If America wants to stop the migrant crisis, it should decriminalize drugs

The drug trade makes millions for murderous gangs. It's time to put a stop to it.

President Trump put a damper on his infamous baby prison camps last week with an executive order ending his child separation policy. It seems like a step in the right direction — though there is as yet no process for reuniting the families, and it also appears to be designed to run afoul of a previous federal ruling that families themselves can only be detained for 20 days, thus setting Trump up to restart separating families and blame it on the judiciary.

The monumental heartlessness of separating families has rightly garnered overwhelming media attention. But it's worth stepping back to examine just why people are seeking asylum in America in the first place. They are, in the main, fleeing violence and political instability — problems which could be powerfully alleviated by decriminalizing illegal drugs in the United States.

The major population of refugees entering the U.S. are coming from four countries in Central America: Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, which comprise the "Northern Triangle." Violence there is apocalyptically bad — especially in El Salvador, where the murder rate was an eye-popping 60 per 100,000 in 2017 (and that is itself a sharp decline from 81.2 in 2016 and over 100 the year before that.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

By way of comparison: El Salvador is about the same size as Denmark, both with roughly 6 million inhabitants. But the 6,657 murders in El Salvador in 2015 amount to 190 times the number suffered by Denmark that same year — indeed, more even than the entire European Union put together.

Then, of course, there is an ungodly amount of assault, rape, burglary, kidnapping, and extortion.

Incidentally, all this should add some important perspective to the idea that asylum seekers need to be "deterred" from making the attempt to come to the United States (endorsed most notoriously by Trump adviser Stephen "Waffen-SS" Miller, but also Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton). Just about anything is worth chancing when one is facing down the possibility of being decapitated or dissolved in acid by gang assassins.

What's driving the crime? In brief, these countries have a severe gang problem, rooted in the drug trade and decades of political instability. The United States bears a great deal of responsibility for both. The U.S. started and then fueled a decades-long civil war in Guatemala that killed some 200,000 civilians. It fueled the 12-year civil war in El Salvador with money and arms. It armed right-wing death squads in Nicaragua that used Honduras as an operating base. Most of the big gangs are directly descended from demobilized soldiers and militias.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Then there is the drug trade, which is a major profit center for gangs. Central America is the biggest conduit for cocaine coming from growers in South America to customers in the U.S., and trafficking is both immensely profitable and the cause of violent turf wars. Again the U.S. both created the conditions for drug profits through its domestic drug prohibition policy, and directly fueled violent conflict by pushing a policy throughout the region of attacking drug gangs with the military. Disrupting existing gangs turned out to actually escalate violence dramatically, as new gangs fought to control the vacated territory and business.

It's hard to imagine how the United States could directly help these struggling states build strong institutions. Given our abysmal record in that department, probably the best thing we could do is leave them alone.

However, we could quickly and easily delete the major gang profit source by decriminalizing drugs like cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine. There are many different ways to do it — personally I would favor a prescription-based method, where addicts certified by a doctor can receive a supply made by a government monopoly, because under no circumstances can for-profit private businesses be allowed to deal in such addictive substances — but the foreign policy goal would be to somehow remove the drug supply business from the black market. With that established, evidence-based addiction treatment policy can set to work.

It wouldn't get rid of gangs overnight, as they have many other sources of revenue. But it would kick out one of their strongest props at a stroke, and just maybe shift the balance of power between the ordinary people of Central America and the gangs.

Over the last decade, there has been a remarkable loosening of attitudes on softer drugs like marijuana and psychedelics, many of which show remarkable medical promise. There is not much positive use for dangerous hard drugs like cocaine, heroin, and meth. But there is also no getting rid of them permanently (as decades of prohibition have proved beyond question), and a more sensible drug policy can help the beleaguered people of Central America, while at least doing no worse for drug abuse than the status quo. It is the least we could do.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Why is Donald Trump suddenly interested in Sudan?

Why is Donald Trump suddenly interested in Sudan?Today's Big Question A push from Saudi Arabia’s crown prince helped

-

X update unveils foreign MAGA boosters

X update unveils foreign MAGA boostersSpeed Read The accounts were located in Russia and Nigeria, among other countries

-

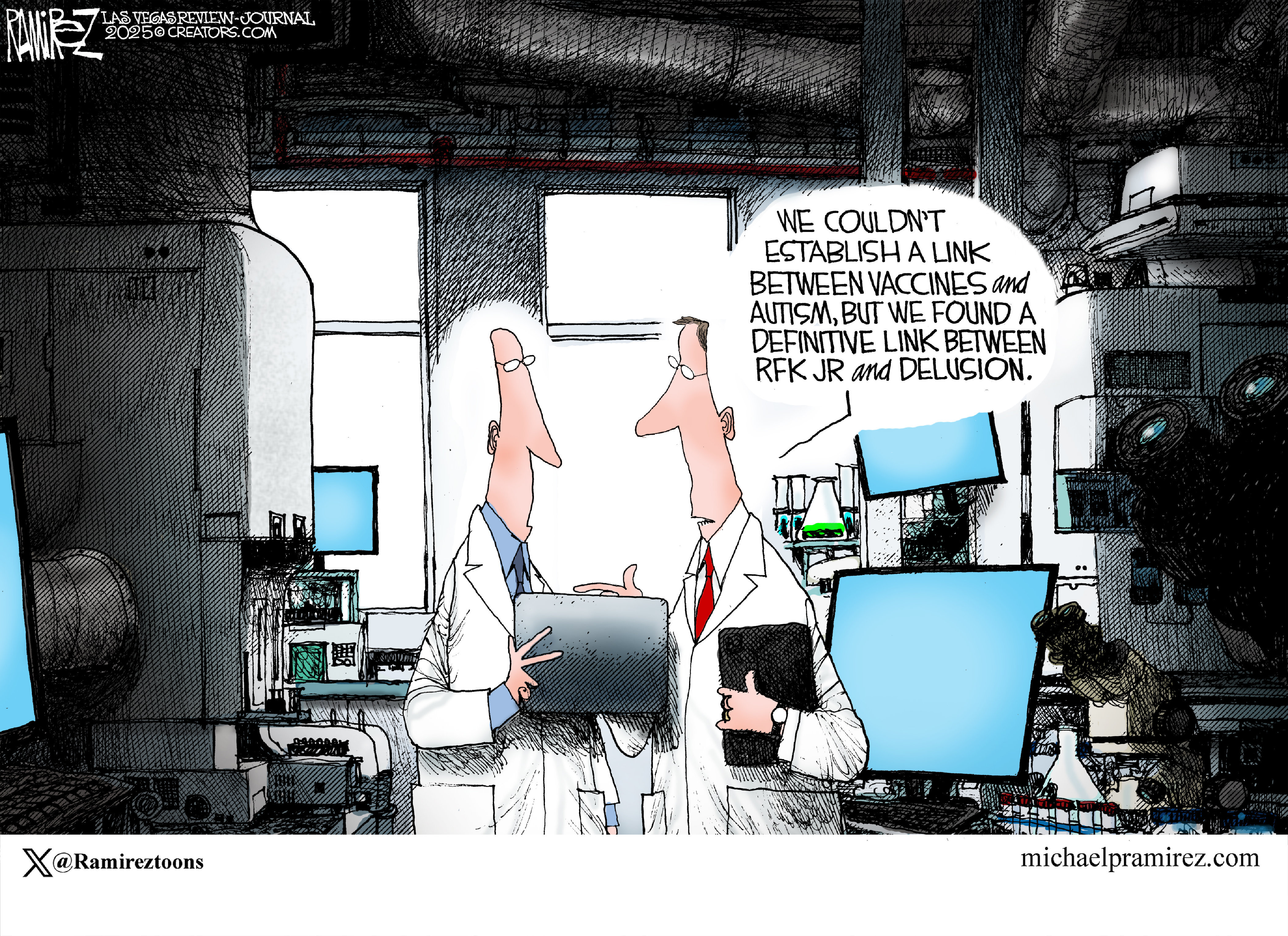

Political cartoons for November 24

Political cartoons for November 24Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include vaccine falsehoods, agreement on Epstein, and comedy with James Comey