Against public apologies

These pseudo-confessions, soaked in the language of therapy and addiction, offer nothing even approximating sincere contrition

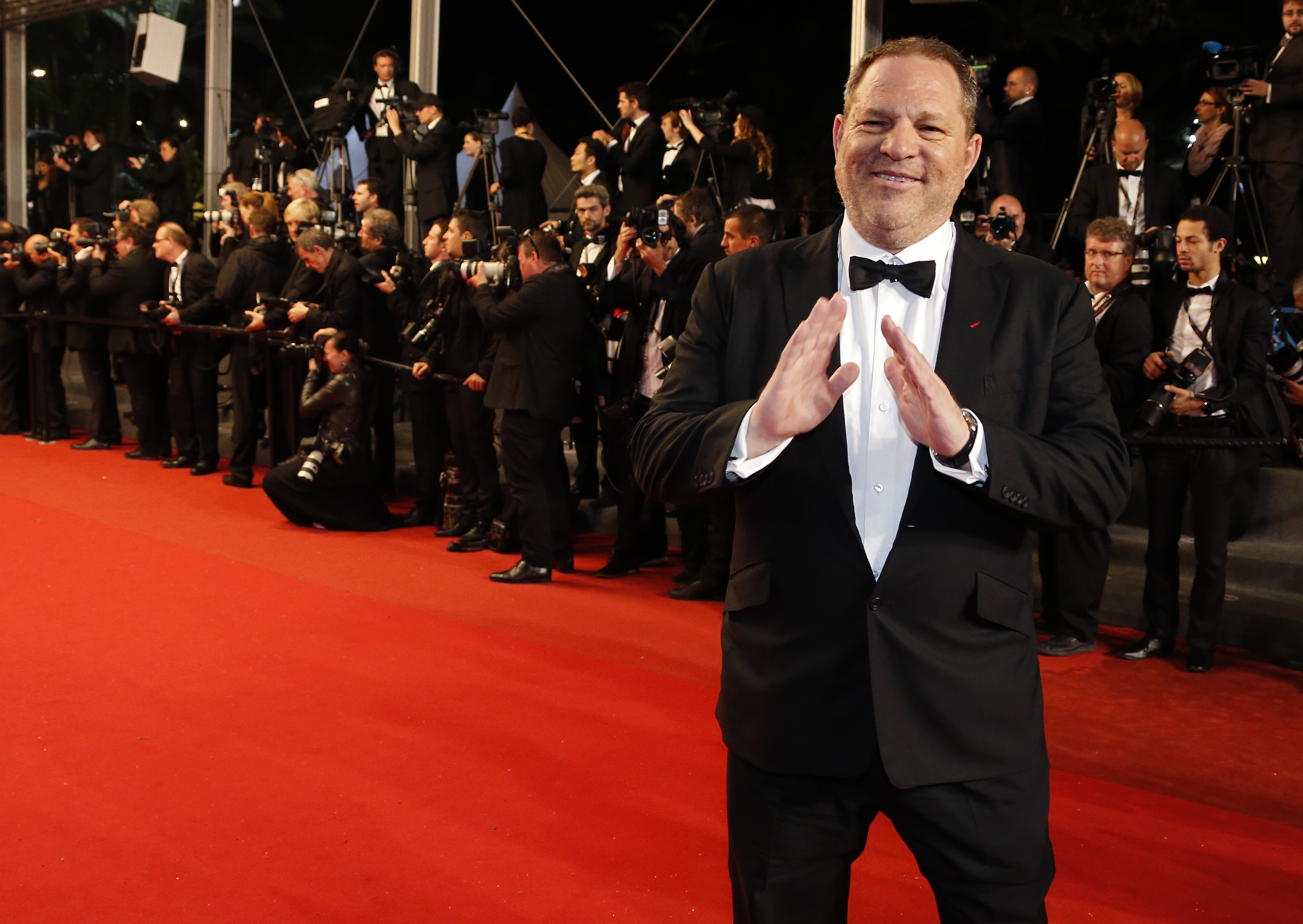

The only detail of possible interest to be gleaned from the one-page document submitted by Harvey Weinstein to The New York Times following the paper's explosive report alleging his decades-long practice of paying hush money to women who have accused him of sexual assault is that the veteran Hollywood producer, or whatever grave-faced functionary is responsible for drafting the man's public utterances, uses, on the evidence of the font, a post-2010 version of Microsoft Word. Otherwise his statement is almost willfully content-free.

