How the Iranian Revolution unfolded

The nationalism-inspired overthrow of the royal family 40 years ago sparked a major shift in Iran’s relationship with the outside world

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Forty years ago this week the people of Iran voted to end centuries of royal rule and create an Islamic Republic.

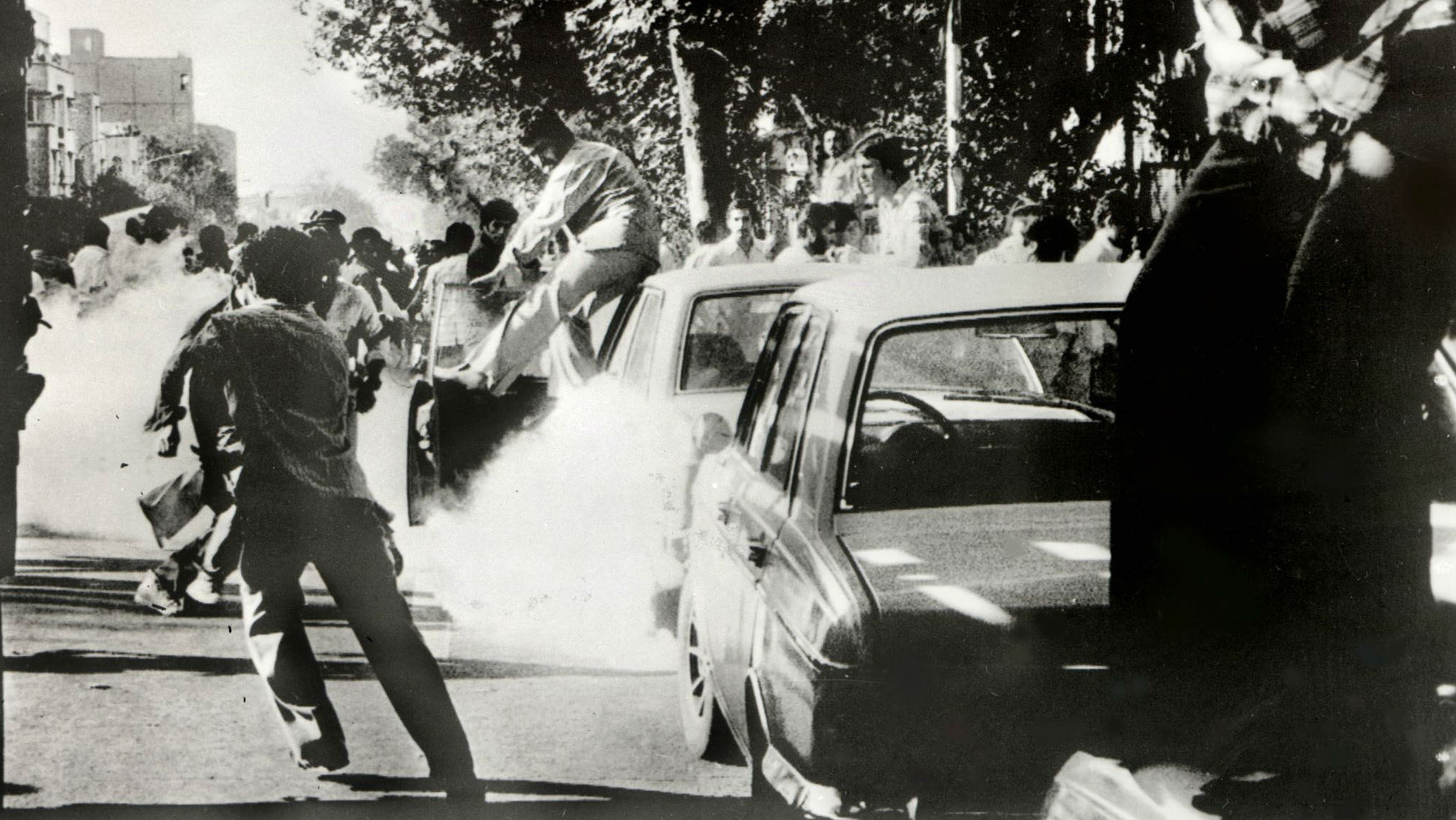

Just weeks earlier, millions of Iranians had protested in the streets as part of a popular movement against the regime led by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (also known as the Shah of Iran), which was seen as “brutal, corrupt and illegitimate”, Al Jazeera reports.

The protesters, who came from all social classes, eventually paved the way for the total overthrow of the Iranian royal family and the creation of the modern-day republic that now stands in its place.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“There was a feeling that we were being humiliated by the Shah and his regime. Domestically, the Shah’s regime was a dictatorship. There was no freedom,” said Mohsen Mirdamadi, an Iranian politician.

But the revolution came at a cost. The Shah had harboured close ties to the West, including the UK and US, both of which had helped overthrow a previous Iranian government in 1953 and greatly strengthened the executive power of the Shah.

The Independent reports that since the founding of Iran’s Muslim theocracy in 1979, its “relations with the outside world have deteriorated”, with former US president George W Bush famously declaring it part of the global “Axis of Evil” in 2002.

