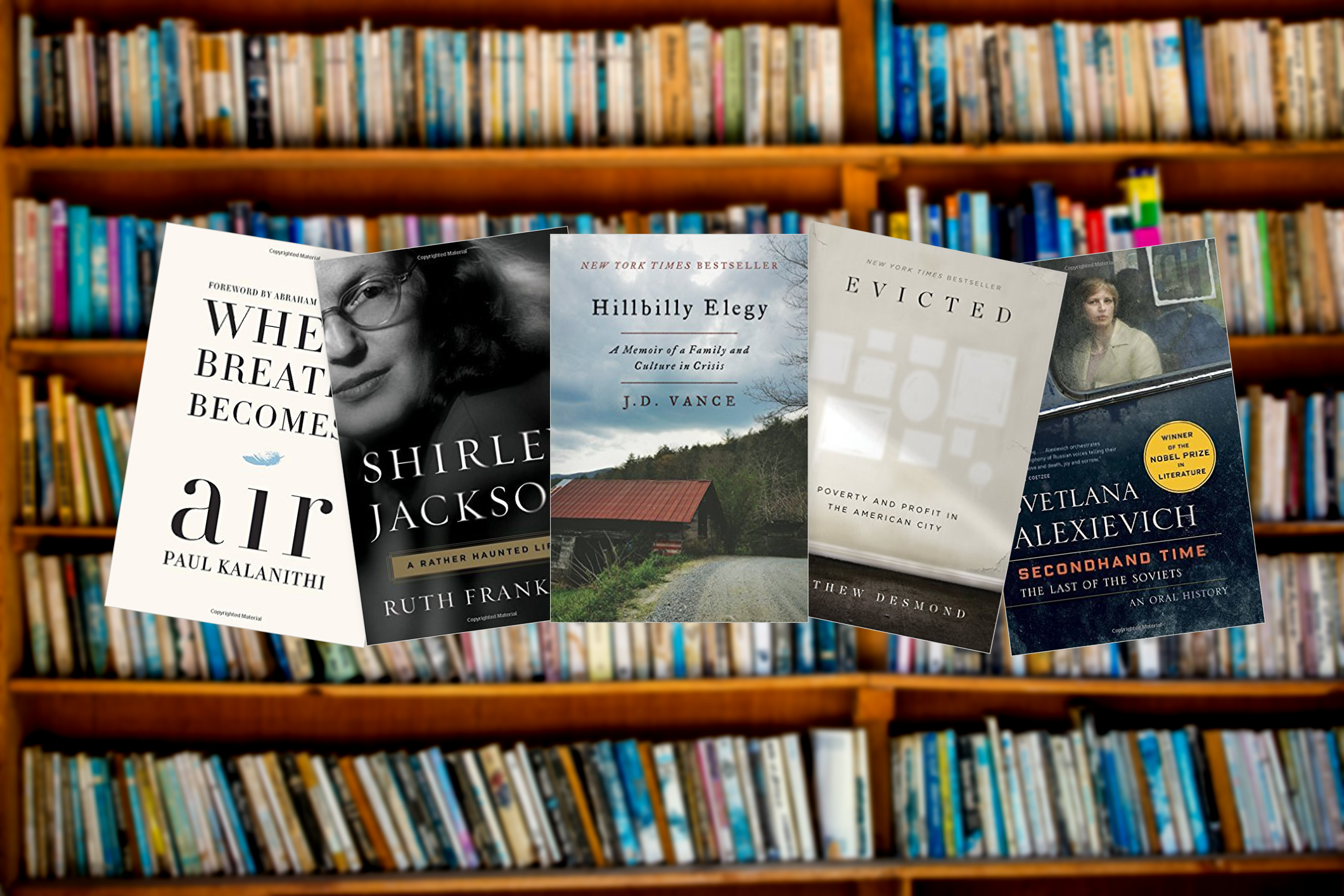

The 5 best nonfiction books of 2016

From Evicted to Hillbilly Elegy, here are the nonfiction titles critics loved this year

1. Evicted by Matthew Desmond (Crown, $28)

"The struggle to pay the rent may sound like a problem the poor have always faced. It's not," said Jason DeParle at The New York Review of Books. Matthew Desmond's "spellbinding" book pulls readers deep into lives that have been destroyed by the rising costs of even substandard shelter and by landlords who depend on often capricious evictions to turn a profit in the poorest neighborhoods. Desmond, a Harvard sociologist, gathered solid statistics to build his analysis, but it's his ground-level reporting in Milwaukee's rougher districts that lends his message such force. Greedy slumlords and troublesome tenants alike come alive as singular characters, and Evicted builds to become "a stirring reminder that the U.S. accepts as ordinary a depth of poverty that is extraordinary and cruel." Desmond, said Carlos Lozada at The Washington Post, "has made it impossible to ever again consider poverty in America without tackling the central role of housing." Buy it at Amazon.

A dissent: Desmond shows that government programs haven't remedied the problems he identifies — "then he proposes more government programs," said Charles Sykes at Commentary.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

2. Secondhand Time by Svetlana Alexievich (Random House, $30)

Not in decades has there been a work of Russian literature "as great and personal and troubling" as this 500-page oral history, said Bob Blaisdell at the Christian Science Monitor. Svetlana Alexievich won a 2015 Nobel Prize for producing books like this, books that create sweeping narratives by blending together the voices of ordinary people. Here, the Belarusian author takes as her subject the experience of living in the various states of the former Soviet Union both before and after the superpower's collapse. The stories the book shares were derived from hundreds of kitchen-table conversations recorded between 1991 and 2012, and many of those personal stories "clouded my eyes with tears." Soviet rule was brutal, but so too was the upheaval unleashed by its fall, said Thomas Dylan Eaton at Bookforum. Suicides and ethnic violence spiked, and even intellectuals who had cheered on perestroika were left destitute when the Russian economy cratered in the 1990s. Some of Alexievich's subjects mourn the authoritarian state they grew up in, but the catalog of human suffering she has assembled "rebuffs any notion of a grand Soviet legacy." Buy it at Amazon.

A dissent: Some of the stories told, though engrossing in substance, "can also be baggy and repetitive," said Dwight Garner at The New York Times.

3. Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance (Harper, $28)

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

J.D. Vance has excellent timing, said Geoffrey Norman at The Weekly Standard. In a campaign year defined by white working-class discontent, his beautifully written memoir delivered an "achingly felt" portrait of a dying Ohio steel town and its Appalachian culture. Vance's family springs from that "hillbilly" milieu, and the life his drug-addicted mother showed him proves "so full of pointless violence and self-inflicted wounds that if he were any less skillful in rendering it, readers would be tempted to give up." Vance acknowledges that the region has been hard hit by the loss of manufacturing, but blames his fellow hillbillies for the rut they're in, said Ronald Bailey at Reason. The author escaped, via the Marines, college, and Yale Law School, and urges others to follow. Still, he "fiercely identifies with and loves his people," and his story "makes compellingly personal" the news stories we hear about small-town America's social and economic struggles. Buy it at Amazon.

A dissent: Don't fall for Vance's victim blaming, said Sarah Jones at The New Republic. "Bootstraps are for people with boots."

4. Shirley Jackson by Ruth Franklin (Liveright, $35)

This "brilliant and heartbreaking" biography introduces a Shirley Jackson readers never knew, said Katherine Powers at the Chicago Tribune. Jackson, a celebrated writer of dark stories like "The Lottery" but also of cheery slice-of-life magazine essays, was long presumed to have had a morbid imagination but a relatively sunny mid-century American life. That myth has been "conclusively exploded" by critic Ruth Franklin, who reveals that Jackson escaped the relentless criticisms of her socialite mother only to marry a flagrantly unfaithful husband who took similar pleasure in belittling her. "Intentionally or not," Jackson channeled her frustrations into her writing, said Nina MacLaughlin at The Boston Globe. But she also became a heavy smoker, a drinker, and a pill popper, and Franklin proves herself "a skilled builder of tension" as we sense Jackson nearing her breaking point. The doyenne of suburban dread died at 48 of a heart attack, in 1965, and this "taut, insightful" account of her life "speaks to what it means to be a woman even now." Buy it at Amazon.

A dissent: Franklin unfairly demonizes Jackson's husband — a fellow writer who boosted his wife's career, said Blake Bailey at The Wall Street Journal.

5. When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi (Random House, $25)

Paul Kalanithi's "exquisitely moving" memoir "begins with a wallop," said Sandra Martin at The Globe and Mail. Reading his own CT scans in 2013, the 36-year-old neurosurgical resident learns that he has stage 4 lung cancer. The disease will kill him, readers already know, but he used the time he had left to write eloquently about facing his own decline and death. The challenge forced him, for starters, to figure out what really mattered to him as a husband, as a doctor, and as a human being. Kalanithi "grows his soul as his body wastes away," said Andrew Solomon at The New York Times. A man who earned master's degrees in literature and philosophy before taking up medicine, he lets us watch his turn to religion, and the decision he and his wife made, after much debate, to have their first child. The couple's daughter was born eight months before her father's death, in 2015, by which time Kalanithi had concluded that death requires a psychic and spiritual reckoning that science could not help him with. Kalanithi begins the book as a doctor, but "in these pages, he becomes a humanist." Buy it at Amazon.

