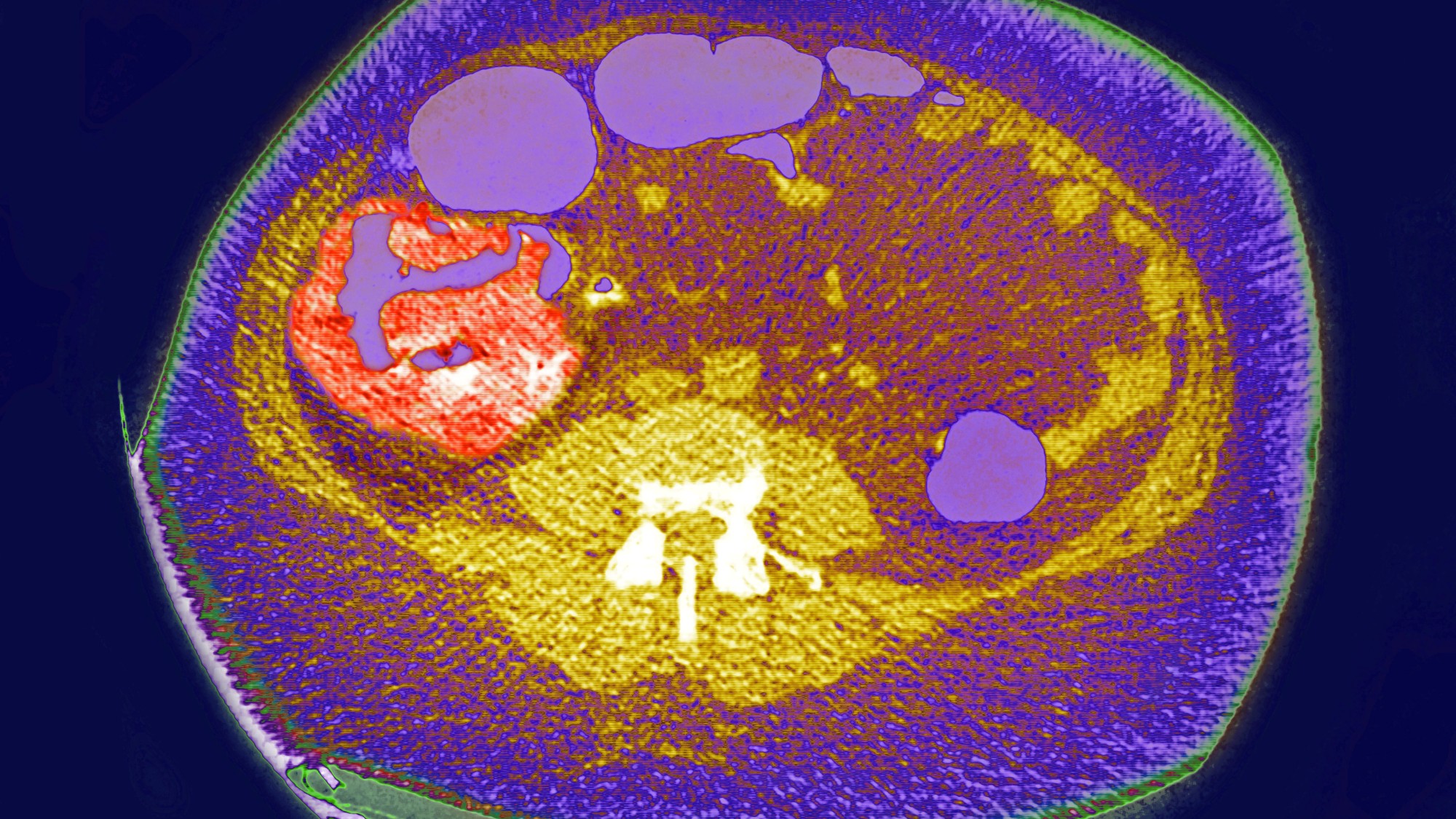

New drugs could make cancer a ‘manageable disease’ in ten years

New programme will target mutation of cells to offer ‘good quality of life’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cancer could become a “manageable disease” within the next 10 years, according to a top scientist.

A “Darwinian” programme of new drugs from the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) is designed to keep tumours in check and stop them being fatal.

The drugs will aim to stop cancer cells resisting treatment, allowing tumours to either be beaten completely or their growth limited to allow patients to live much longer. The team behind the drugs say they “open up the prospect of long-term control with a good quality of life”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Chemotherapy and other existing treatments sometimes fail because the deadliest cancer cells adapt and survive, causing the patient to relapse. Professor Workman of the ICR said: “Cancer's ability to adapt, evolve and become drug resistant was the cause of the vast majority of deaths from the disease and the biggest challenge we face in overcoming it.”

The Daily Mail describes the development as a “new dawn in the cancer war”. The Guardian says “the aim is to take the lethality out of cancer and turn it into a disease that… will no longer shorten or ruin lives”, while The Sun says cancer “could be ‘cured’ within a decade”.

Prof Workman said lab testing and clinical trials for the new medication would take around 10 years before it could potentially become available for patients. It will target a molecule called APOBEC, which is pivotal to the immune system, but is usurped in most cancers.

He said: “We firmly believe that, with further research, we can find ways to make cancer a manageable disease in the long term and one that is more often curable, so patients can live longer and with a better quality of life.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He added that there must also be a “culture change” so patients no longer worry if cancer cells remain. “We would like to take some of the fear away from advanced cancer, and hope patients will benefit from new approaches that may not always give them the ‘all clear’, but could keep cancer at bay for many years.”

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugs

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugsThe Explainer Antimicrobial resistance is causing millions of deaths. Could a faeces-filled pill change all that?

-

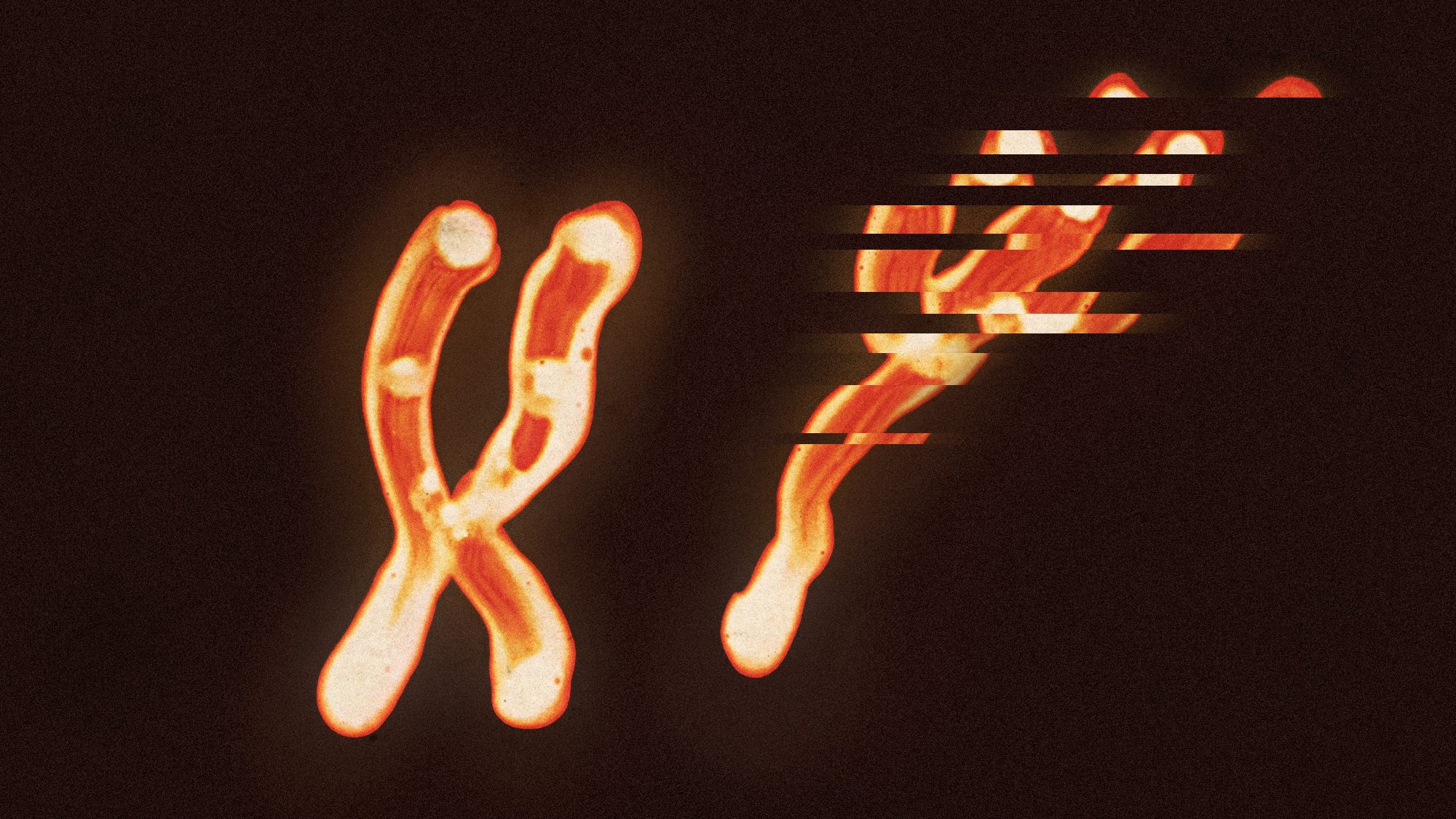

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for it

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for itUnder the radar The chromosome loss is linked to cancer and Alzheimer's

-

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young people

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young peopleUnder the radar Most exposure occurs in childhood

-

Why are more young people getting bowel cancer?

Why are more young people getting bowel cancer?The Explainer Alarming rise in bowel-cancer diagnoses in under-50s is puzzling scientists

-

Five medical breakthroughs of 2024

Five medical breakthroughs of 2024The Explainer The year's new discoveries for health conditions that affect millions