It was meant to be. For years now, any time a public figure in this country is credibly accused of some terrific wickedness, their inevitable responses have been tediously uniform in style and content. The most striking feature is that these would-be apologies are almost never apologies.

To apologize is to express heartfelt contrition, and contrition is only possible when we feel bad not because our actions — or at any rate the fact of their being discovered by others — have exposed us to unpleasantness but because we recognize that they are fundamentally wrong. This is why when Catholics confess our sins we tell the priest that we are "heartily sorry for all our sins because we dread the loss of heaven and the pains of hell, but most of all because they offend Thee, O God."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Instead, what non-apologies like Weinstein's or the recent "statement" released by the office of Rep. Tim Murphy, the ostensibly pro-life Ohio Republican accused of pressuring his mistress to abort a child, do is absolve the persons to whom they are attributed of culpability for the wrongdoing to which they are not, in fact, confessing. They never refer to the actions in question, in part, no doubt, for reasons that could be explained by the well-remunerated graduates of prestigious law schools and public-relations professionals who are their real authors. These pseudo-confessions are soaked in the language of therapy and addiction; windy phrases about "the journey" and "my demons" abound; there is always an emphasis on how "sincerely" (has any genuinely sincere utterance in history ever carried that qualifier, I wonder?) the parodies of feelings being referred to are; parades of excuses are invariably lined up before our eyes so that we can be informed that they are, in fact, "not excuses."

After noting that he will not seek re-election, Murphy tells us that "in the coming weeks I will take personal time to seek help as my family and I continue to work through our personal difficulties and seek healing." Healing for what? Pancreatic cancer? Is exerting your considerable power as an influential member of Congress to suggest that a woman with whom you were committing adultery should consent to a practice that you have made a career out of equating with murder a disease? There is no alleged crime so vile that it cannot be excused if the person responsible for it is said to be "seeking help," no misdeed that cannot be pardoned by cursorily auto-exculpatory references to context. "I came of age in the '60s and '70s," Weinstein helpfully explains.

This is not to suggest that the circumstances under which we harm others do not matter when our guilt is assessed. But that is a question for judges, in this life and the next.

Just as predictable as the phony apologies themselves are the customary responses from their jaded consumers: not genuine disgust but a kind of gleeful hypocrisy-shaming.

I first became aware of the Times' report on Weinstein when I saw images of him with Hillary Clinton on Twitter. It would appear that to many of my fellow journalists the most salient fact about this man who appears to have made a career out of attempting to use his substantial financial resources to erase allegations of vicious behavior is that he has at some point in his life given financial assistance to a candidate for political office who also received the support of some 48 percent of American voters.

This rhetorical opportunism is not, I think, an incidental bit of boorishness. Indeed, I think it is likely that our shared allergy to contrition is in large part a result of how we have all been taught to think about evil in this country. The greatest sin of all in America today is hypocrisy; it is better to believe in nothing than to espouse certain principles and fail to live up to them. The most valuable rhetorical currency in our public disputes is to be able to accuse the other side of hypocrisy or proximity to it. "Think Hillary and the Dems are woke on women's issues? Eat this, libs." "Isn't it amazing that people who explained away Donald Trump's behavior towards women are seizing on this?" The tweets write themselves.

