How ESPN went from powerhouse to bloodbath

The sad downfall of the Worldwide Leader in Sports

There was a bloodbath at ESPN on Wednesday.

A dramatic round of layoffs had long been expected at the Worldwide Leader in Sports, but the numbers turned out much bigger than predicted: Roughly 100 on-air reporters and personalities were let go, plus some additional behind-the-camera crew members. By Wednesday afternoon, people like Ed Werder and Scott Burnside — who'd worked at ESPN for 17 and 13 years, respectively — had announced on Twitter that they were toast.

The network, which employs about 8,000 people around the world, actually let a whopping 300 go in October 2015. But this week was unusual for the deep cuts to on-air talent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The bloodbath was the result of several colliding forces.

First off, ESPN's personnel costs are unusually expensive. Shows like SportsCenter, for instance, feature a raft of well-paid anchors. Stars at the network often earn anywhere from $1.5 million to $3 million. Hundreds of reporters and analysts get paid handsomely to gab on ESPN. All that hot air costs a lot of dough.

The next problem was falling revenue, thanks to a collapse in subscribers.

After peaking around 100 million in 2011, ESPN subscribers fell to 88 million in the most recent quarter, largely because of cord-cutting, or when customers abandon paid cable and TV packages for viewing options on the internet. Each subscriber pays as much as $7.21 per month — it's a basically invisible charge baked into your cable TV bill — which means the overall decline adds up to something like a $900 million drop in annual revenue for Disney, ESPN's parent company.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"ESPN seems to be bleeding money because of cord-cutting, so my salary was unattractive to them," Adam Rubin, who used to cover the New York Mets for ESPN, explained to The 30. "And the new MLB editor at ESPN wants to get away from 'thorough' beat coverage — that's the precise word she used — and I suppose I was the sacrificial lamb to hammer home that point."

And then there's the third force driving ESPN's troubles: the rising costs of broadcasting sporting events.

Any company that broadcasts a game for the NFL, NBA, MLB, or any other league has to pay a massive fee to do so. And those fees are ballooning: Collectively, television, radio, and internet companies paid $10.8 billion for broadcasting rights in 2011 and over $15 billion in 2015. Those costs are projected to top $21 billion in 2020.

The NFL takes in about $7.5 billion each year from charging fees to media companies. Recently, ESPN paid $2.66 billion to secure an NBA broadcasting package through the 2024-25 season.

To get a sense of scale, the very first national TV sports contract, inked between ABC and the American Football League in 1960, was a piddly $8.5 million over five years.

Companies like ESPN have to pass some portion of those costs onto their customers to stay financially viable. Since 2007, the monthly fee ESPN subscribers pay has jumped 120 percent. Needless to say, as that price tag rises, the constantly improving (and often free!) options for viewing sports on the internet become more and more attractive to people.

As for why the leagues are hiking their fees, the simplest answer might be because they can. While the individual teams ostensibly "compete" with one another, the leagues operate as something akin to a trust or monopoly, controlling the number of teams and the supply of sports entertainment. And while different teams used to do their own individual deals, the leagues long ago figured out the advantages of offering broadcast rights as a unit.

There's obviously some upper limit to how much the leagues can score before they drive away too many customers. But we don't seem to have hit it yet. People love sports. And there's only so many businesses that can offer pro sports to consumers. The NFL doesn't exactly have a lot of competition.

There's one other possible factor in ESPN's troubles worth mentioning: the general turn in sports reporting to a far more outspoken social liberalism. Setting aside the moral merits, it's certainly true that plenty of sports viewers don't share those liberal politics. That may have produced an extra shove for some customers: "When people begin realizing they can live without your business model, you can't give them more reasons to object to paying for it," as conservative columnist Steve Deace put it.

At the same time, parsing the degree of ESPN's liberalism, or how much it irked some portion of its viewership, is an impossibly subjective question to answer.

So in the end, like so many media companies, ESPN is trying to adapt to this digital age. The network is trying to increase its digital offerings, and Disney bought a $1 billion stake last year in a new streaming service launched by Major League Baseball.

"Dynamic change demands an increased focus on versatility and value," ESPN's president, John Skipper, told employees Wednesday. "As a result, we have been engaged in the challenging process of determining the talent — anchors, analysts, reporters, writers, and those who handle play-by-play — necessary to meet those demands."

That's dry language, but in practice it amounts to nudging out a lot of people with contracts about to expire, by telling them they could only stay on with a big pay cut. In some cases, ESPN offered people with years left to go just 50 percent of the money remaining to them — or they could finish out their contracts while effectively being benched.

For the moment, ESPN's costs will be slimmer and its books will be easier to balance. But neither the internet nor the heavy hand of the sports leagues are going anywhere. So the squeeze will continue.

In the end, all ESPN may buy with this bloodletting is time.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

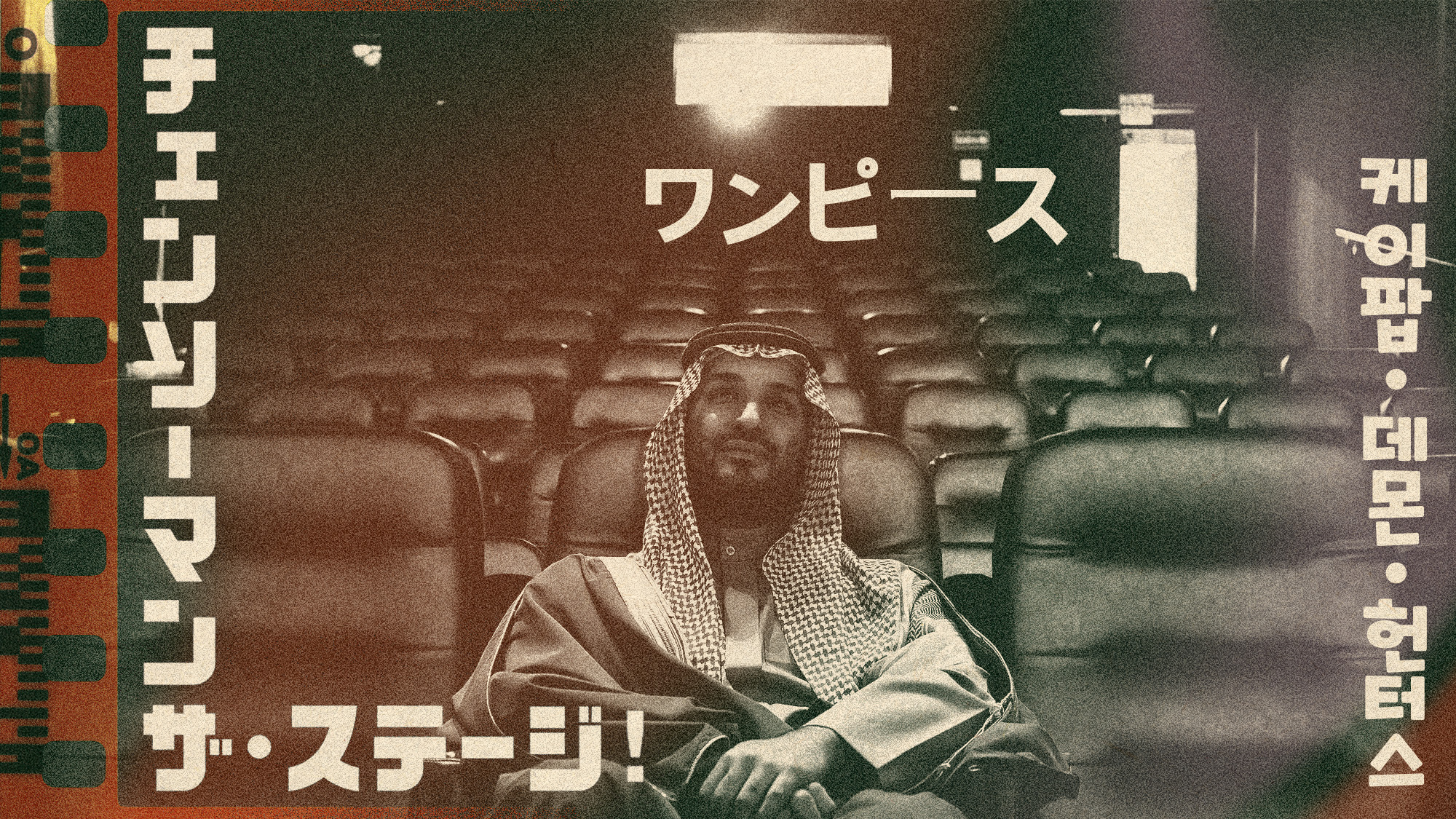

Why Saudi Arabia is muscling in on the world of anime

Why Saudi Arabia is muscling in on the world of animeUnder the Radar The anime industry is the latest focus of the kingdom’s ‘soft power’ portfolio

-

Scoundrels, spies and squires in January TV

Scoundrels, spies and squires in January TVthe week recommends This month’s new releases include ‘The Pitt,’ ‘Industry,’ ‘Ponies’ and ‘A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms’

-

Venezuela: The ‘Donroe doctrine’ takes shape

Venezuela: The ‘Donroe doctrine’ takes shapeFeature President Trump wants to impose “American dominance”

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy