How a union raises your wage — even if you're not a member

Three cheers for labor!

Are labor unions a universal good?

Critics have long held the opposite, arguing that while unions line members' pockets, they leave non-unionized workers with lower wages and fewer job prospects. But supporters counter that when unions strike bargains for their members, even nonunion workers benefit.

New research unveiled Tuesday suggests the supporters have a point.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The study — released by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) — collected information on union strength as well as wages for non-unionized workers. The data ranges from 1979 to 2013, across four geographic regions and 18 industrial sectors.

The significance of that period is that unions got walloped during it. The portion of American male workers in a union fell from 34 percent to 10 percent. For female workers, unionization went from 16 percent to 6 percent. So if there's a link between union strength and wages for nonunion workers, picking through this time period is one possible way to find it.

Using statistical tools, the researchers found a pretty strong positive correlation: Where and when unions were strong, nonunion workers enjoyed higher wages.

But there's a lot that could be going on here. The effect of unions on wages could get tangled up with changing levels of demand for labor in different markets, the effects of technology, racial discrimination, and more. Statistical tools can also control for those various possibilities, but there's no way to disentangle it all perfectly. You might wind up undershooting the effects of unions themselves if you're too aggressive controlling for other factors.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

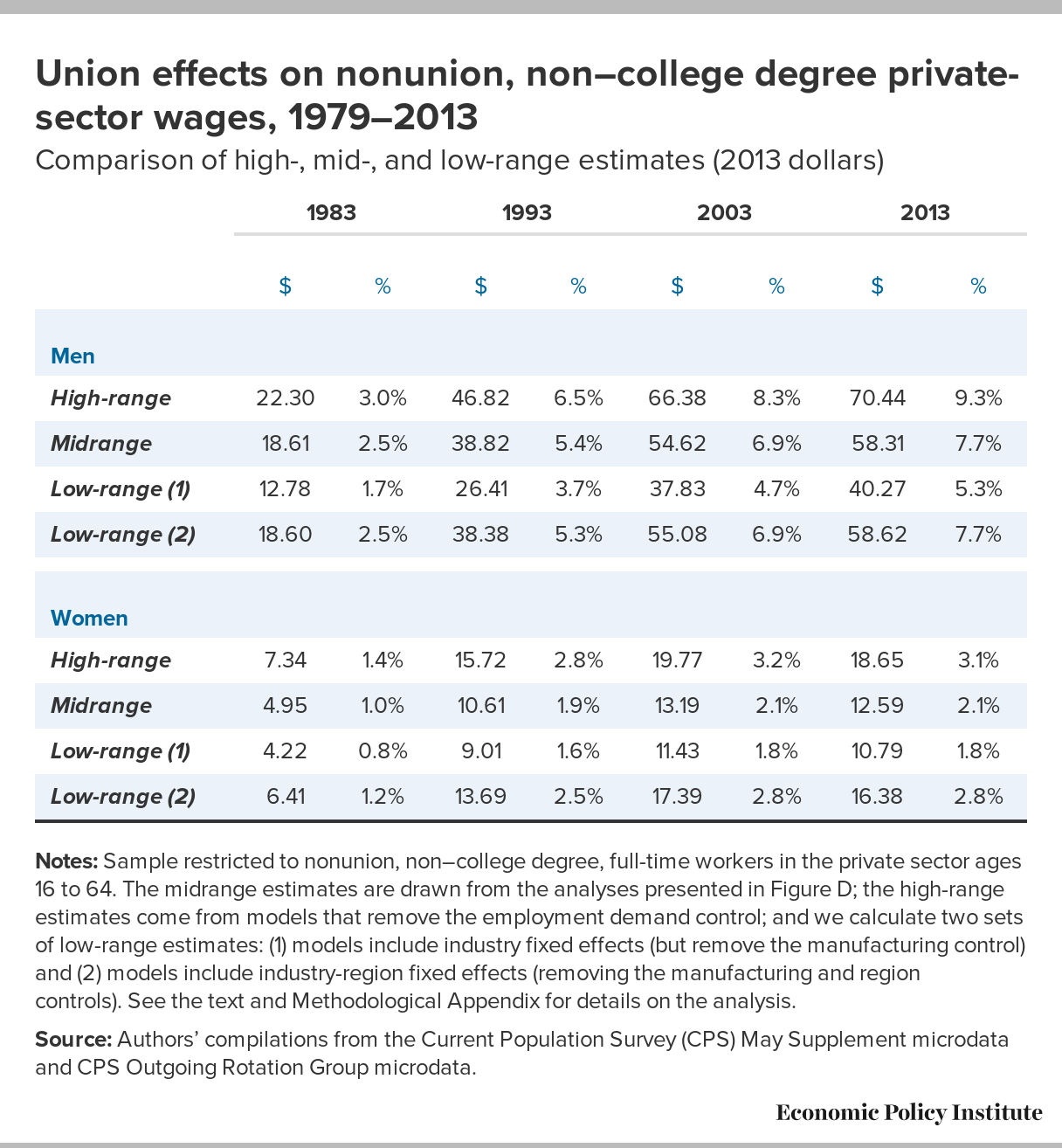

So the researchers produced a range of estimates of how much higher nonunion workers' wages would have been if union strength had stayed where it was in 1979. The "high-range" is less stringent about isolating the effects of unions on nonunion workers' wages. The two "low-range" estimates are variations on a more stringent approach. And the "mid-range" splits the difference.

Here's a table of the results, broken up for men and women, with snapshots in four different time periods:

If unions in 2013 were as strong as they were in 1979, the wages for male nonunion workers without a college degree would've been 7.7 percent higher, according to the mid-range estimate. That works out to $58.31 extra a week — or over $3,000 a year that workers who weren't in unions lost because unions eroded.

For nonunion female workers without a college degree, their wages would've been 2.1 percent higher in 2013, according to the mid-range. "Women were not as unionized as men in 1979," explained Jennifer Laird, a postdoctoral research scientist at Columbia University, and one of the study's co-authors, in a call with reporters. So nonunion women's wages were hit less hard by union's collapse.

This table concentrates on workers without a college degree because, even in 2013, Americans who have graduated college only made up about 31 percent of the populace. Back in 1979, they made up even less.

On top of that, when we worry about stagnating incomes in the last few decades — and all their baleful social and political results — it's primarily the incomes of non-college-educated men that we're talking about.

But even if you look at wages for nonunion male workers across all education levels, results are still dramatic: Wages for the entire group would be 5 percent higher in 2013 if unions hadn't collapsed. That's $52 extra week, or $2,704 a year. For all nonunion female workers, their wages would be 2 to 3 percent higher.

In sum, "union decline has cost nonunion workers billions in take home pay over the last few decades," said Jake Rosenfeld, an associate professor of sociology at Washington University and another co-author of the research.

Practically speaking, how could unions raise wages even for workers who don't join them?

The researchers pointed to several possible reasons: Most obviously, if employers are in an industry or region with lots of unionized workers, they may have to hike pay just to avoid losing employees to better pastures. Matching the unionized workplaces in pay might also be worth it for an employer just to avoid the logistical hassle of dealing with a union themselves.

But unions' effects on non-unionized workplaces could also be broader. Higher union pay might set cultural norms for how to treat workers. And unions have long provided the political and organizational oomph to fight for laws that benefit all workers, not just unionized ones. Rosenfeld noted that unions are currently helping to push for higher minimum wages and stronger overtime rules. "That's what unions do now," he said. "You can imagine their impact was even larger when organized labor was much stronger."

Indeed, Rosenfeld and Laird and their fellow researchers found that the strength of unions' effect on nonunion wages has decreased over time, suggesting the nonunion ripple effects of union efforts are bigger when union membership is higher.

But perhaps the most striking observation the researchers made is this: Previous research has teased out how damaging globalized trade has been to the wages of non-college-educated workers. But even globalization doesn't measure up to the loss of unions. "The erosion of unions on the wages of both union and nonunion workers is likely the largest single factor underlying wage stagnation and wage inequality," the study concluded.

That's something for all Americans, the vast majority of whom aren't unionized anymore, to think about.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of living

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of livingThe Explainer Telluride is the latest ski resort experiencing an instructor strike

-

‘Space is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement in Washington’

‘Space is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement in Washington’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?In the Spotlight John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy