Is Amazon too big?

Amazon took a giant leap forward in its quest to become the “Everything Store” with its acquisition of Whole Foods. Is that a good thing?

The smartest insight and analysis, from all perspectives, rounded up from around the web:

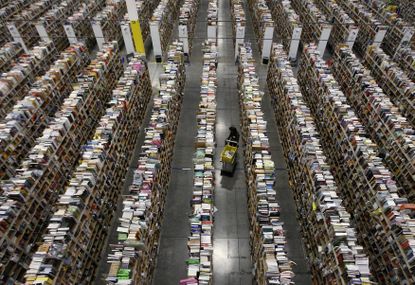

Grocery shopping may never be the same, said Davey Alba at Wired. Amazon took a giant leap forward in its quest to become the "Everything Store" last week with its $13.7 billion, all-cash acquisition of Whole Foods. The deal, Amazon's biggest ever, isn't necessarily a surprise. Amazon "has been trying to crack the food delivery business for a decade." But while the online retailer has arguably perfected the art of putting dry goods on customers' doorsteps, it has struggled to do the same with fresh food. That could change quickly now that Amazon has access to Whole Foods' sprawling supply chain, as well as its 431 stores — most of them in wealthy areas — which could soon double as pickup points for online orders.

In the near term, this deal is pretty straightforward, said Derek Thompson at The Atlantic. "Amazon needs food and urban real estate, and Whole Foods needs help." The upscale supermarket's revenue growth has tumbled every year since 2012, and investors have been pushing loudly for a sale to a larger grocer as the stock has nosedived. Amazon is "the perfect net." But in the longer term, this deal "is about Amazon as a 'life bundle,' particularly for affluent Americans." Amazon Prime has already become like the cable bundle of old — "merchandizing convenience" with streaming entertainment and fast, free delivery. More than half of U.S. households with income over $100,000 a year are already Prime subscribers. With Whole Foods in the mix, Amazon's dominance of the coveted "yuppie market" should only grow.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Amazon's takeover of Whole Foods sent the stock of competing grocery chains plummeting," said Matthew Yglesias at Vox. But then, it's hard to compete with a rival that doesn't seem to care about making money. It's not unusual for Amazon to report nearly zero in net income in quarter after quarter as the company plows money into developing new businesses, whether it's producing original TV shows or building artificially intelligent speakers. Whole Foods under Amazon will almost certainly accept lower profit margins than it does now, "and that spells trouble" for nearly every other grocer in an industry already infamous for its razor-thin margins.

It's not just groceries — Amazon is on the verge of swallowing our entire economy, said Alex Shephard at New Republic. Usually a firm's stock price drops after it acquires a troubled business. Amazon's surged, suggesting that Wall Street thinks the company "is so powerful that anything standing in its way is toast." Last year, Amazon sold "six times as much online as Walmart, Target, Best Buy, Nordstrom, Home Depot, Macy's, Kohl's, and Costco did combined," said Robinson Meyer at The Atlantic. It rents server space and computing power to Netflix and the federal government. It "lends credit, publishes books, designs clothing, and manufactures hardware." Consumers may love the convenience of having their groceries, entertainment, and more delivered right to their door. But it may not be long before we start asking ourselves whether Amazon "is just too big."

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Today's political cartoons - May 5, 2024

Today's political cartoons - May 5, 2024Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - annoying noises, gag orders, and more

By The Week US Published

-

5 highly educational cartoons about student protests

5 highly educational cartoons about student protestsCartoons Artists take on apolitical camping, the National Guard, and more

By The Week US Published

-

French schools and the scourge of teenage violence

French schools and the scourge of teenage violenceTalking Point Gabriel Attal announces 'bold' intervention to tackle rise in violent incidents

By The Week UK Published

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

By Peter Weber Published

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

By Brendan Morrow Published

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

By David Faris Published

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

By The Week Staff Published

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

By Tonya Russell Published

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

By Noah Millman Published

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

By The Week Staff Published

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy

By Jeff Spross Published