nude women — famous and not — in its pages since its first issue in 1953, no longer publishes pictures of naked women.

But back then, Hefner's memo meant trouble for his Playboy editors and for me. "Sex expert" Lehrman ushered me into his office decorated by photos of women posed with nightclubby 1950s provocativeness. He played with the change in his pants pocket. I no longer felt shy. I was angry.

Lehrman waved "Hef's" memo, declaring that bigger changes were in order. And more upsetting, he decided to argue me into making those changes. Debate ensued; I politely refused to skew topic sentences and details against my article's subjects. We continued to argue. He kept saying, "I told them not to hire a writer with ideological hang-ups."

Lehrman asked me to spend another night in Chicago while he puzzled out a compromise. The next morning, he offered me a solution. I was to redo my article to remove every nuance of editorial sympathy with the feminists. It would be coldly descriptive. Then, a male author would write a separate article analyzing sex roles in this country, which would tout the Playboy line. Herbert Gold, Lionel Tiger, Philip Roth — these were a few of the names I heard discussed as potential masculine analysts.

I called my husband and told him that I was not going to be home that night. Back in my hotel room, I ordered a solitary dinner, took two Valium, and went to sleep.

The next morning I greeted Lehrman, who offered me an olive branch. He told me with a flashing glance that our argument had upset him so much that he'd had to take a sleeping pill to get to sleep. "Well," I smiled, prepared to accept the peace offer, "it took two tranquilizers to get me asleep." "Tsk, tsk," he wagged his finger at me. "No good, that lowers the sex urge."

I then argued about my article with a different editor. I asked if I could simply use the first person to speak as a woman. No, he said, and insisted I write solely about man-hating in the movement. At one point I asked for a guarantee that if I agreed to changes in the article Playboy would make no further edits. He said, "Not on such a sensitive issue."

During our discussion, several hip-looking Playboy people ducked into the office to tell me abruptly they were on my side. Male editors told me they were upset that Playboy's first serious article on the role of American women would emphasize the militant crazies of the women's liberation movement. One young woman said she'd been sad ever since she'd heard what was happening to my article, predicting trouble among Playboy's woman employees.

I didn't realize yet that the issue of Playboy's distortion of the women's rights battle — and the refusal to allow me my own voice in an article I'd been assigned to write and which had been accepted by the editors who assigned it — was much bigger than my personal defeat.

I withdrew my article. I soon learned Playboy had hired Morton Hunt to write a piece expressing Hefner's point of view.

Months later, I heard a TV news broadcaster announce, "Playboy employee quits over exploitation of women by Hefner." I wasn't sure I'd heard right, but sure enough, Shelly Schlicker, a Playboy secretary, had been caught late one night xeroxing Hefner's memo about my article. Playboy's piece on the new feminism had just appeared and Schlicker wanted to get Hefner's revealing memo to the press.

Her story was picked up by many underground newspapers and by Newsweek, which praised my courage. Hunt's article astonishingly concluded by relegating the women's movement to "the discard pile of history"; in response, Newsweek called it a "long, rambling, and rather dull article." (A year later, Newsweek hired me as their second woman writer ever.)

I laughed. Playboy's title for Hunt's piece ("Up Against the Wall, Male Chauvinist Pig!") was the kind of invective I was too "ladylike" to hurl at the magazine's editors. But I would have loved to have had the chutzpah to say, "Up against the centerfold, Male Chauvinist Pig."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in Jezebel.com. Reprinted with permission.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage