Pope Francis and the saints next door

Francis' latest exhortation is the happiest piece of writing I have come across in ages

Every sentence of Pope Francis' latest apostolic exhortation contains medicine for our miserable world. It is not an accident that the text of Gaudete et exsultate ("Rejoice, and be exceeding glad," a quotation from the fifth chapter of St. Matthew's Gospel) was published on the Feast of the Annunciation, when Catholics celebrate the Blessed Virgin Mary's acceptance of her destiny to be the most important purely human being in all of history. This wonderful document is, above all things, a reflection on the importance not only of saying yes to what God asks of us — hope, faith, charity, the keeping of His Commandments — but of making our affirmations a cause for jubilation rather than an endless series of occasions for lugubrious grumbling. It is the happiest piece of writing I have come across in ages.

This is not a work of technical or academic theology but a practical treatise on holiness in the tradition of another of the pope's namesakes, St. Francis de Sales. The fact that very few of his readers indeed are prepared to read it this way is regrettable. The sort of Catholic who is programmed to detect heresy in every line attributed to the current occupant of the Petrine See and the other sort, loosely described by some as "liberal," who subsumes all of the faith into a passive-aggressive combat with the previous sort, will probably spend weeks shouting at one another over the precise meaning of the passage in which Francis reminds us that Catholics in public and private life are called to more than just opposition to abortion. The rest of us will come away with a feeling of extraordinary gratitude.

Francis is not aspiring to literature or even to the occasionally antiseptic clarity of earlier shorter papal documents (Blessed Pius IX condemned the whole of the modern world and all of its ills by name in his famously short and austerely written Syllabus of Errors). But there are nevertheless some very striking lines in the English translation — the Latin original, if one exists, remains so far unpublished. Anyone who is familiar with the lives of the saints will nod in agreement at Francis' observation that these luminaries "surprise us, they confound us, because by their lives they urge us to abandon a dull and dreary mediocrity."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It is this dullness, this painstaking tedious sanctimony that so often ends in despair that Francis contrasts with the cheerfulness and decency of authentic Catholic life. "Do not be afraid of holiness," he writes. "It will take away none of your energy, vitality, or joy." Indeed, so far from being a dour affair, "Christian joy is usually accompanied by a sense of humor." This is fitting. It is always worth pointing out that Dante called his great poem the Commedia — that, indeed, the whole of cosmic history in Christian terms is not a tragedy in which the hero is destroyed due to a regrettable misunderstanding or forces beyond his control but a comedy in the vein of P.G. Wodehouse in which the follies of a very large cast of buffoons are overcome by the efforts of a kind of all-seeing omnibenevolent Jeeves.

The older one grows the less important technical questions of theology seem for the ordinary Catholic, if indeed they ever mattered at all. There has never been a more pressing need for practical spiritual advice of the old-fashioned sort familiar to those who attend the oratories and chapels served by the canons of the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest. Hardly any sermons now address these questions; homilists regurgitate historical-critical gibberish they half-learned in seminary ("Now in Aramaic this word actually meant…") when they should be helping the faithful navigate the "rat race" of modern atomized existence," with its "endless array of consumer goods" and "constantly new gadgets." He is especially good on technology and the the constant temptation to "absolutize our free time, so that we can give ourselves over completely to the devices that provide us with entertainment or ephemeral pleasures." In response to this Francis implores us to commit ourselves to the Spiritual and Corporal Acts of Mercy: not only feeding the hungry and giving to the poor but bearing wrongs patiently and forgiving all offenses. In one memorable passage he imagines the thousand steps toward sainthood each of us is invited to take during an ordinary day:

A woman goes shopping, she meets a neighbour and they begin to speak, and the gossip starts. But she says in her heart: "No, I will not speak badly of anyone." This is a step forward in holiness… Later, at home, one of her children wants to talk to her about his hopes and dreams, and even though she is tired, she sits down and listens with patience and love. That is another sacrifice that brings holiness. Later she experiences some anxiety, but recalling the love of the Virgin Mary, she takes her rosary and prays with faith. Yet another path of holiness. Later still, she goes out onto the street, encounters a poor person and stops to say a kind word to him. One more step. [Gaudete et exsultate]

This is more valuable that a thousand windy discourses on the contextual meaning of Our Lord's rhetoric in the parables that all of us have heard in pulpits — to say nothing of passive-aggressive nonsense about the Christian duty to vote in meaningless elections.

It is somewhat grimly amusing now to recall the recent manufactured controversy over Francis' view of hell. If any modern pope has written or spoken more often about eternal punishment and the Evil One I would be astonished. Gaudete et exsultate ends with a very grim portrait of the Prince of Lies, who is emphatically not "a myth, a representation, a symbol, a figure of speech, or an idea," but a frightfully real and horrifying creature who cannot stand to see even one being made in God's image spend eternity with Him. It is almost ludicrous to recall that on Good Friday thousands of adult — largely male — "conservative" or "traditional" Catholics were spending time on the internet pretending that this man does not believe in eternal punishment.

But it is the emphasis on the possibility of charity and goodness in our fallen world rather than the infernal reality of Satan that will endure longest in the minds of readers. This is especially true of Francis' reflection on what he calls the "saints next door." We have all known such people. What is astonishing is their absolute variety. No two are ever alike in any outward sense save for the bare facts of their life-enhancing charity.

One of the holiest men I have ever met was the divorced professor of English at a bottom-tier state university who served as my sponsor for confirmation. He had left seminary in the late '60s in order to marry, only to be left by his wife decades later. Ray did not respond to this turn of events with despair. Indeed, I never once heard him say an unkind thing about anyone. Toward earnest undergraduates, not all of them exceptionally clever, he was endlessly patient and often helpful. He never entered a room without making a joke or doing something selflessly useful for at least one person in it. Evil and malice seemed wholly alien to his nature, as if they were unstable elements somehow introduced from another dimension — but he did not respond to them with melancholy or dejection. It was entirely unsurprising that the cheer and assistance, often unobtrusively material, he brought to thousands of people was fortified by the frequent reception of Holy Communion; Ray attended Mass daily and spent most of his evenings in silent prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. His life was an uninterrupted series of "nameless unremembered acts / Of kindness and of love," to quote a very long poem I once heard him rattle off from memory. "The holiness to which the Lord calls you," Francis writes, "will grow through small gestures."

The Holy Father's exhortation reminds us of the simple fact that we are all called to be saints next door as well as in heaven, and the plain truth that he is a good and pious shepherd of souls.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

The Nutcracker: English National Ballet's reboot restores 'festive sparkle'

The Nutcracker: English National Ballet's reboot restores 'festive sparkle'The Week Recommends Long-overdue revamp of Tchaikovsky's ballet is 'fun, cohesive and astoundingly pretty'

By Irenie Forshaw, The Week UK Published

-

Congress reaches spending deal to avert shutdown

Congress reaches spending deal to avert shutdownSpeed Read The bill would fund the government through March 14, 2025

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

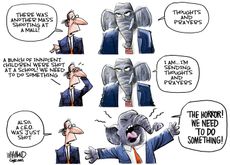

Today's political cartoons - December 18, 2024

Today's political cartoons - December 18, 2024Cartoons Wednesday's cartoons - thoughts and prayers, pound of flesh, and more

By The Week US Published