But officials within Iran have also grown intolerant of dissent in the wake of the revolution, and the paper adds that “those who endorse Western morals and values have been harassed, imprisoned and worse” by Iranian authorities.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So why did the Iranian Revolution happen, and how has it shaped modern geopolitics?

The 1953 coup

US and UK firms had “for decades controlled the region’s oil wealth” and had refused to relinquish power to neighbouring countries amid growing pressure to do so, says Foreign Policy. This prompted Iranian prime minister Muhammad Mossadegh to override the Western interests and nationalise Iran’s oil industry in 1951, to acclaim within the country.

In 1953, the British government and CIA responded by playing a “central role” in a dramatic coup d’etat that brought down Mossadegh and handed more executive power to the Western-friendly authoritarian Shah.

However, while the protection of Western oil interests was temporarily secured by the coup, a simmering “surge of nationalism” swept the country in the wake of the incident, which eventually boiled over in the late 1970s.

Economic downturn

In the wake of the coup, “extraordinary economic growth, heavy government spending, and a boom in oil prices led to high rates of inflation and the stagnation of Iranians’ buying power and standard of living”, explains Encyclopaedia Britannica.

However, by the start of the 1970s, the citizens’ economic difficulties were compounded by a dramatic increase in socio-political repression at the hands of the Shah’s regime. Most other political parties were marginalised or outlawed during this period, and “social and political protest was often met with censorship, surveillance, or harassment, and illegal detention and torture were common”, the encyclopedia adds.

The turning point, according to the Brookings Institution, came in the first half of 1977, when a group of journalists, intellectuals, lawyers and political activists published a series of open letters criticising the accumulation of power at the hands of the Shah. In the wake of these letters, the number of organised protests across Iran spiked significantly in 1978, with hundreds being killed in riots and their subsequent suppression by police.

The revolution

By mid-1978, Grand Ayatollah Khomeini, a prominent Islamic cleric and critic of the Shah who had been arrested and exiled by the monarchy in 1963, had amassed large support within Iran by recording speeches calling for a revolution from his home in the Paris suburbs.

“We were transmitting the imam’s messages, statements and speeches to Iran by telephone,” said reformist politician Seyed Ali Akhbar Mohtashamipur. “We had contacts in cities in Iran… They would record it and the next day they would be distributed in meetings, ceremonies, universities, mosques all over Iran,” said Al Jazeera.

By the end of 1978, protests against the Shah had turned into a revolution, and on 6 November 1978, he made an impromptu television broadcast to the nation in which he attempted to placate the protesters by suggesting he should take control of events and place himself at the head of this “revolutionary movement”.

History Extra says this was the final nail in the monarchy’s coffin. “Far from presenting a sense of strong leadership, the Shah appeared not only to waver but to also confirm that the country was indeed in the throes of a revolutionary upheaval,” the site says. “People who had hitherto been uncommitted now made preparations for the future. And that future did not include the Shah.”

On 16 January 1979, he fled the country, ending more than 2,000 years of Persian monarchy. Around two weeks later, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran to crowds of supporters and soon after appointed a hard-line Shia government.

The aftermath

The Asia Times says that Iran’s 1979 revolution was “such an all-encompassing movement that it influenced almost all aspects of life”.

“Shortly after the kingdom of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was toppled, revolutionary entities were established to take charge of emerging responsibilities in the new theocracy: revolutionary courts, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution,” the paper adds.

But the dust took years to settle and, to some observers, still has some way to go. A few months after the revolution, a group of pro-Khomeini activists stormed the US embassy in Iran in protest at Washington’s decision to grant the Shah asylum, preventing a potential trial for war crimes in Iran.

Meanwhile, 52 American citizens were famously held hostage in the embassy for 444 days in a siege that irrevocably damaged the relationship between Iran and its most powerful former ally and sparked diplomatic hostility that has lasted into the 21st century.

The Brookings Institution claims that the revolution did not directly benefit the poorer in society, or those who had felt neglected by the Shah’s regime. “Unlike the socialist revolutions of the last century, the Islamic Revolution of Iran did not identify itself with the working class or the peasantry, and did not bring a well-defined economic strategy to reorganise the economy,” the research group says.

Encyclopedia Britannica also suggests that, although the revolution had been a collaboration between the secular left and religious right, the Iran hostage crisis inadvertently allowed right-wing Khomeini supporters to “claim to be as anti-imperialist as the political left” and thus “ultimately gave them the ability to suppress most of the regime’s left-wing and moderate opponents”.

Nevertheless, the question of whether or not the revolution was a success does remain up for debate.

Mehmet Ozalp, an associate professor in Islamic studies, writes on The Conversation that, although the Iranian economy is currently in poor shape, with high unemployment rates, hyper-inflation and a bleak outlook from forecasters, the revolution “still stands” today.

“It has managed to survive four decades, including the eight-year Iran-Iraq war as well as decades of economic sanctions,” says Ozalp. “Comparatively, the Taliban’s attempt at establishing an Islamic state only lasted five years.”

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day