Zao: why Chinese face-swapping app is causing concern

Users asked to sign away the rights to their pictures

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A new Chinese face-swapping app has triggered fresh fears over online privacy.

Zao was released on Friday, and “quickly reached the top of the free charts on the Chinese iOS App Store”, reports The Verge. However, negative reviews about its privacy policy have flooded in almost equally as fast.

So why are users unhappy?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is Zao?

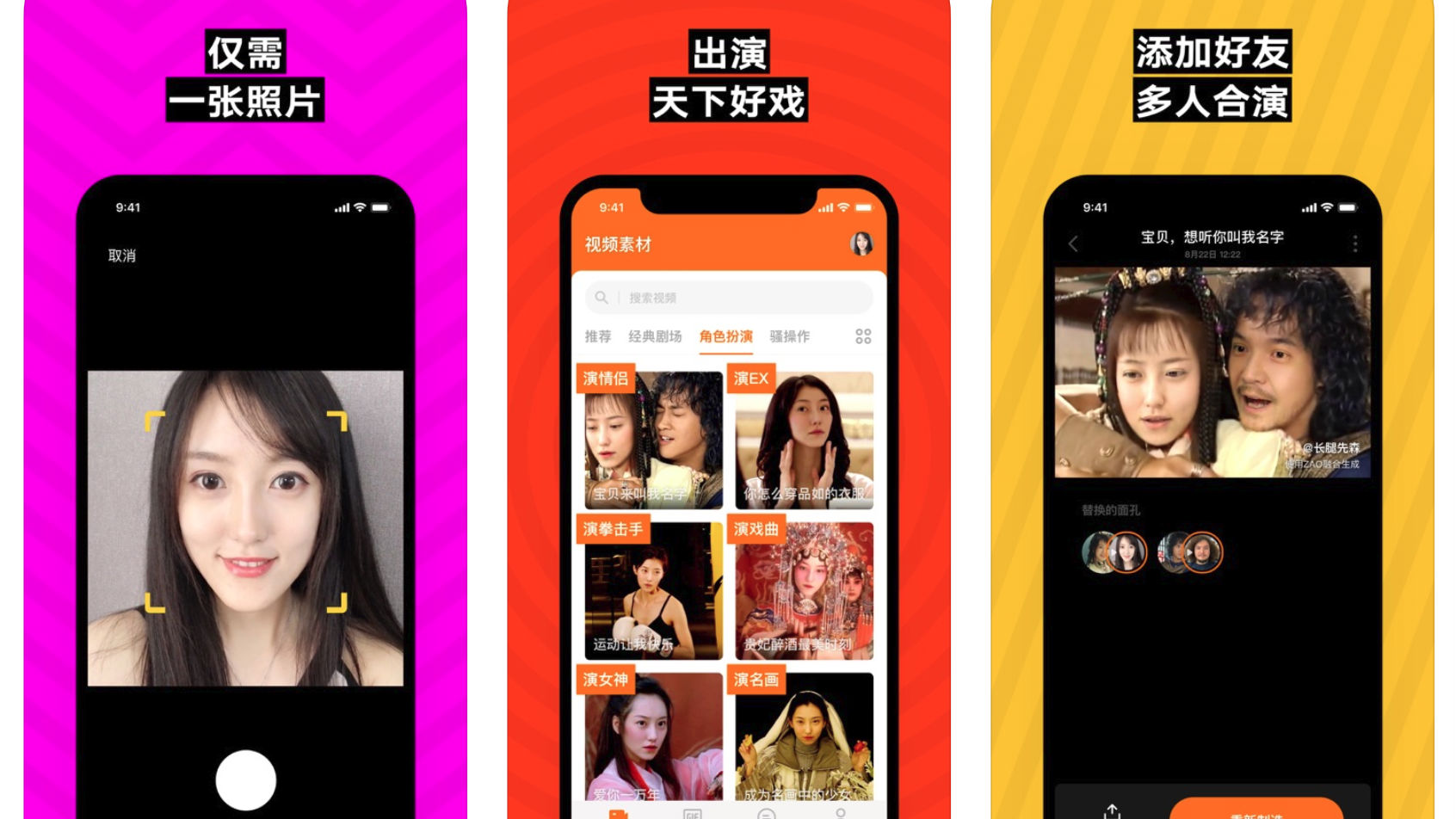

Users of Zao are able to replace the faces of actors, sports stars and other celebrities with their own in movie and TV clips.

The app uses “deepfake” technology that allows algorithms to create a video clip of a person based on just one picture of their face.

This technology is able to quickly register the parameters of both the user’s face and that of the person in the video, and to merge the two almost instantly.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“Such an approach is able to learn highly realistic and personalised talking head models of new people and even portrait paintings,” according to a paper by researchers at New York’s Cornell University.

Why are users concerned?

The app requires users to grant the developers unlimited rights over the pictures they upload - allowing the app makers to collect free data to use however they want, says Forbes.

The user agreement says anyone who uploads pictures of themselves is surrendering the intellectual property rights to images of their face.

The company insists the images will only be used for marketing purposes, but users are worried their data may not be safe with a company that has a poor track record on privacy.

Zao is published by Momo Inc, which previously came under fire in December 2018 when a package containing the phone numbers and account passwords of 30 million users of China’s Momo dating app was put up for sale on the dark web.

There are also wider concerns that deepfakes can mislead people into believing fake videos are real.

“At the most basic level, deepfakes are lies disguised to look like truth,” says Andrea Hickerson, director of the school of communication at the University of South Carolina.

“If we take them as truth or evidence, we can easily make false conclusions with potentially disastrous consequences.”

Indeed, “deepfakes put companies, individuals, and the government at increased risk”, says science and tech magazine Popular Mechanics.

On Monday, chat messenger WeChat blocked content shared by Zao over “security risks” and widespread user backlash, reports TechNode.

A statement posted on Chinese social networking site Weibo by Zao said: “We thoroughly understand the anxiety people have towards privacy concerns.

“We have received the questions you have sent us. We will correct the areas we have not considered and require some time.”

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar