America never recovered from 9/11

The terrorists didn't win 15 years ago. But that doesn't mean our scars have healed.

In the days and months after Sept. 11, 2001, there was a maxim — at first serious, then darkly comic — that if you didn't go on living your life (i.e. working, eating, loving, shopping), the terrorists had won. The idea is laudable — terrorism only works if the targeted population is terrorized — and al Qaeda did not win. But America lost something just the same. Some wounds take time to fully heal. This one still hasn't.

After 15 years, America seems to have moved on in many ways. There is a new World Trade Center skyscraper in Lower Manhattan near where the Twin Towers once stood, and a museum and memorial are situated on site. The Pentagon is repaired. There will be people voting this year who were toddlers in 2001.

But you don't have to look far to see the ghosts of 9/11.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

U.S. troops are still in Afghanistan, the country America invaded less than a month after the terrorist attacks to deny al Qaeda its safe haven. President Obama is fighting the Islamic State — a group that formed from the ashes of an al Qaeda offshoot in Iraq — using the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) passed by Congress on Sept. 14, 2001. U.S. troops are also still in Iraq, the country President George W. Bush had the U.S. invade after 9/11. Hillary Clinton's vote as a senator to authorize Bush's invasion was a key reason she was not the Democratic presidential nominee in 2008.

The ghosts of 9/11 linger at the airport, where you pass through security procedures enacted in response to the attacks, overseen by employees of an agency, the Transportation Security Administration, that was created after the attacks along with its parent organization, the Department of Homeland Security.

Without 9/11, you probably wouldn't turn on your TV today and see Rudy Giuliani, a top Donald Trump adviser who, in August 2001, was an unpopular lame-duck New York City mayor before he rallied a city and a nation after the attacks. You probably also wouldn't hear about Michael Bloomberg, the gun-control-promoting mayor who succeeded Giuliani. Or Edward Snowden, the National Security Agency contractor who exposed the surveillance apparatus that was enacted in the wake of 9/11.

On a more somber level, people are still dying from cancer and other ailments tied to the heroic search for survivors and human remains at Ground Zero. There were 2,996 people killed in the attack itself, including 411 firefighters and police officers, but at least 653 rescue workers have also died since, Newsweek reports, many or most of them sickened by the "massive plume of carcinogens" released with the dust and smoke from the crumbling towers that transformed lower Manhattan into "a cesspool of cancer and deadly disease."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In all, as many as 400,000 people have been directly adversely affected by 9/11, including disease and mental illness, Newsweek estimates, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The psychological afflictions include post-traumatic stress, addiction, behavioral issues, and anxiety. The number of people still hurting surely exceeds that half-million estimate.

I'm lucky — nobody I know personally died on 9/11. But like everyone in New York at the time, I felt the losses. I had been working in the skyscraper across the street from the World Trade Center towers, and I was on my way to work when they fell, much closer than I should have been. I breathed in some of that dust, which looked like snow falling on that sunny September morning. I walked by the heels and ties and other objects discarded by workers as they walked to safety across the Brooklyn Bridge.

The planes on 9/11 crashed in New York, northern Virginia, and Pennsylvania, but it was an attack on the United States. The U.S. had won the Cold War, invented the internet, and was free and prosperous. Then suddenly we were fighting an endless war against an asymmetric-warfare tactic. Yes, tens of thousands of American service members died in Cold War proxy battles, but 19 hijackers had managed to do something Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany had not: Attack U.S. soil. Americans saw the image of the towers falling over and over again on TV. Fortress America had been breached.

Today, the most insidious residue from 9/11 is probably fear.

I'm not sure it has to be this way. After 9/11, New York City felt like a close-knit community. There was a sad beauty in the solidarity, the common loss, the communal realization of what was important in life. This year, The Associated Press captured some of that baffled nostalgia for unity lost from people who suffered much more than I did from the attacks.

America also seemed pretty united. There was a run on American flags, an abundance of donated blood. There was an ugly, violent undercurrent of Islamophobia, but there were also moments of catharsis. Ten days after the attacks, Bruce Springsteen kicked off the first of three major televised post-9/11 concerts, debuting a song he'd originally written for Asbury Park, "My City of Ruins." It became the anchor for his 9/11 album The Rising — inspired, Springsteen says, by a drive he took to the Jersey Shore soon after the terrorist attacks where, as he was driving off, a fan yelled from his own car, "We need you now."

Maybe that moment of togetherness, of promise, was never going to be more than a temporary calm amid turbulent partisan waters. Or maybe, through that togetherness, America could have collectively dealt with its grief and loss. What we did instead was invade Iraq, a betrayal of trust and pain that seems to have shut the book on that too-brief moment of possible recovery.

