How to fix the affordable housing crisis, big government-style

Uncle Sam needs to build, build, build

Affordable housing is dangerously close to going extinct. There are only 12 counties in the whole country where the average one-bedroom apartment is considered affordable for minimum-wage workers. And throughout the U.S., the stock of affordable housing is dwindling fast: Between 2010 and 2016, the amount of housing priced for very low-income families plummeted an astonishing 60 percent.

This is a crisis and it's high time American policymaking took it seriously. The federal government must get into public housing in a big way — and it needs to be smart about it.

The major cause of the crisis is that the collapse of job creation outside of major cities has sent demand for housing there sky high. And since the supply of land is fixed, and doesn't adjust to price changes like most goods or services, the price of housing just keeps soaring as well.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One popular fix among mainstream thinkers is to deregulate local zoning, roll back historic preservation rules, and the like. The idea is that these ordinances hold back construction, constricting supply. Cut the red tape, and let the market work its magic!

In and of itself, this certainly wouldn't be a bad change to make. But it's unlikely the market alone is up to fixing this problem.

Take San Francisco. Just to stabilize its insane prices, the city would have to increase its housing stock by 1.5 percent every year. But between 1967 and 2014, the city only got above 0.5 percent 17 times. It was able to briefly hit 1.3 percent in the late 1960s, when a lot of the land the city rests on now was still undeveloped. So you can see why hitting 1.5 percent on a regular basis with "infill development" — tearing down and replacing existing structures — is almost certainly a political, social, and physical impossibility.

Now, San Francisco is arguably the country's worst-case version of this problem. Other cities like Chicago or Washington, D.C., did at least temporarily stabilize prices with construction booms. But that's just stabilizing, as opposed to bringing those prices down, which is what really needs to happen.

This gets to another problem: For obvious reasons, private developers find it most profitable to serve the housing demands of the rich. "Most new construction of multi-family housing generally serves high-income renters," The Washington Post points out. This is foundational to the phenomenon of gentrification, among other things.

Private construction would have to build enough housing to satiate high-income demand first, before moving onto constructing more affordable housing units. But given the amount of money and wealth the rich have vacuumed up thanks to inequality, their potential demand for housing is enormous. In fact, since housing functions as a way to store wealth, including for international buyers who never plan on living there, that demand may be virtually insatiable.

This is the great virtue of public housing: The government is not a for-profit entity. It isn't constrained by the market forces that make a private construction boom focused on affordable housing such a hard financial lift.

That doesn't mean the government should just start building willy-nilly. The bad reputation of public housing is not unearned. A new era of it will require new and smarter strategies.

First off, a new public housing boom, even if it's administered at the state or local level, must be financed at the federal level. At this point, even affordable housing is expensive to build, and local and state budgets simply can't afford it. But the federal government controls the dollar, uniquely insulating it from the problems associated with deficit spending and debt loads. So it can just eat the costs of a genuinely enormous public housing boom.

As my colleague Ryan Cooper argued a few years ago, public housing should abandon the old model of giant apartment blocks. It should be dispersed across neighborhoods of all income levels, and it shouldn't look any different than the surrounding private housing. This would help avoid the problems of stigma and poverty concentration that have historically bedeviled public housing. The federal government can spend the money to meet higher quality levels, purchase empty lots or condemned properties, and even buy out existing structures in wealthier areas.

But the example of San Francisco also points to a deeper problem: Sometimes even a public housing boom may be unable to create the necessary housing stock within a city.

Such cases call for a more radical solution: Government efforts to create new urban hubs from the ground up.

Steve Randy Waldman points to Singapore and, to a lesser extent, Germany as countries that have succeeded here, and that the U.S. could learn from. This would not be easy by any stretch: Government efforts to "seed" new towns through housing construction would have to be linked to out-and-out industrial policy to "seed" new jobs and industries for these communities, along with establishing new research and development centers, new public universities, and so on. These new city hubs would also need to be near existing economic hubs like San Francisco, D.C., and New York City, and connected to them by big new public transit projects.

On the bright side, building new cities from the ground up would give urban policy experts a chance to put in practice everything they've learned about good density design, walkable living, and green infrastructure.

This last idea would obviously be a radical reinvention of existing American policy. But people seem to be responding to today's political division and economic stagnation with a new hunger for a big and bold proposals. This certainly fits the bill.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

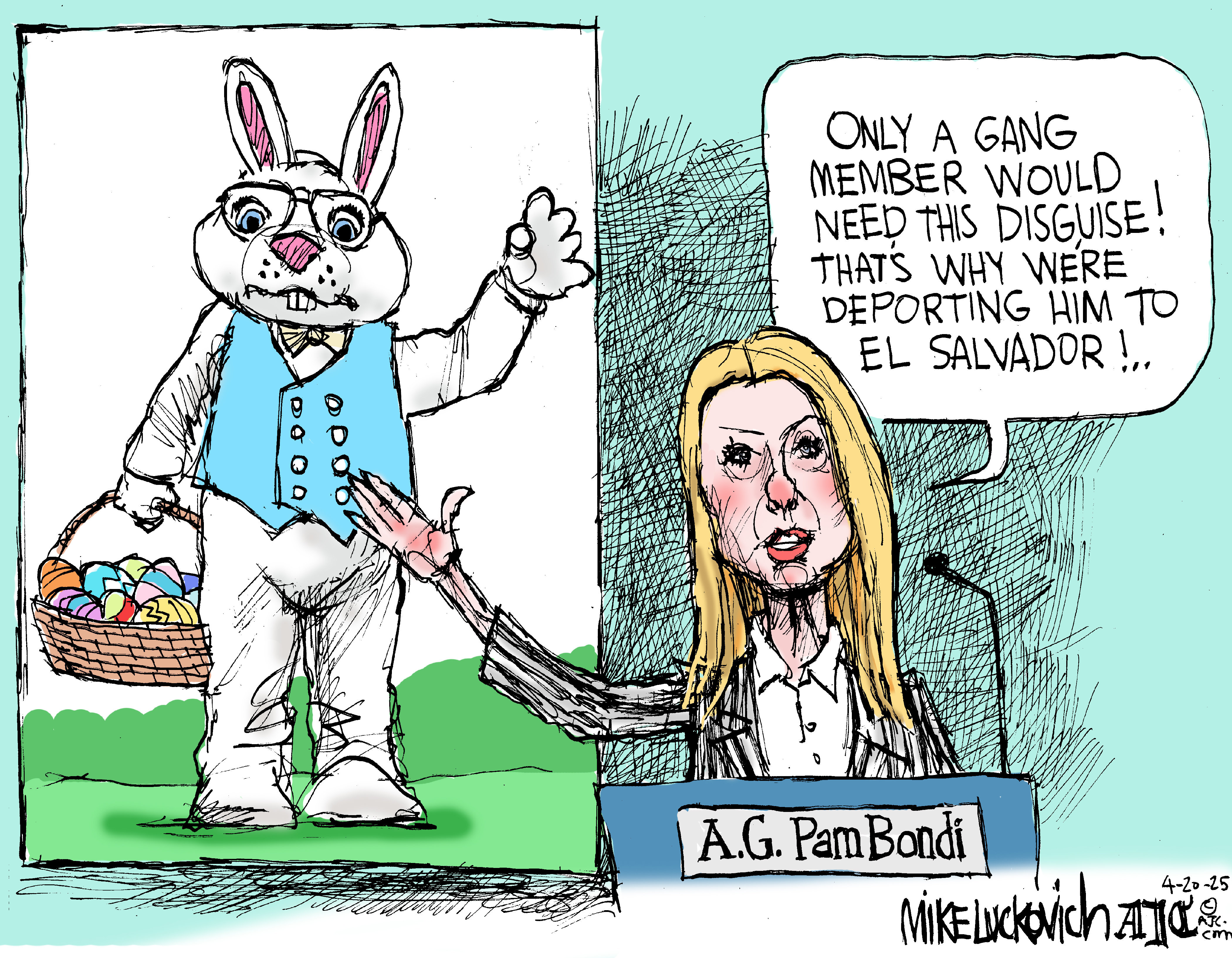

Today's political cartoons - April 20, 2025

Today's political cartoons - April 20, 2025Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - Pam Bondi, retirement planning, and more

By The Week US

-

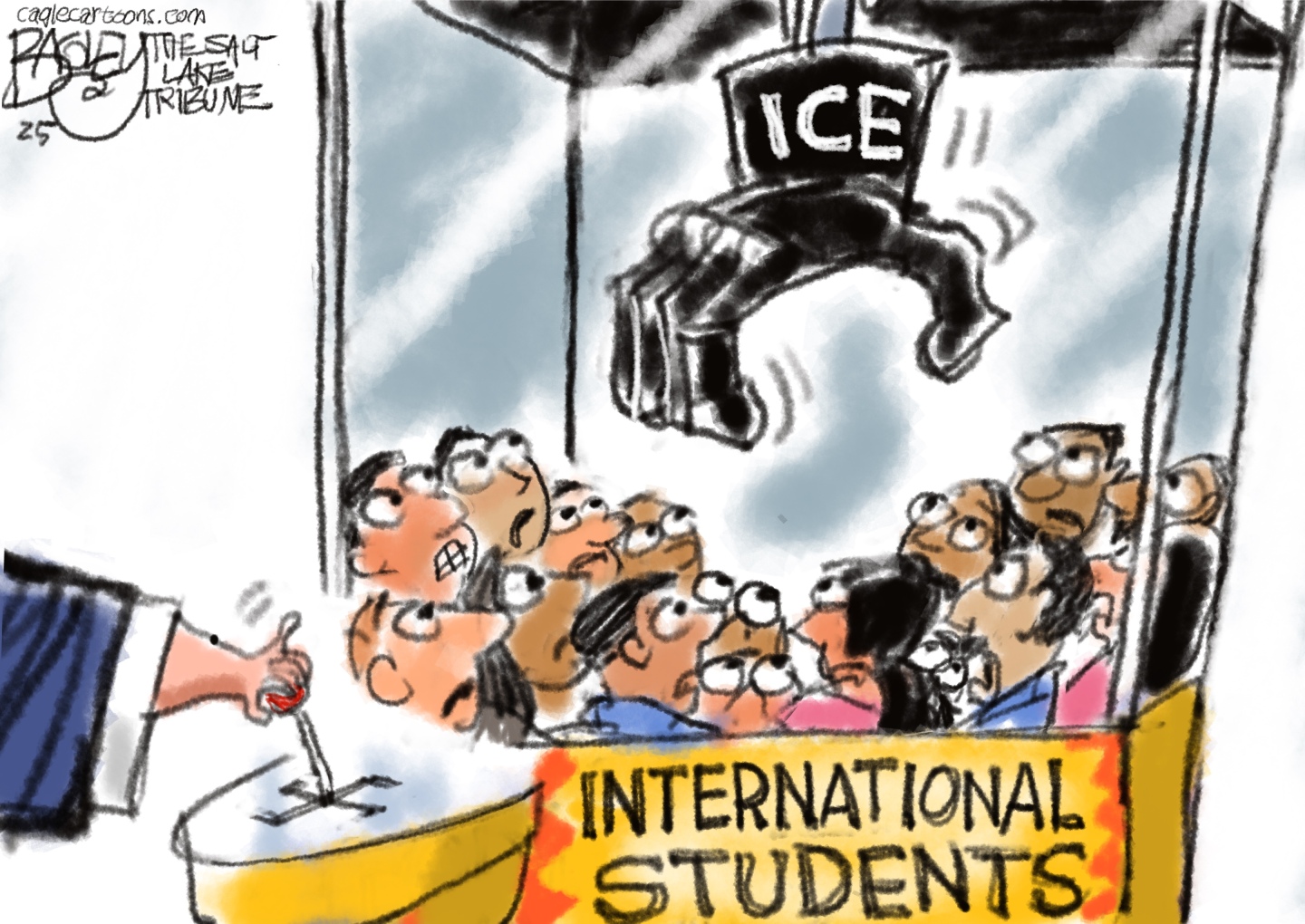

5 heavy-handed cartoons about ICE and deportation

5 heavy-handed cartoons about ICE and deportationCartoons Artists take on international students, the Supreme Court, and more

By The Week US

-

Exploring the three great gardens of Japan

Exploring the three great gardens of JapanThe Week Recommends Beautiful gardens are 'the stuff of Japanese landscape legends'

By The Week UK