Like non-apologies, these proximity-based exercises of conscience won't go away until we decide that things are wrong because they are wrong.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

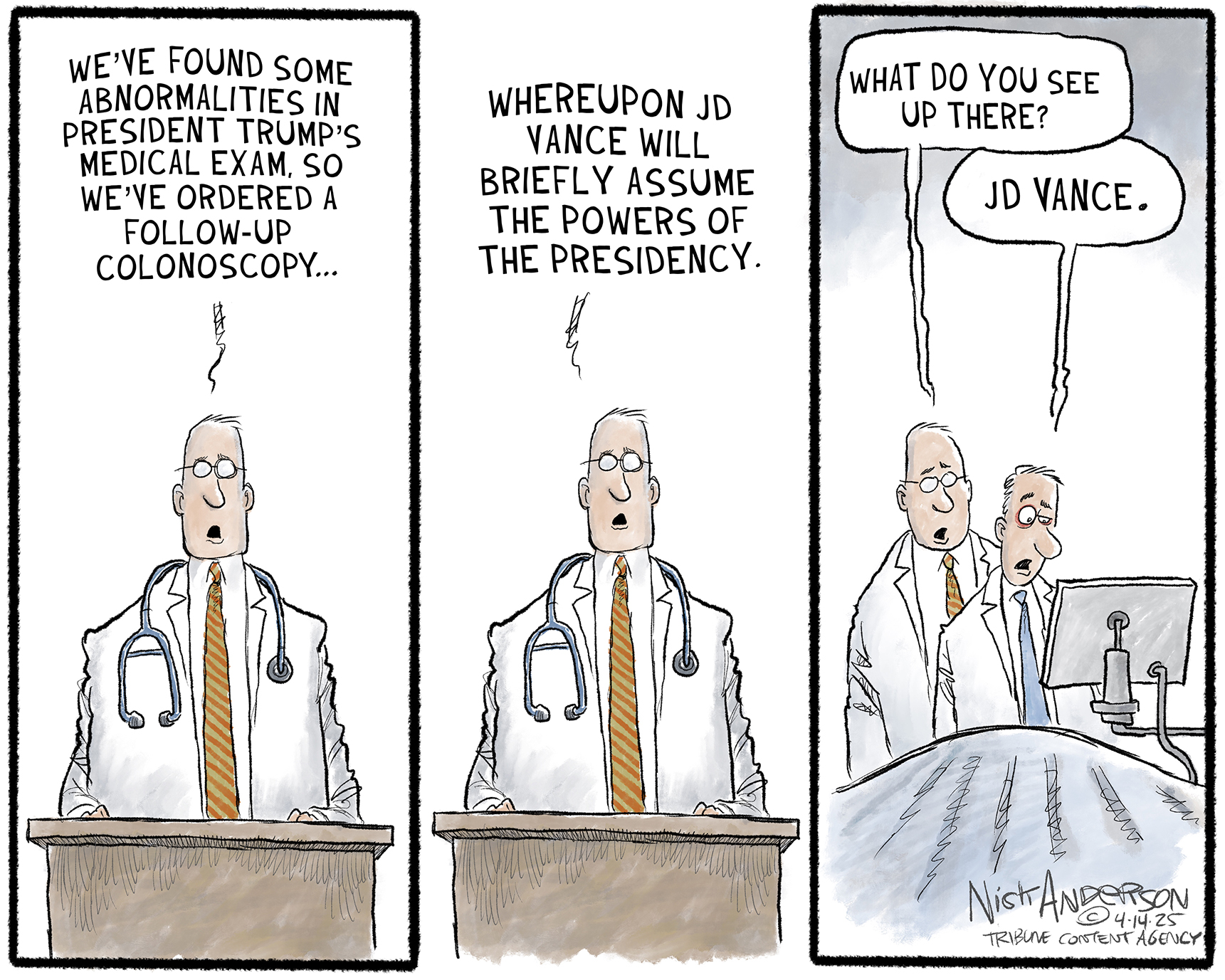

Today's political cartoons - April 16, 2025

Today's political cartoons - April 16, 2025Cartoons Wednesday's cartoons - Trump's medical exam, student loan debt, and more

By The Week US

-

Christian dramas are having a moment

Christian dramas are having a momentUnder The Radar Biblical stories are being retold as 'bingeable' seven-season shows

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK

-

Money dysmorphia: why people think they're poorer than they are

Money dysmorphia: why people think they're poorer than they areIn The Spotlight Wealthy people and the young are more likely to have distorted perceptions

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK