Modernising modern art

Modern art, a key art movement, is undergoing a revamp

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sotheby’s held its third annual “Modernités” sale in Paris last week, alongside the International Contemporary Art Fair (FIAC). The sale included Medea (1929) by Francis Picabia. With a nod to Sandro Botticelli, Picabia depicts the semi-divine enchantress from Greek mythology who goes on to marry Jason, the leader of the Argonauts. It was valued at up to €2m.

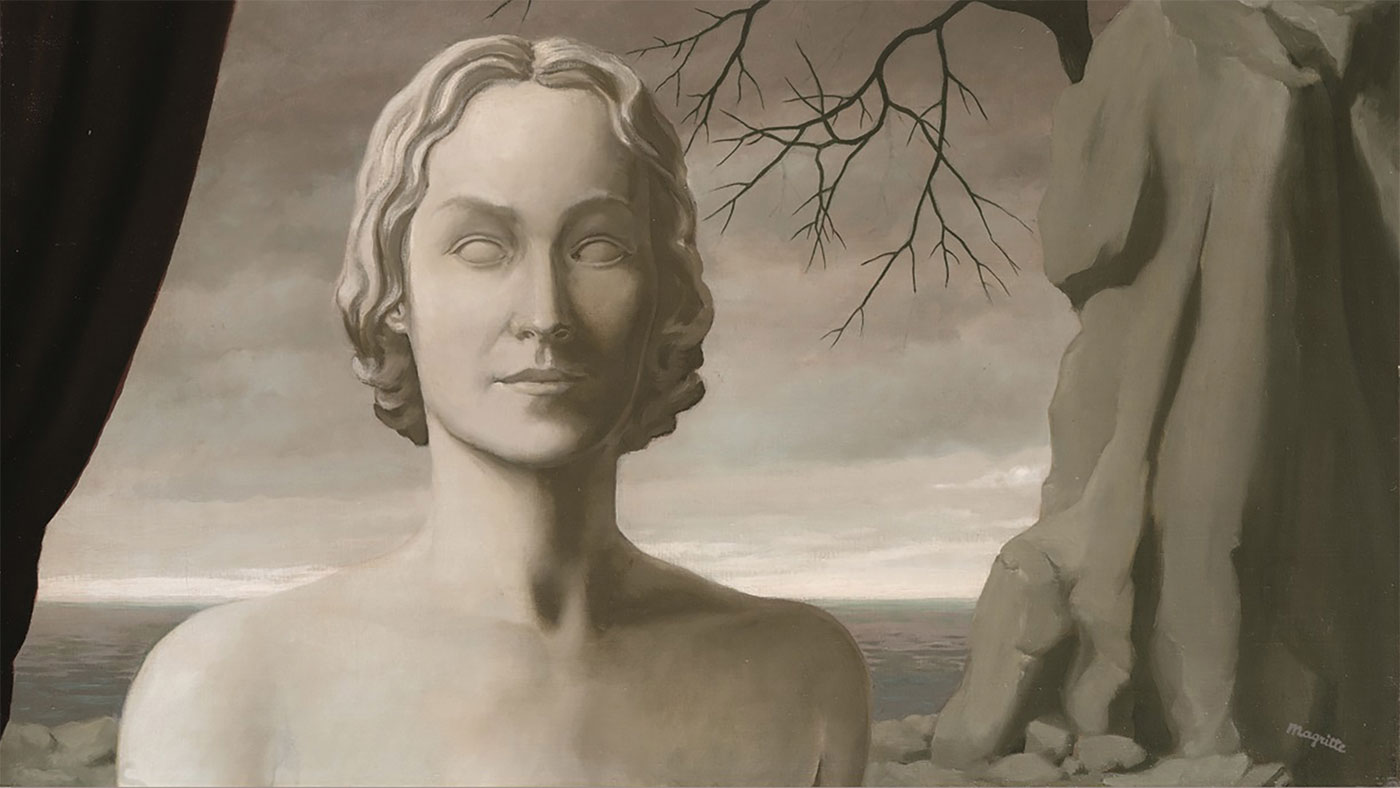

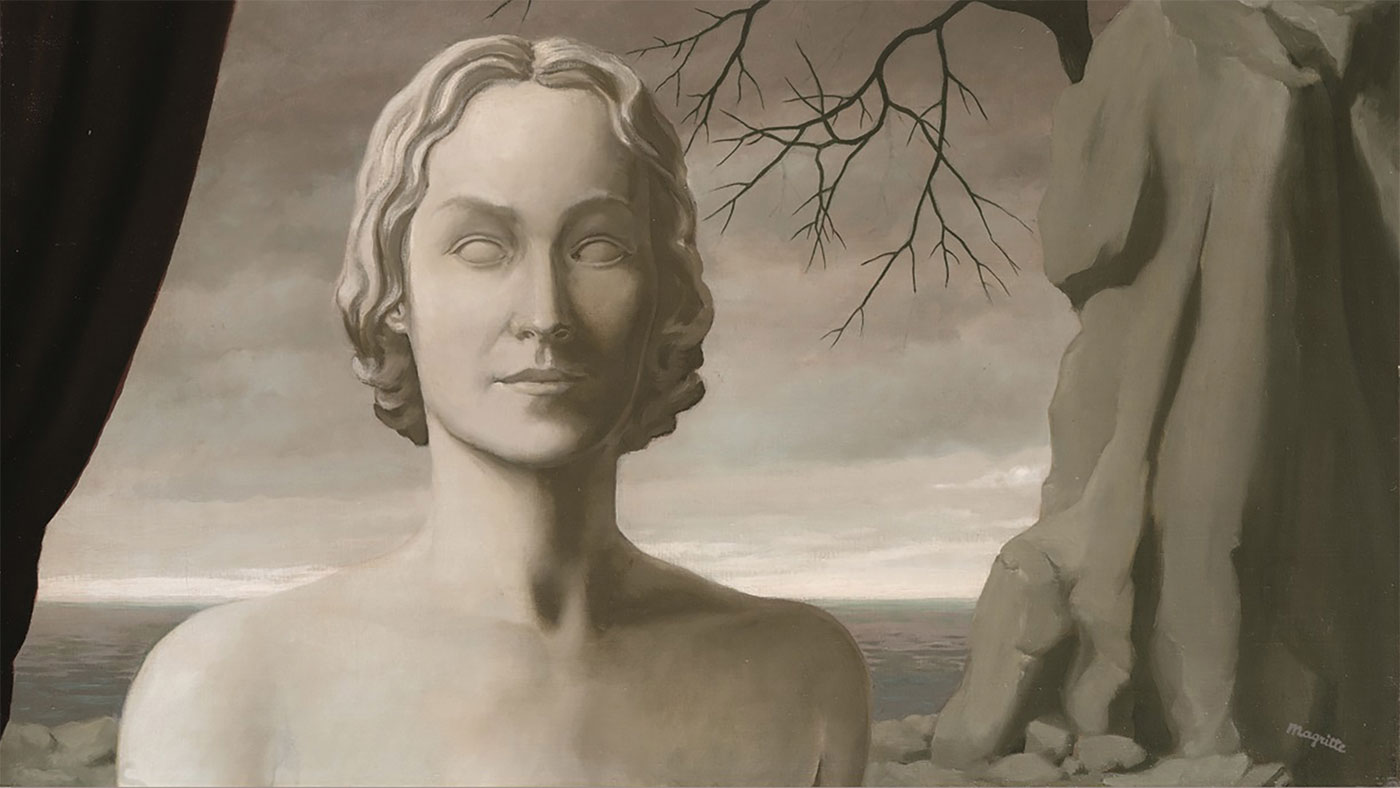

There was also a large painting by Marc Chagall entitled Le Cirque Mauve (1966) and valued at up to €5m, along with René Magritte’s L’Incorruptible (1940 – pictured below), showing the Belgian surrealist’s wife, Georgette, as a statue before a bleak landscape. It was on sale for €1.5m. The event was concerned with “defining modernity”, as Sotheby’s put it. But that is easier said than done.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Rebooting modern art

Modern art begin in the 1880s, more or less – some say ten, 20 years earlier. Either way, its concerns “now feel long ago, forged in a time of rapid industrial change”, says Jerry Saltz on New York Magazine’s Vulture website. Time for a reboot, then. Modernism shapes “the ways we see the world, and how the world sees itself”, he says.

But recently, “seismic shifts have occurred” that have stretched the boundaries of the art movement to its limits. Modernism needs to be made modern again. That is something the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York has been wrestling with for a long time.

Now, after a $450m overhaul, the gallery is reopening on 21 October as a “living, breathing 21st-century institution, rather than the monument to an obsolete history – white, male and nationalist” – that it had become since it was founded in 1929, according to Holland Cotter in The New York Times. (MOMA first opened just nine days after the Wall Street Crash. Let’s hope its October reopening this time is less eventful.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

MOMA has long been known for the strict arrangement of its displays along the lines of an “ironclad view of modern art as a succession of ‘isms’ (Cubism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism)”, says Cotter, But now it is attempting to reinvent itself without hurting its appeal. The result is a sort of “Modernism Plus, with globalism and African-American art added”.

On Thursday a preview of the museum’s new layout showcased the museum’s 47,000 square feet of new gallery space and the “radical ‘remix’” of its permanent collection, says Miranda Bryant in The Guardian. Now, for example, Pablo Picasso’s 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon can be found close to Faith Ringgold’s 1967 work American People Series #20: Die, depicting a scene from a race riot.

That’s because, in today’s digital world, we consume a wide variety of images that are out of context and outside of traditional settings, as MOMA’s director, Glenn Lowry, tells Bryant. “It reframes Picasso differently,” he says. “It doesn’t diminish Picasso, it simply means that there’s another conversation you can have around Picasso.”

Spiritual modern artists

Modern art has its roots in the late 19th century, when spiritualism was flourishing, says Caroline Marciniak in Frieze Masters Magazine. It was also an era of profound technological and socio-economic change. “Railways were vastly extended, suburbs sprouted factories and cities towered upwards.”

But with technological progress came disillusionment, and “a sense of longing and decay”. Impressionism was too “formal, based on fleeting sensory impressions and grounded in everyday life”, says Marciniak. “The renewed interest in occultism was driven by a search for alternatives and origins, for a world that holds both chaos and coherence… its rhythms hinting at key truths.”

“At the turn of the century, modern artists and Modernists were all into versions of spiritualism,” The Gallery of Everything’s James Brett told the BBC’s Kelly Grovier. “So spiritual art had a huge impact on what became Modernism and therefore art today.”

The evidence is in the diversity of visions on display at The Gallery’s The Medium’s Medium exhibition, says Grovier. From the “haunting Surrealism” of Marian Spore Bush to the portraits of the German artist Margarethe Held, who believed she was instructed by the Hindu god Shiva, the artworks demonstrate “just how far and wide the mystical impulse pulsated”. (The Gallery of Everything, 4 Chiltern Street, London – until 24 November.)

This article was originally published in MoneyWeek

-

The cabbage comeback

The cabbage comebackThe Week Recommends Gone are the days of ‘WWII boiled cabbage recipes’. The humble vegetable is enjoying a resurgence

-

Fine food on a budget

Fine food on a budgetThe Week Recommends Excellent value eateries with the Michelin inspectors’ seal of approval

-

Where to go for the 2027 total solar eclipse

Where to go for the 2027 total solar eclipseThe Week Recommends Look to the skies in Egypt, Spain and Morocco