The secret life of urban crows

Crows are incredibly clever birds, capable of using tools and recognizing faces. Researchers have even found that crows mourn their dead and hold 'funerals.'

On a blustery overcast morning this past April, Kaeli Swift walked across the campus of the University of Washington toting a weathered purple-and-white plastic shopping bag. This bag, if found by some unsuspecting student or groundskeeper, would almost certainly trigger a campuswide panic. Inside, Swift had stowed a rubber mask of a grotesque, exaggerated male face — large ears, bulbous nose, silver-whiskered soul patch — a guise that would not look out of place in a 1980s horror film. Also inside: a corpse. That the corpse was only that of a bird didn't make the tattered bag's combined payload any less creepy.

She tromped through the wet grass in calf-high Sorel snow boots and made her way to the university's Center for Urban Horticulture, where she's a teaching assistant for an undergraduate natural history class. Near the dumpsters and trash cans parked behind the center, Swift found a perfect spot for what she was about to do: perform a ritual that, depending how you look at it, is a couple of years old or a couple million.

Swift, a Ph.D. candidate, is a member of UW's nationally acclaimed Avian Conservation Lab. If you've heard or read a news story in the past decade about Corvus brachyrhynchos — aka the American crow — and what science has to say about its confounding habits and aptitude, there's a good chance it was thanks to the work conducted by the lab, which is led by a man named John Marzluff. The UW professor and wildlife biologist is the author of numerous popular books on the subject. In 2008, Marzluff and his fellow researchers made national headlines when they tested a hypothesis — that crows recognize individual human faces — by donning Dick Cheney masks. That led to another revelation: Crows teach other crows to detest specific people (and sometimes attack them).

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Today, Swift, 30, would repeat an experiment that uncovered one of the team's more staggering revelations. And she conducted it with the ceremony of an undertaker.

From the old shopping bag she unsheathed the dead crow and turned it in what little sunshine strained through the fibrous clouds. The black feathers sparkled in the light, and close inspection revealed iridescent blues and purples. She covered it back up with a tan cloth, and with the draped bird lying breast down on her two upturned palms, stepped gingerly onto a patch of grass. She tore the linen away and unveiled the corpse to the gray heavens.

There was nothing at first, just an empty sky. Then, a caw. A crow appeared on a nearby power line. Then another caw and another crow. Suddenly crows flew in from all directions. Their plaintive cries soon combined into a chorus. New arrivals joined what quickly grew into a cacophonous dervish of black silhouettes swirling directly above Swift.

It was like sorcery. Conjuring dozens of birds from thin air by simply removing fabric from a body.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This, according to Swift, is what it's like to attend a crow funeral — an instinctive ritual that evolved generations ago and was just discovered by humans; Swift co-authored an article on her findings in the journal Animal Behaviour in 2015. The gist: Upon spotting one of its dead, the flock attends to the fallen bird en masse with loud shrieking. Given enough time, the throng will mob any predator it thinks is responsible, like, say, a human in a Dick Cheney mask, or in a mask like the one Swift had in her bag. (The lab affectionately refers to that be-soul-patched fellow as Joe.)

Because she had decided to leave Joe out of today's repeat of her groundbreaking experiment, she had to take precautions. Early during this gathering tsunami of sound, once the crows became particularly agitated, Swift pulled the hood of her rain jacket over her face, lest the birds, days later, recognize that face.

When I came to Seattle, it was pretty obvious that the corvid of the day here was the crow," Marzluff told me recently. He was hired away from Boise State by the University of Washington in 1997 to teach and to study corvids, the family to which crows belong. (Jays, ravens, and magpies are also corvids.) Marzluff narrowed his focus once he observed just how many American crows lived and thrived in Seattle. The city's rapid growth and unique geography — it's essentially a forest squeezed between two bodies of water — are key to that large crow population. Forests aren't ideal for crow life, but over the past century we've carved and opened up these areas for our suburbs and provided a constant food source — namely, abundant edible trash. We've created what Marzluff calls "a mecca for crows."

What's more, due to the constant exposure to urbanites, crows here are virtually unafraid of humans. "In the countryside there are hunting seasons on crows," Marzluff says. And farmers harass and shoot them to protect their crops. In the city, we either ignore them, feed them, or turn them into icons. Either way, crows here are cued into our daily rhythms and feel safe among us.

That's certainly the case on the campus of the University of Washington, where up to 78,000 students, faculty, and staff spend their days. An early challenge for Marzluff, as he and his colleagues got the lab started, was capturing the campus fowl. (They're not afraid of us, but that doesn't mean they like being nabbed.) The team first tried a complicated makeshift trap involving a pizza box, leg nooses, and a weight. Later, and more successfully, they employed net guns to envelope the birds whole. As they apprehended each crow, the researchers placed a color-coded band on one of its feet, in order to tell the birds apart, and then set it free.

This opened a portal into crow life, permitting researchers access to what felt like another dimension, the crows' dimension.