A dissent: With some medical terms, "a word or two of explanation" would have been nice, said Louise Jury in The Independent.

-

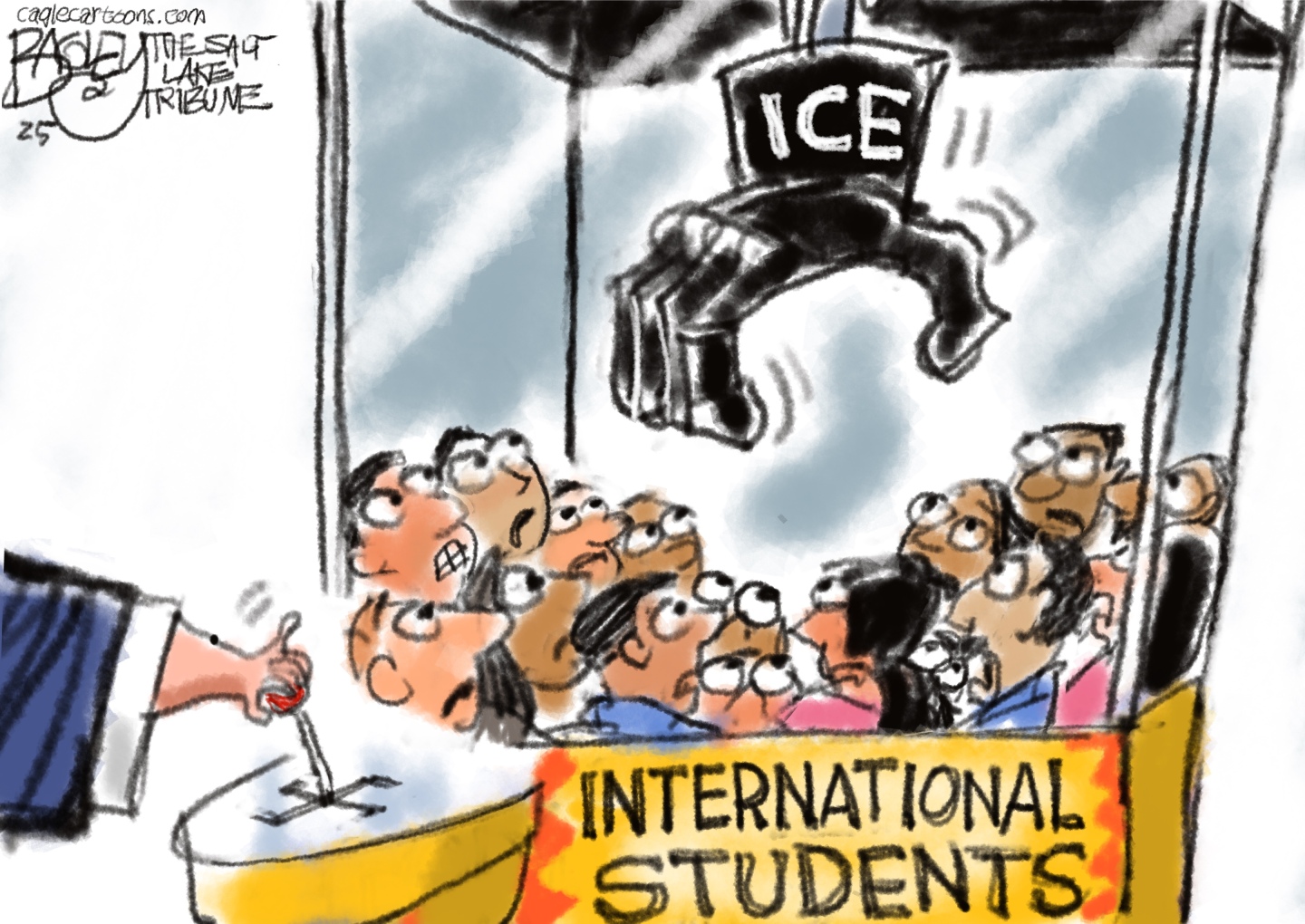

5 heavy-handed cartoons about ICE and deportation

5 heavy-handed cartoons about ICE and deportationCartoons Artists take on international students, the Supreme Court, and more

By The Week US

-

Exploring the three great gardens of Japan

Exploring the three great gardens of JapanThe Week Recommends Beautiful gardens are 'the stuff of Japanese landscape legends'

By The Week UK

-

Is Prince Harry owed protection?

Is Prince Harry owed protection?Talking Point The Duke of Sussex claims he has been singled out for 'unjustified and inferior treatment' over decision to withdraw round-the-clock security

By The Week UK