So here we are, 15 years after 9/11. Americans have a reputation for trying to present optimism and outward prosperity, putting our best foot forward. And outwardly, America is back, or at least on the mend — low unemployment, high stock market, wages that are finally creeping upward, a popular president, dropping violent crime rates. Yes, we've gone on living our lives. But a sizable chunk of the country is in a sour mood. Our politics are unusually disheartening. We're staring down generational conflicts we've long swept under the rug. Public discourse seems to be dominated by coarse trolls. There's still a hole in the American heart.

Or at least there's still a hole in mine.

As I prepare for my annual quiet ceremony of gratitude for being alive, of mourning for those who aren't, I can no longer remember the horrible smell that permeated New York City for those 90 awful days when the crumbled towers burned. My memories of the day itself are slowly fading into time. But I think the body remembers. America remembers. I think I lost something that day, and I don't believe I am alone.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Breaking news: the rise of ‘smash hit’ rage rooms

Breaking news: the rise of ‘smash hit’ rage roomsUnder the Radar Paying to vent your anger on furniture is all the rage but experts are sceptical

-

Did markets’ ‘Sell America’ trade force Trump to TACO on Greenland?

Did markets’ ‘Sell America’ trade force Trump to TACO on Greenland?Today’s Big Question Investors navigate a suddenly uncertain global economy

-

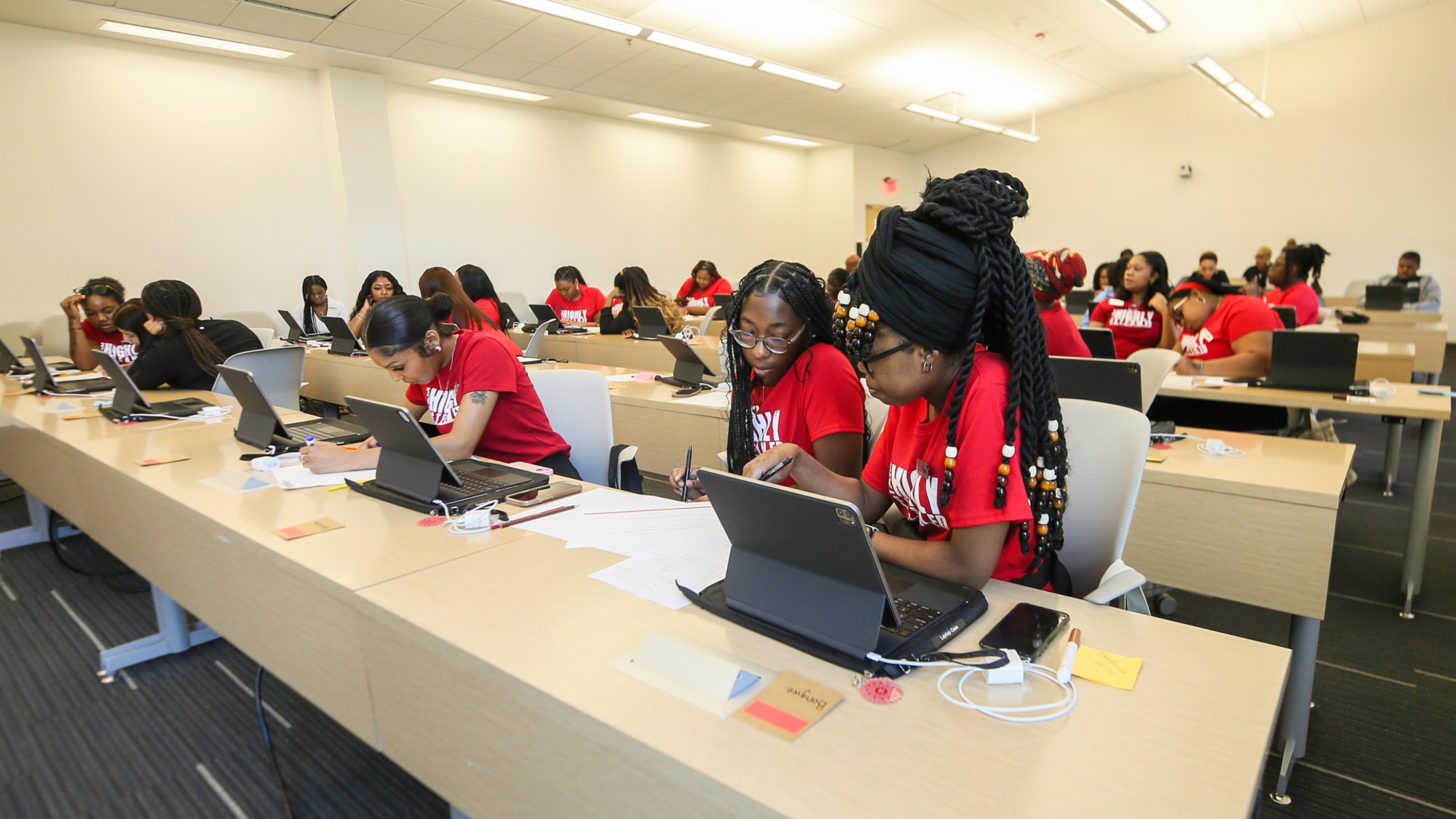

‘We know how to make our educational system world-class again’

‘We know how to make our educational system world-class again’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

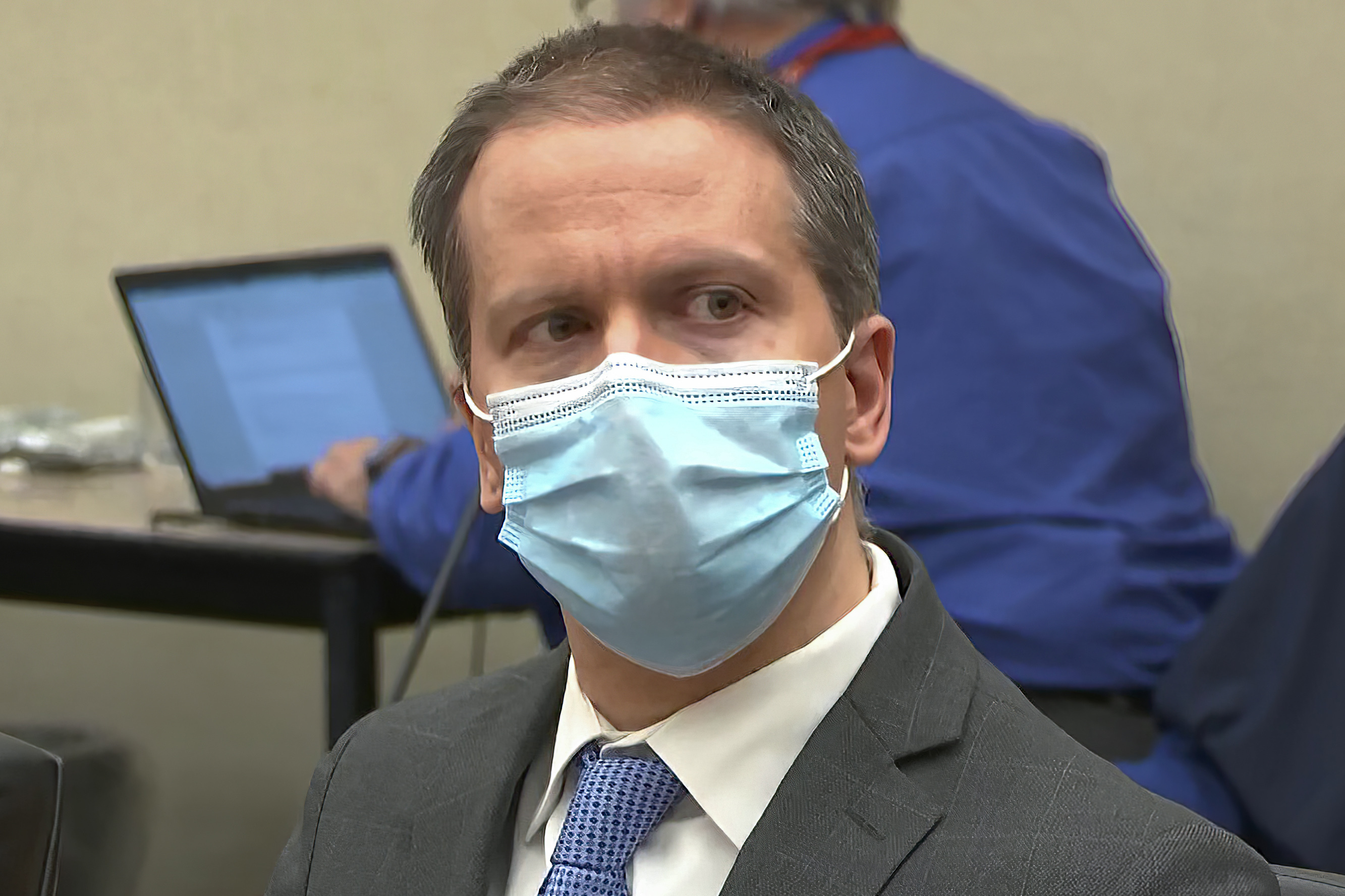

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read