"We were watching to see what they eat," Marzluff recalls, "and basically they will eat anything — and they will try everything." The birds would, for example, loiter around garbage cans and wait for a squirrel to squirm into a can and pop back out with food. The crows would mob that squirrel and steal its lunch. "I remember one time seeing them eat vomit off the side of a wall," Marzluff says. "You just go, 'Wow, really?' But they're very opportunistic and they make do with just about any scrap in the city you can imagine."

He details the birds' resourcefulness and ingenuity in a 2012 book he co-authored, Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave Like Humans. In it, we learn that not only do the birds recognize human faces and hold grudges for human misdeeds, but they also teach other birds to recognize grudgeworthy mugs. Fledglings, for example, watch their parents mistreated, hear the cawing associated with it, and learn to despise that human in the same way.

On the other hand, Marzluff writes, crows show great appreciation for humans who treat them well. "Gifts left behind are intended to court or impress people important in a crow's life." These gifts have been known to include candy, keys, and coins.

She was 8 years old and she had trouble reading. The Spokane elementary school she attended in the mid-1990s wanted to hold her back a grade. Was something wrong with her? Sometimes she wondered. The pediatrician had her on Ritalin. She hated Ritalin. It left her feeling separate, other.

She was a curious girl, though, and the wildlife in the hills around Spokane kept her rapt. She pushed herself to read so she could learn more about it: the Sawtooth wolf pack, which stalked the mountains of nearby Idaho.

By the time her family moved to the Seattle suburb of Mercer Island in the early 2000s, Kaeli Swift could read, had kicked Ritalin, and knew science was her jam.

She zeroed in on birds, and corvids in particular, as a biology major at Willamette University, in Oregon. She joined Marzluff as a graduate student at UW in 2012.

Now she's standing in a back lot of the university on a cloudy April morning holding a dead bird and re-creating her most important experiment as perturbed crows orbit, screeching and scolding.

It's hard to overstate the intensity of this experience. Nearly 30 banshees freaking out. They're 20 feet above, where they have the advantage of height and numbers, and all their attention and ire is directed at you. The nerve-fraying shrieks blast from every direction. A crow funeral is disorienting, a bit scary, and more than a little awe-inspiring.

This morning the noise has drawn out a university maintenance worker from behind a utility building. He's tall, sports a short white beard, and wears a bright orange safety vest. Is he here to admonish Swift for all the noise? Just a casual, awestruck observer? It's hard to tell. She's had the occasional run-in with angry people during her experiments throughout the city. She's even had the cops called on her. Trying to talk over the din would be pointless, it's so loud. So the man stands there, expressionless.

Swift says her funeral study demonstrates how crows process death and then warn one another about potential dangers. A dead crow, clearly, means something bad has happened to a crow. The presence of a potential predator, be it a bobcat, Joe with the soul patch, or Swift walking around on a Thursday, appears to make their warnings all the more urgent.

Years ago, Swift will later confess, she bonded with a female crow she had studied on campus, identifiable by its green and orange band. Scientists, of course, are discouraged from connecting emotionally with their subjects, lest it harm their objectivity. But it turned out this crow's territory was Swift's campus-adjacent bus stop. She had named the crow Go (its partner was Stop), and long after the study was over, Swift began feeding Go while waiting for the bus, where every day the crow waited for her. Go was old, at least 14, Swift estimates (crows can live up to 20 years), and she admits she became quite attached to the bird.

Last July a colleague informed Swift, over email, that Go had been found dead on campus. "That just sort of, like, broke my heart in such a deep way," Swift says.

Loss, of course, is at the core of Swift's funeral study. How do intelligent organisms deal with it? How do we cope? She says that when her grandmother died recently and she attended the funeral, she didn't know what to do with herself. She worried that her clinical view of death — she is, after all, a wildlife biologist — might come out and upset her family.

At the same time, Swift treats the deceased participants in her work with a dignity not typically associated with scientific research.

When she finally covers up the dead crow in today's re-enactment of her funeral experiment, it's with a gentle precision, as if the linen were a religious shroud. At that, the birds slowly grow quieter. Without one of their own to mourn, the circle above thins, and some crows retreat to a power line or disappear altogether. Light cawing remains, but a person can now hear herself talk.

The orange-vested university maintenance worker drawn in by the commotion still stands nearby and is still hard to read. He takes a wary step toward Swift. A kind of "What magic is this?" wary step.

Before he speaks he looks up again at the emptying sky, and back down at the 30-year-old woman standing in Sorels and placing a dark object back into a shopping bag. "Did you do all that?"

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in Seattle Met. Reprinted with permission.

-

Lebanon selects president after 2-year impasse

Lebanon selects president after 2-year impasseSpeed Read The country's parliament elected Gen. Joseph Aoun as its next leader

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Jimmy Carter honored in state funeral, laid to rest

Jimmy Carter honored in state funeral, laid to restSpeed Read The state funeral was attended by all living presidents

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

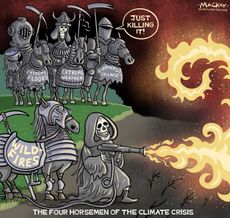

Today's political cartoons - January 10, 2025

Today's political cartoons - January 10, 2025Cartoons Friday's cartoons - killing it, kicking it, and more

By The Week US Published