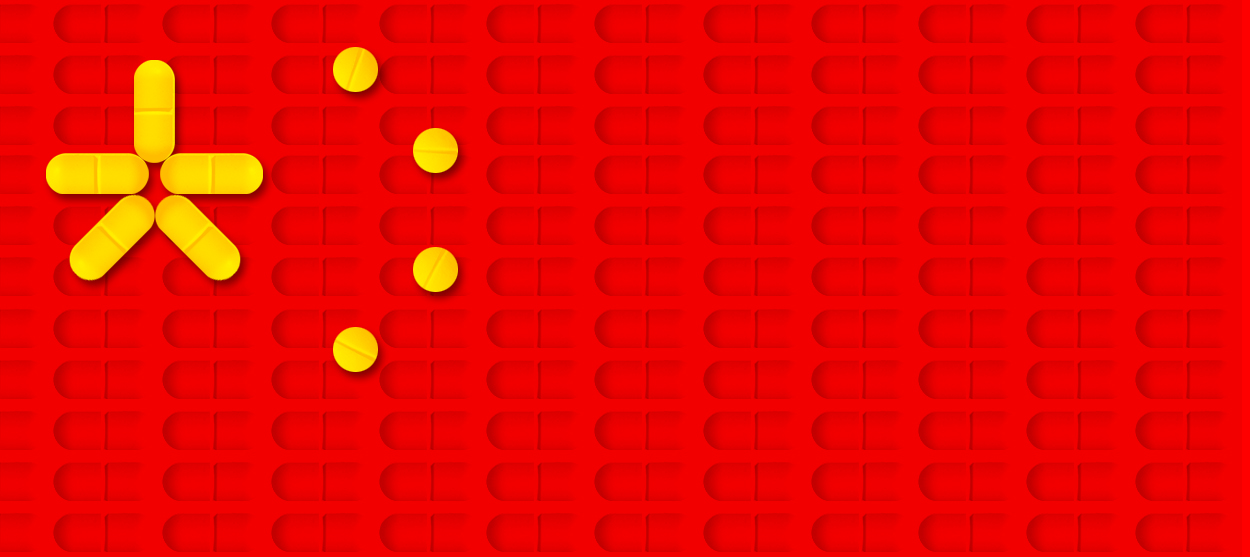

America could run low on medicine at the worst possible time

Another coronavirus lesson: Don't offshore all your basic drug manufacturing

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By now, it seems pretty clear that China was caught flat-footed by COVID-19, known colloquially as the coronavirus, with potentially dire consequences for the country and its economy, not mention the rest of the world. But there's an additional unpleasant irony to that already grim news: Thanks to the way America's pharmaceutical industry has rearranged its global supply chains, a medical crisis in China could possibly throttle the supply of drugs Americans need to fight a medical crisis here.

Hard data on the situation is hard to come by, both because Chinese data sources are not exactly trustworthy and because these companies are cagey about sharing what they consider to be proprietary information. But here's what we know: Anywhere from 80 percent to 88 percent of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) — the basic building blocks used to manufacture drugs in the United States — come in from abroad. Roughly 13 percent or 14 percent of all the APIs used to manufacture U.S. drugs come from China. And 14 percent is hardly a tiny amount. More to the point, even this number undersells the degree of our dependence on China.

There are 370 drugs sold here in America and considered "essential" by the World Health Organization that are at least partially dependent on APIs from China. We rely on the country for components to drugs that treat everything from epilepsy to depression to Alzheimers. Three of those drugs — “Capreomycin and streptomycin, both used to treat mycobacterium tuberculosis; sulfadiazine, used to treat chancroid, a sexually transmitted disease; and trachoma, a bacterial infection of the eye,” according to CBS — use components that only come from China. The United States also keeps a strategic national stockpile of critical drugs, and 85 percent of those use at least some API that China manufactures. Beyond drugs, Chinese manufacturers are major producers of other medical devices, like catheters, MRI machines, devices for monitoring blood oxygen levels, dental implants, and more.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The problem is that the way to prevent the spread of a disease like COVID-19 is to quarantine infected populations, shutdown or tightly regulate travel, and keep people in their homes and away from congregating in groups — all of which the Chinese government and authorities have done with gusto. But, by definition, this means shutting down places of work and factories and other hubs of industry, including many of China's 4,300 pharmaceutical and API manufacturers. According to reports from within the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the agency is keeping its eye on a list of 150 drugs — including both generics and unique patented pharmaceuticals — that are at risk of shortages if China's manufacturing shutdown continues. Critical antibiotics like penicillin, amoxicillin, and doxycycline — which get 90 percent of the APIs from China — are also among those at special risk.

