America is still treating college sexual assault victims like they're stupid

Some arguments never change

Almost exactly three years ago, a sophomore, Hannah Graham, disappeared from the University of Virginia. In the weeks following her disappearance, Camille Paglia decided to weigh in at Time. College women were naïve about the world; they didn't understand evil or violence. "The price of women's modern freedoms," she wrote, "is personal responsibility for vigilance and self-defense."

Paglia's article represents the extreme end of a genre you could call "Real Talk, Ladies!" It tells college-aged women not to drink, to scrutinize their actions for possible sexual overtones, and not to trust their friends. It often appears in venues where it's hard to imagine college students reading it. (Who, exactly, are the college freshmen looking for "straight talk" from The Wall Street Journal?) Any ugly consequences are as natural as gravity — yes, you can have a drink or go to a party, but if you do, you've opened yourself up to the consequences. So don't come crying to me when you're raped.

College activists made campus sexual assault a national issue, but I'm not sure that's why the issue stayed there. In the weird world of the American opinion page, the university has come to stand for "community." If we want to talk about threats to freedom of speech, we don't pick the legislation in North Carolina making it legal to hit protesters with your car, but an op-ed in a student paper. And when we want to talk about sexual assault — whether we're picking up Laura Kipnis's Unwanted Advances ("listen up, ladies!") or Vanessa Grigoriadis's Blurred Lines ("I'm listening, ladies") — we talk about campuses, even though women on college campuses aren't more at risk than their peers. So college sexual assault stands in for sexual assault generally, even though any reform of Title IX itself will only affect a small part of the population.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Campus activists have every reason to keep up pressure on this issue — particularly now, since the guidance on Title IX enforcement is in the process of changing — but we should also ask why the rest of us are so willing to limit ourselves. Why, in short, are we so obsessed with college women?

There are a lot of possible answers — ranging from the crass ("college women are hot") to the darkly meritocratic ("women who don't go to college don't deserve the attention") to the boring ("students tend to stay engaged on this issue after they graduate"). Here's mine: Campus sexual assault is part of a coming of age story, or rather, these days, it's part of a story about failing to come of age.

In this story, what's at stake isn't consent so much as a girl's expectation about the way the world works. If we focus on the college girl as the typical sexual assault victim, it's at least in part because her anger is deemed a failure of her education. She's a stupid girl, lacking even in the common sense not to get raped. She didn't think the situation through. She's not learning from her experience, or at least not learning to accept it.

It wouldn't be quite accurate to say "it has been ever thus." But this story has been running thus since at least the late '70s, when one of the first sexual assault cases to employ Title IX, Alexander v. Yale, was taking place. Alexander v. Yale was, as these cases tend to be, a media event, covered glibly in Time ("Bod and Man at Yale") and sympathetically in The Nation. It also received a dry dismissal from Russell Baker in The New York Times, who asked why "the problem" was not "solved handily with a private initiative":

A robust father might have appeared carrying a shotgun at the office of one of the more obnoxious offenders. A large brother or boyfriend might have blackened his eye. A small woman might have cooled his passion with a hat pin, and only slightly clever small woman might have crushed his ego with a few simple words thrust neatly into his vulnerable asininity. [The New York Times]

Instead, Baker lamented, "to cope with the problem which her mother could solve in an afternoon, [a young woman] requires the aid of lawyers, a judge, a jury, witnesses, transcripts, three years of litigation, and two appeals courts." Your mother could hack it, so why can't you?

Almost 20 years later, the writer Katie Roiphe would go on to frame the difference as one between the tough feminism of her mother and the shrill feminism of her peers. Even Kipnis, in her recent book, fondly recalls a story of her mother being chased around a desk by her boss and shrugging it off. The generational refusal to take your lumps becomes a crisis. What's wrong with these women? They want so much, they make so many mistakes, and, above all, they're so weak.

But as the backlash cycle itself goes to show, these angry young women do have mothers, both intellectually and politically. The intergenerational conflict is real, but so is the existence of a solidarity that stretches across the generations.

Every stupid girl is taking a step into the world that could be. For that world, they're willing to risk a lot. They believe that people can be better; they believe we can expect more from each other. That's as much real talk as anybody could need. I hope we continue to live in a world full of women — in the university and outside it — stupid enough to keep asking for more, stupid enough not to accept things the way they are, and stupid enough to care.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

B.D. McClay is a senior editor at the Hedgehog Review.

-

Lebanon selects president after 2-year impasse

Lebanon selects president after 2-year impasseSpeed Read The country's parliament elected Gen. Joseph Aoun as its next leader

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Jimmy Carter honored in state funeral, laid to rest

Jimmy Carter honored in state funeral, laid to restSpeed Read The state funeral was attended by all living presidents

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

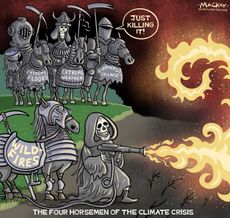

Today's political cartoons - January 10, 2025

Today's political cartoons - January 10, 2025Cartoons Friday's cartoons - killing it, kicking it, and more

By The Week US Published