The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Early in the pandemic, observers speculated about how the coronavirus would spur an outmigration from America's big cities. But a recent New York Times report on movement during the pandemic threw cold water on the idea that people are fleeing the horrors of urban areas for the comforts of rural life or the attractions of smaller, cheaper cities like Boise, Idaho. Instead, for the most part, places that gained or lost population in 2019 did so again in 2020. There was no mass exodus from the cities, and people who did leave mostly didn't go far.

This is not what was supposed to happen. City dwellers were meant to have some kind of epiphany a few weeks or months into their isolation: Why be trapped in an apartment or condo when I could quadruple my space and lower my cost of living by moving a few hours outside of the city? Maybe now is the perfect time to get away from the crime and the chaos and the inescapable reality of being surrounded by millions of my fellow citizens, and to buy an enormous house in a struggling small town. At least there I won't have to worry about some stranger in my building breathing the plague on me in the laundry room.

It is true that New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston lost more people in 2020 than they did in 2019. But the factors driving population loss in these cities have been a problem for years, most of all a lack of affordable housing in desirable neighborhoods, a particular challenge for families who need more space for their kids to bounce off of walls and fences. But even there, many of those who relocated during the pandemic did so on a temporary basis and plan to return when it's over. Temporary change-of-address requests with the post office were far higher than permanent ones.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Take Chicago, America's third-largest city, where I live. The city has been hit hard by COVID, and features large expanses of the kinds of high-rise condo buildings that turned into towers of terror during the pandemic. There have also been multiple, unpredictable disruptions of daily life stemming from racial justice protests and unrest. One friend was basically imprisoned with his family in their downtown condo for days at a time over the summer. And this was already a place whose brutal, unforgiving winters challenged your psychological fortitude between December and April and that has been gradually losing population to the Sun Belt for decades.

Yet despite these very real challenges, the city's real estate market is booming, with sales of condos up 22.7 percent in October 2020 from a year earlier. And single-family homes in the city are getting snapped up so quickly that there are very few listings available at all. Rent prices, which fell sharply in the early months of the crisis, are rising again. Fears that pandemic-driven revenue loss would crush the city's higher education institutions also proved overblown.

There are certainly very real worries about how the commercial real estate market will survive in a post-pandemic world where remote working is more common, but neither companies nor individuals are currently acting like they will no longer be tethered to the city's commercial core or that they no longer plan to have physical offices. Only about a third of people working remotely would like to do it forever, absent the risk of COVID-19. Once the shock of the pandemic wears off, it is more likely that the big change will be the desire to work remotely on occasion, rather than commuting five days a week.

In the end, the population of the Chicago metro area (what is adorably called "Chicagoland" here) increased in 2020 while the city itself experienced another in a long line of marginal decreases, hardly a sign that legions of young folks in the Windy City decamped for Boise or the rural hinterlands and more proof that pre-2020 trends were the most important factor in understanding what happened to cities during the pandemic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As the merciful end to the pandemic in the U.S. comes into view, Chicago is mostly the same place it was before. People who, in 2019, wanted easy access to every cuisine on the face of the Earth, a vibrant arts scene, major league sports, and one of the country's most robust public transit systems are likely to still want it in 2021, and they won't find all of those things at the same scale in Nashville or Raleigh. And they won't have any of them in the countryside. On the other hand, for city-dwellers who yearned for huge yards and lower housing prices in 2019 — younger families in particular — the pandemic probably just accelerated a migration to the suburbs that was going to happen sooner or later anyway.

Predictions that the pandemic would obliterate small businesses and hollow out neighborhoods have also been proven a bit overblown, at least where I am. There have certainly been closures, and many will be permanent. But in my Chicago neighborhood full of small, family-run restaurants and shops, nearly all businesses and restaurants are still open thanks to support from the COVID relief bills that made it through Congress. The barbershop I went to in the Before Times is still there. So is the tiny little pet store. The brunch spots are thriving. The most beloved neighborhood bar is open.