Thanks to the coronavirus outbreak, demand within China is also rising for certain drugs, particularly anesthetics and pain relievers. Even if manufacturers can keep cranking those drugs out, there could still be shortages anyway, simply because China has to stockpile more of them for its own needs rather than export them to everyone else. Finally, even if drugs or their components are produced in China, the manufacturing sites still have to be inspected by the FDA to clear them for sale in the United States. And the shutdown of Chinese society to contain COVID-19 risks curtailing and delaying those inspections as well, which would then cascade into delayed drug shipments.

"We are keenly aware that the outbreak will likely impact the medical product supply chain," the FDA said in a statement.

"If China shut the door on exports of medicines and their key ingredients and raw material, U.S. hospitals and military hospitals and clinics would cease to function within months, if not days," Rosemary Gibson, the author of China Rx, which covers how a lot of America and the world's pharmaceutical manufacturing now depends on China, told NBC back in September.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Our biggest vulnerability is overdependence and single source of supply," Mike Wessel, a member of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, explained late last year. "For critical products like antibiotics as well as life-sustaining drugs like blood pressure medicine, China, directly or indirectly, is the major or potentially sole supplier of those products to the U.S."

In fact, high-profile lawmakers on both sides of the aisle were worrying about this problem late last year before the coronavirus even hit the news. In that case, the issue was national security: Government officials were concerned China might retaliate in its ongoing trade war with the Trump administration by choking off America's drug supply. There were also worries that, FDA inspections or no, China's standards are lax and could lead to dangerous or contaminated drugs entering the United States. In fact, in the last few years, America and Europe have seen several recalls of Chinese-manufactured vaccines and other drugs for exactly this reason.

At the same time, China is as dependent on these trade relationships as the U.S. is. Thus, it's been trying to improve its inspection processes. Any trade war effort to constrict America's drug supply would also invite retaliation, since the U.S. exports a lot of end-product drugs (built from the APIs) back to China.

But in those cases, we're relying on China's national self-interest to prevent it from exploiting a vulnerability. What's disturbing about the COVID-19 outbreak is that it obeys no such logic. Another example of a natural disaster shutting down these supply chains actually came in 2017, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico: One plant on the island was responsible for half the small saline bags used by American hospitals, and when the supplier had no backup, hospitals across the country were suddenly short.

The good news is that, so far, drug shortages remain a potentiality rather than a reality. Drugmakers of course prepare for supply chain disruptions, and to an extent, they can turn to alternative suppliers around the world. Pharmaceutical companies are required to inform the FDA of any supply disruptions, and the agency is actively in contact with them for news. According to reports, no one has informed the FDA of a shortage yet. Major suppliers like Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Roche, and Pfizer all told CBS they have alternative suppliers on hand, or other contingencies to address a shortage.

At this point, the most disturbing thing is the simple lack of information. We're relying on China and private companies to provide honest assessments, and to have appropriate backups — nevermind that the mad rush for cost-cutting is what led to the massive offshoring of these supply chains in the first place. "One of the big unknowns is how many products are sole-sourced — in which literally only one place in the world makes that raw material," Erin Fox, a University of Utah Health expert on drug shortages, told Wired. "We don't have good information on that at all." There's also the fact that it takes a while for inventories to turn over, so there will likely be a lag between the shutdown of API production in China and any shortage America may experience.

If nothing else, the episode highlights how risky it is for big corporations to concentrate the global supply chains for critical needs in one place, based on profit calculations rather than concerns about redundancy or national security. "All it takes is one plant to shut down to cause a global shortage. That's because there's such concentration of global production in China," Gibson told Wired.

At the very least, that seems imprudent.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.