Are cars really going to disappear?

Don't bet on it

Are we really only a few decades away from seeing the end of cars?

By "cars," I mean what the New Oxford American Dictionary defines as "a road vehicle, typically with four wheels, powered by an internal combustion engine and able to carry a small number of people." You know, cars. They run on gasoline or diesel fuel. They can be loud and painted cool colors and you can go really fast in them while listening to music (often music about cars). In movies starring Robert De Niro or Vin Diesel they often chase one another and explode. You take them to the gas station to make them go, not to the power outlet in your garage where you have all your saws plugged in.

But many politicians and scientists insist that cars are about to go the way of the horse and buggy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Michael Gove, the British environmental secretary, announced on Wednesday that beginning in 2040, the sale of all motor vehicles powered by gas or diesel would be banned in the United Kingdom — and the use of such vehicles on roads would be prohibited outright by 2050. Gove's announcement followed on the heels of similar declarations in France, where President Emmanuel Macron is committed to a ban within the same timeframe, and in India, which has committed to ending sales of non-electric vehicles only 13 years from now.

It's hard not to see these deadlines as ill-thought-out and arbitrary, empty point-scoring gestures that may not come to anything. At present, electric vehicle sales make up less than 3 percent of the British car market. Meanwhile, there are more than 31 million cars on the road in Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (Though there would probably be fewer of them if it were not for the disastrous privatization of British Rail under Prime Minister John Major in 1994.)

Where are all of these cars going to go? Will people have money to replace them with brand-new electric-only vehicles? A car like the Hyundai Ioniq Electric starts at £30,000, or just under $40,000. Drivers can expect to get only about 150 miles out of it per charge. These cars will have to get substantially cheaper, either because automakers will be able to manufacture them for significantly less or thanks to a government subsidy. It will probably take both.

It is also entirely unclear what exceptions might be made for farming equipment and other high-performance vehicles that do not have capable electric-only equivalents. If a farmer buys a tractor, will it have to go down Her Majesty's highways to his fields under heavy military escort? What about automobile racing? What about the substantial number of people who just happen to like driving fast powerful cool-looking machines? Clearly there are plenty of things that need to be ironed out.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The year 2040 might sound like a long way off, but 23 years ago it was 1994, when Kurt Cobain died and Newt Gingrich and the Republicans took over Congress and Al Cowlings drove O.J. Simpson around in a (gas-powered) Ford Bronco. Twenty-three years is really not that far away.

The ostensible reasons for urgency here are climate change and public health. Obviously, most of us will admit that pollution is bad and that it would be a good thing if there were less of it. And it's true that a move to mostly electric cars would result in a huge decrease in emissions no matter where the power is coming from.

I would go further and say that I think the automobile, while a useful tool for people who need to haul and tow and ship stuff and an indelible staple of post-war consumer culture, is mostly a bad thing. Its rise has abetted our most vicious antinomian habits. It made Detroit probably the worst-planned city in the Western hemisphere. It would be better if more of us were taking trains or bicycles or just walking.

Still, I think it is unlikely that anything like Europe's new anti-car push will happen in the United States soon. We are too culturally attached to cars, and everyone from the oil industry to the automakers to the hundreds of thousands of small businesses that would not exist without the car market as we know it will unite against any hard ban on traditional automobiles in this country. Besides, this is a huge country. One-hundred fifty miles won't get you from London to Manchester in a trip — imagine trying to do an old-fashioned American road trip from Toledo, Ohio, to Golden, Colorado, in an electric car. That's 1,250 miles. You'll have to plug your "car" in nine times. Nobody wants to stop that often. And all of that is to say nothing about the security of our power grids. What would happen if the Chinese or the Russians shut them down for two days?

If cars as we know them are really toast, perhaps it's time to invest in a horse.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

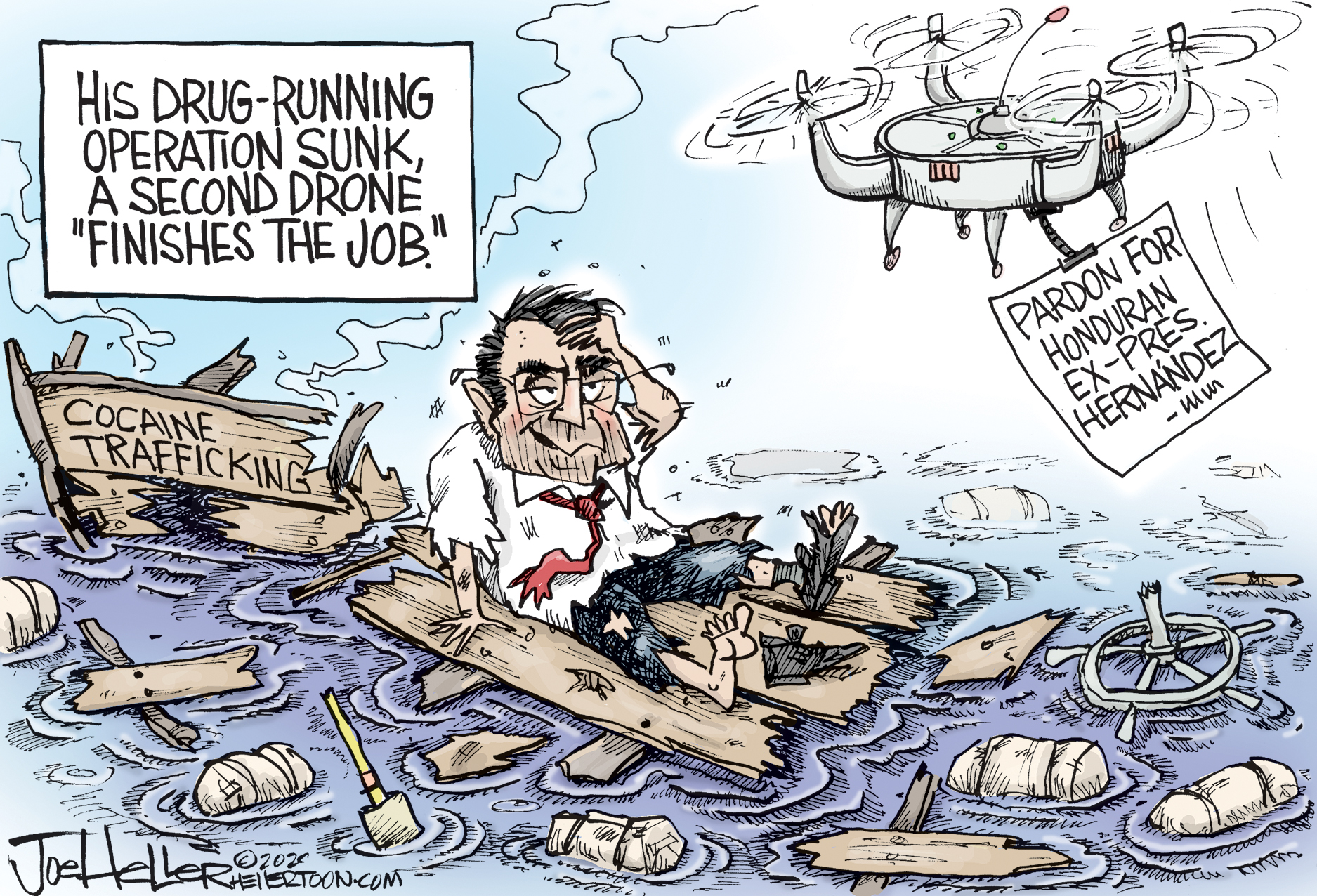

Political cartoons for December 6

Political cartoons for December 6Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include a pardon for Hernandez, word of the year, and more

-

Pakistan: Trump’s ‘favourite field marshal’ takes charge

Pakistan: Trump’s ‘favourite field marshal’ takes chargeIn the Spotlight Asim Munir’s control over all three branches of Pakistan’s military gives him ‘sweeping powers’ – and almost unlimited freedom to use them

-

Codeword: December 6, 2025

Codeword: December 6, 2025The daily codeword puzzle from The Week