This is not the product of living in some bougie remote-worker oasis. My neighborhood of West Ridge is the most diverse in the city, with an unusually broad mix of income levels. And in any case, job losses and business closures are not any worse here than they are in rural areas or even in some of the buzzy cities that were growing before the pandemic, like Austin, Texas. As of February 2021, the employment rate was down more than 36 percent in Boise, year over year, as compared to just 7.6 percent in Chicago. In many parts of rural Pennsylvania, job losses have been worse than they have been in Philadelphia. And so on.

The analytical error in predicting widespread flight from cities was to confuse those who thought it might be best to beat tracks for their parents' houses in the suburbs until the pandemic ended with people for whom the coronavirus and its attendant inconveniences were the breaking point with city living altogether. There were a lot more of the former than the latter. And the whole "best places to live" genre wildly overestimates the number of people who are willing to pick up and move away from their families for sunnier climes in the first place.

The onset of the pandemic produced a lot of breathless future-telling based on little more than the author's ideological desires about the world as they would like it to be. A lot of people who think cities are terrifying, dangerous, and overwhelming only saw the challenges of the pandemic and not the enduring strengths and attractions of big cities, in the same way that many progressives thought it was self-evident that the pandemic would lay bare the inadequacy of the U.S. social support system and lead to a Democratic wave in November.

Our cities have their problems, but they are mostly the same as they were in 2019 — not enough housing, a shrinking middle class, widening inequality, rampant gun violence, police forces who see us as subjects rather than citizens, and too many white Democrats who would rather perform the easy rituals of racial justice rather than make the hard sacrifices necessary to transform their cities into more equitable and just places to live. But while it may disappoint the urbanophobes among us, and while it has not been easy surviving this thing in the big city, most of us have chosen to stay and fight, and we'll be here long after this cursed virus gloms onto its last victim.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy

-

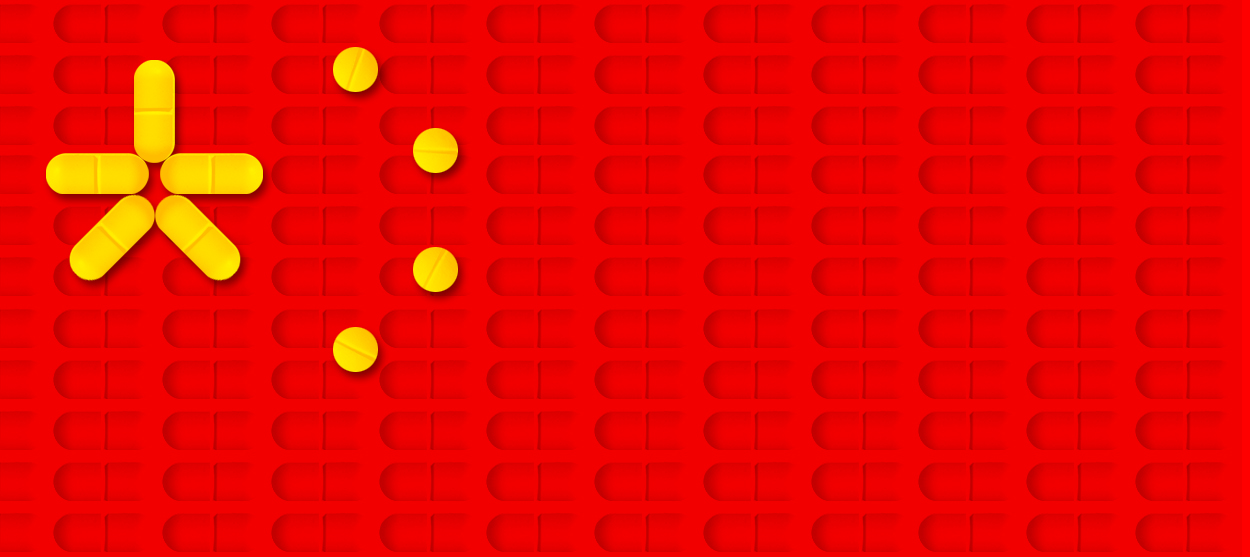

America could run low on medicine at the worst possible time

America could run low on medicine at the worst possible timeThe Explainer Another coronavirus lesson: Don't offshore all your basic drug manufacturing