The nourishing radicalism of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and Jane the Virgin

If you're looking for something healthy in a media landscape that sometimes feels poisonous, watch them

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and Jane the Virgin returned last week, and not a moment too soon.

I'd like to say I'm writing about these shows right now, in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal, which revealed the wretched conditions under which female artists work in Hollywood, because it's so important to examine shows about women, by women. But that framing, while true, is so horribly medicinal. It sounds dreary, like an obligation. So let me say this, which is less pat but more true: I've been waiting anxiously for Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and Jane the Virgin to return because they're whip-smart, secret inversions of all the gender "scripts" and stereotypes and Hollywood archetypes that impoverish our media and our lives. They subvert pop culture's truisms about how abstract ideas like Man and Woman and Sex work. And — unlike shows like Westworld, which can sag under the weightiness of their ambition — they have fun doing it.

Here's why: The CW has made camp into art. Crazy Ex-Girlfriend takes a familiar genre — the musical — and indulges every one of its secret premises to the hilt, splashing in its pleasures and mercilessly exposing its absurdity. Creator and star Rachel Bloom is a modern-day Flight of the Conchords, composing songs that simultaneously perform and satirize their genres, and her critiques have gotten sharper and smarter as the show has gone on. Crazy Ex-Girlfriend's third season begins with Rebecca Bunch — the main character who left a high-paying job in New York to follow a middle-school crush — reinventing herself as the "woman scorned." She's been left at the altar, and there will be hell to pay. You can almost hear the tagline.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is a premise so familiar you can practically write the story yourself. We've seen it a million times. It's one of the most familiar "scripts" about broken women this culture has (second only to the "Crazy Ex-Girlfriend" herself). These narratives are the code of our culture, and they run, undetected, in our operating systems, governing much about how we think.

So the Crazy Ex-Girlfriend premiere does what every episode of this show does: treat the stereotype with unexpected understanding and empty it. True, Rebecca loves presenting herself as a vengeful butterfly who's emerged out of the cocoon of her abandonment: She's dyed her hair a darker color and reappears dressed all in white. She even explains that the dark hair represents her villainy and the white dress is ironic — it represents the bride she once was and contrasts with the evil contours of her present self. But her evil plan is so unbelievably sad that even her pals — who are usually up for indulging her — can't quite believe it. Her plan is to send him her poop in a box that's labeled "cupcakes."

This is the first of several instances in which a real woman fails to live up to the legends of her sex. Rebecca is working so hard to inhabit a narrative that gives her power — even if it's only as a deranged "femme fatale" — but it doesn't work. The pathos and pain are real, but the power is paper-thin.

A second set piece gloriously satirizes the "don't get me started about men" tendency. A song and dance number in which Rebecca and friends make increasingly unhinged assertions about men (it's called "Let's Generalize About Men") is constantly undermining itself: "Right now we're angry and sad. It's our right to get righteously mad. Every member of the opposite sex — oh god, we hate them. Let's not distinguish between them at all. Let's just drink a lot more alcohol, and then high-five each other as we make a bunch of blanket statements."

The chorus is basically about toxic gender scripts: "Let's generalize about men. Let's take one bad thing about one man and apply it to all of them."

The point of this episode — every episode of this series, really — is to reveal how disadvantaged the decentered party is in common cultural scripts. In this very particular and interesting case, the decentered party is Josh. Usually it's Rebecca — every episode of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend defaults not to her perspective but to his.

Jane the Virgin (which once did the opposite, centering "Jane Villanueva" to such an extent that the narrator almost worships her) approaches the same problem — the pernicious erasures made possibly by narrative centrality — differently. Jane the Virgin took the telenovela, one of the few genres that lets women be at the center — and analyzes and psychologizes it. But last season, it started to unravel. For one thing, it finally took the plunge and undid its title: Jane lost her virginity. Showrunner Jenny Snyder Urman remarked then that the show's name might change to reflect that; since Jane is no longer "the virgin," every episode might have to supply its own mini-title.

But the season premieres with a pretty amazing upset: There's a new narrator! And she's a woman, and her narrative loyalty is to some guy named Adam whom Jane used to date. The show that has always been about Jane, and centered her problems, now features two different narrators fighting for structural and narrative supremacy. It's amazing.

I wrote some time ago about "promiscuous protagonism" — about how there's been an explosion of television shows (mostly run by women) that reject the fetishistic centrality of the protagonist. As if in response to the never-ending stream of shows exploring the dark psyches of male antiheroes with searching intimacy, shows like Transparent, Getting On, Orange is the New Black, and Doll and Em were irreverent about a particular character's narrative centrality.

I used to think that Jane the Virgin and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend were a breed apart; these seemed like shows fixated on something closer to "restorative protagonism," which I think of as a principled centering of the person who's usually shoved to the margins. But in recent seasons, both showrunners have shown an interest in decentering their own stars. These shows register a capaciousness, a willingness to extend narrative sympathy and focus, that seems like a necessary corrective to the cultural attitudes that produced men like Harvey Weinstein (who saw only themselves) and the first wave of condemnations (which sorts people into victims and monsters).

If you're looking for something nourishing in a media landscape that sometimes feels poisonous, watch them.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn in

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn inSpeed Read Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns amid surging gang violence

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

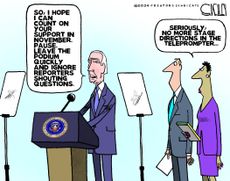

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - teleprompter troubles, presidential immunity, and more

By The Week US Published